Chief Complaint: Acute right eye pain

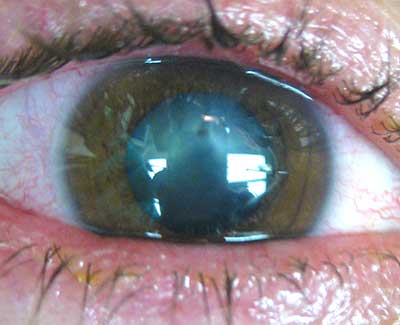

History of Present Illness: A 36-year-old male presented with right eye pain immediately after he had been pounding a metal object with a metal chisel. He was not wearing safety glasses and felt something strike his right eye. This was followed by tearing and blurred vision. He continued working for a few hours, but when the vision and tearing did not improve he went to a local emergency room. He was diagnosed with a corneal abrasion and sent home on topical antibiotics. An appointment with a local ophthalmologist was made for the following morning where his vision was found to be hand motions, a traumatic cataract had developed, and there was suspicion of an intraocular foreign body (IOFB). He was then referred emergently to the University of Iowa Ophthalmology On Call Service.

Past Ocular History: The patient had no previous eye trauma, disease, or surgery.

Medical History: Unremarkable

Medications: Moxifloxacin eye drops

Family and Social History: Noncontributory

Review of Systems: Negative

|

|---|

Visual acuity:

Intraocular pressure:

Pupils: Dilated upon arrival by outside ophthalmologist

External and anterior segment examination (see Figure 1A):

Dilated fundus exam (DFE):

Since there was no view to the posterior pole and we suspected an IOFB due to the presence of the cataract and the mechanism of injury, the patient underwent echography of the right globe. (See Figure 2A.)

CLINICAL COURSE:

The patient was diagnosed with a corneal laceration, traumatic cataract, and a metallic IOFB. He was brought to the operating room urgently for corneal laceration repair, pars plana vitrectomy, lensectomy, and removal of the metallic IOFB. Prior to surgical repair, the patient received one dose of intravenous antibiotics (cefazolin 1000 mg and vancomycin 1250 mg) and had his tetanus shot updated.

Video: Intraocular Foreign Body. If video fails to load, please use this link: https://vimeo.com/258087704

Creating a water-tight globe was the first priority, which was accomplished by closing the corneal laceration with 2 10-0 nylon sutures (see Figure 3A). A peritomy was performed, followed by scleral incisions for 20-gauge vitrectomy. Using the vitrector, the cataract and posterior capsule were removed with care to preserve the anterior capsule for future intraocular lens placement. A core and peripheral vitrectomy were then performed. The retina was then examined and a metallic object with a surrounding inflammatory capsule was found embedded in the retina, temporal to the macula. Laser demarcation of the retina surrounding the metallic IOFB was performed using an endolaser. An intraocular rare earth magnet was inserted into the eye and used to engage and lift the IOFB anteriorly into the vitreous cavity (see Figure 3B). Forceps were then inserted to grab the IOFB from the magnet and remove it from the eye. A careful indented peripheral retinal examination was performed, which did not reveal any other retinal breaks or impact sites. The scleral and conjunctival incisions were closed with 7-0 Vicryl suture. Fifty mg of cefazolin and 10 mg of dexamethasone were injected beneath the conjunctiva.

Post-operatively the patient was instructed to use scopolamine twice daily and tobramycin-dexamethasone ointment 4 times daily in the operative eye. At the first post-operative week, vision in the right eye had improved to 20/60-1 with a +10.00 diopter (D) lens. At his 8 week follow-up, the patient's vision improved to 20/25-3 with a +10.0D lens.

He is to undergo secondary intraocular lens placement after all inflammation has subsided and his corneal stitches are removed. Until his secondary intraocular lens is placed, he will continue to wear a +13.00D contact lens in this aphakic right eye.

This case illustrates the stereotypical history for a metallic IOFB--a young male who is hammering or chiseling metal on metal and feels something strike the eye. Based on the history alone, the possibility of an IOFB should be thoroughly investigated, or the diagnosis can easily be missed due to the sometimes underwhelming external clinical appearance. Although he was evaluated in the emergency room on the day of his injury, this patient did not undergo a dilated exam, an ophthalmologist was not consulted the day of his injury, nor did he have any imaging to evaluate for the possibility of an IOFB. He was diagnosed with a corneal abrasion and no further work-up was done. The possibility of IOFB was not considered until the follow up visit with an ophthalmologist more than 16 hours after the injury. This delay in diagnosis can lead to a worse prognosis depending upon the location of the IOFB and the development of assocated endophthalmitis, particularly if the IOFB is organic material or if the injury is sustained in a rural environment (Boldt 1989).

Epidemiology: Foreign bodies are one of the most common causes for ophthalmologic emergencies, which represent 3% of all United States emergency room visits (Babineau 2008). Risk factors include being male, not wearing eye protection, and performing a metal-on-metal task (hammering or chiseling a metal object) (Ehlers 2008, Babar, 2007, Napora 2009). The mean age at which injury occurred was 33 years. The foreign body most frequently enters the cornea, and approximately 65% of them land in the posterior segment (Ehlers 2008).

Treatment: Treatment depends on the location and scope of the injury but usually involves emergent removal of the IOFB with repair of any damaged structures. This may involve an anterior approach if the IOFB is located in the anterior chamber and may include corneal laceration repair, lensectomy, and/or anterior vitrectomy. A very careful retinal examination must be performed to identify an IOFB, the impact site of the IOFB, the presence of multiple IOFBs, and any other retinal damage including tears or detachments that may have occurred. If visualization of the retina is not possible due to a cataract or vitreous hemorrhage, imaging via a CT of the orbits or ultrasound of the globe is essential to evaluate for an IOFB. If the posterior segment is involved, a pars plana approach is utilized. The IOFB can be removed (if metallic) using an external or internal magnet or forceps. Typically, a pars plana vitrectomy is also performed. If a retinal tear or detachment is identified it is often repaired at the time of IOFB removal. If the IOFB is organic, or if the injury occurs in a rural setting, one may choose to culture the vitreous and IOFB and inject intravitreal antibiotics at the time of surgery as well.

Complications: One of the most common complications of an IOFB is a retinal detachment (14-26%). Other complications include: endophthalmitis (4-6%), corneal scar, cataract, angle recession glaucoma, vitreous hemorrhage, retained IOFB, blind/painful eye, and sympathetic ophthalmia (Ehlers 2008).

Prognostic factors: Patients with smaller wound lengths (under 2mm), IOFBs that are located in the anterior segment only, and those with a normal lens at presentation have the best prognosis. Negative prognostic factors include a longer wound length (greater than 3.5mm), posterior segment IOFB, poor initial visual acuity, and the presence of complications arising from IOFB (retinal detachment, endophthalmitis) (Ehlers 2008, Bai 2010, Unver 2009).

Endophthalmitis: Endophthalmitis is a concern with any type of IOFB. If the foreign body contains organic matter, intravitreal injection of gentamycin and either vancomycin or clindamycin was previously suggested (Boldt 1989); however, the use of ceftazidime has now largely replaced that of gentamycin in order to avoid aminogylcoside toxicity. Foreign bodies that result from metal-on-metal activity are less likely to contain organic material or bacterial contamination. In theory, the heat of the object as well as the anti-bacterial nature of ionized metals makes it difficult for bacteria to survive. It is still reasonable, however, to culture and treat with intravitreal antibiotic injections at the conclusion of the surgery.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT

|

Babar TF, Khan MT, Marwat MZ, Shah SA, Murad Y, Khan MD. Patterns of ocular trauma. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2007;17(3):148-153. https://PubMed.gov/17374300. DOI: 03.2007/JCPSP.148153

Babineau MR, Sanchez LD. Ophthalmologic procedures in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2008;26(1):17-34, v-vi. https://PubMed.gov/18249255. DOI: 10.1016/j.emc.2007.11.003

Bai HQ, Yao L, Meng XX, Wang YX, Wang DB. Visual outcome following intraocular foreign bodies: a retrospective review of 5-year clinical experience. Eur J Ophthalmol 2011;21(1):98-103. https://PubMed.gov/20544679

Boldt HC, Pulido JS, Blodi CF, Folk JC, Weingeist TA. Rural endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology 1989;96(12):1722-1726. https://PubMed.gov/2622617

Ehlers JP, Kunimoto DY, Ittoop S, Maguire JI, Ho AC, Regillo CD. Metallic intraocular foreign bodies: characteristics, interventions, and prognostic factors for visual outcome and globe survival. Am J Ophthalmol 2008;146(3):427-433. https://PubMed.gov/18614135. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.05.021

Napora KJ, Obuchowska I, Sidorowicz A, Mariak Z. [Intraocular and intraorbital foreign bodies characteristics in patients with penetrating ocular injury]. Klin Oczna 2009;111(10-12):307-312. https://PubMed.gov/20169884

Unver YB, Acar N, Kapran Z, Altan T. Prognostic factors in severely traumatized eyes with posterior segment involvement. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2009;15(3):271-276. https://PubMed.gov/19562551

Bouraoui R, Bouladi M, Mghaieth F, Chaker N, Sammouda T, El Matri L. A metallic intraocular foreign body discovered 26 years after ocular injury. Tunis Med 2016;94(3):245-246. https://PubMed.gov/27575512

Bypareddy R, Sagar P, Chawla R, Temkar S. Intraocular metallic foreign body causing branch retinal vein occlusion. BMJ Case Rep 2016;2016. https://PubMed.gov/26994054. DOI: 10.1136/bcr-2016-214745

Ishii K, Nakanishi M, Akimoto M. Removal of intracameral metallic foreign body by encapsulation with an intraocular lens injector. J Cataract Refract Surg 2015;41(12):2605-2608. https://PubMed.gov/26796440. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2015.10.046

Lawrence DA, Lipman AT, Gupta SK, Nacey NC. Undetected intraocular metallic foreign body causing hyphema in a patient undergoing MRI: a rare occurrence demonstrating the limitations of pre-MRI safety screening. Magn Reson Imaging 2015;33(3):358-361. https://PubMed.gov/25523608. DOI: 10.1016/j.mri.2014.12.009

Sindal MD, Sengupta S, Vasavada D, Balamurugan S. Retained intraocular iron foreign body presenting with acute retinal necrosis. Indian J Ophthalmol 2017;65(10):1036-1038. https://PubMed.gov/29044081. DOI: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_363_17

Abrams P, Birkholz ES, Tarantola RM, Oetting TA, Russell SR. Intraocular Foreign Body: A Classic Case of Metal on Metal Eye Injury. EyeRounds.org. May 24, 2011; Available from: https://eyerounds.org/cases/132-intraocular-foreign-body.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.