INITIAL PRESENTATION

Chief Complaint: Blurred vision in the right eye

History of Present Illness:

A 22- year-old white man with a history of asthma, vitamin D deficiency, and blepharitis presented to the cornea clinic with gradual onset blurred vision in the right eye and photophobia over 6 weeks.

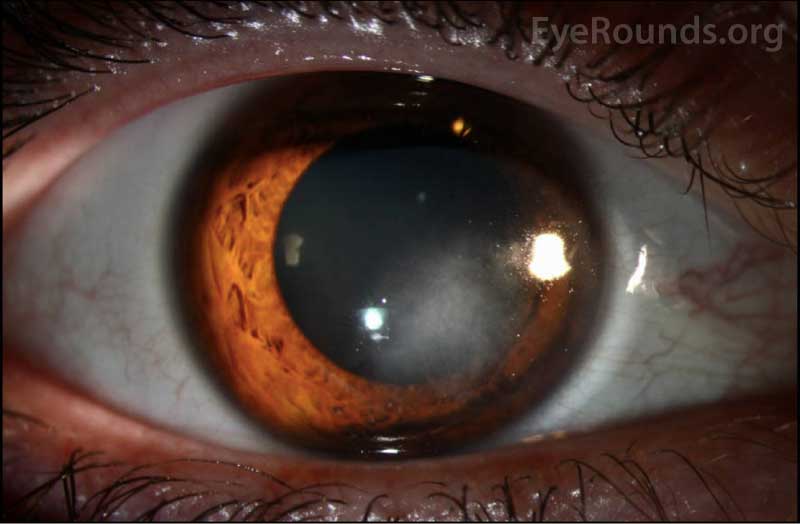

The patient first presented to his local ophthalmologist with this complaint and at that time, his vision was 20/30+2 in the right eye (OD) and 20/25 in the left eye (OS). Examination of his right eye revealed posterior corneal stromal haze with stromal neovascularization extending from the limbus which measured 5.2 mm from the limbus and 5.5mm in width. Fine white keratic precipitates were also observed at the edges of the haze. The remainder of his exam, including the posterior segment, was unremarkable. He was started on topical prednisolone acetate (1%) every hour and valacyclovir 1 gram by mouth three times a day for treatment of possible herpes simplex virus (HSV stromal) keratitis. Laboratory tests were also conducted to rule out syphilis, tuberculosis, Lyme disease, and sarcoidosis.

He was referred to the Cornea Clinic at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics for further evaluation and management. At initial presentation to us, the patient reported improvement in vision and photophobia but he had not returned to his baseline.

He denied history of contact lens use, known exposure to foreign material, recent swimming or travel, cold sores or shingles, joint pain, sexually transmitted diseases, hearing loss, fever, recent travel, or insect bites.

Past Ocular History:

Past Medical History:

Medications:

Allergies:

Family History: :

Social History:

Review of Systems: :

OCULAR EXAMINATION

Interstitial keratitis secondary to:

CLINICAL COURSE

His history and exam were consistent with interstitial keratitis. His positive response to topical steroids and antiviral medication, along with lab results negative for other common causes of interstitial keratitis (syphilis, tuberculosis, Lyme disease, sarcoidosis), suggested a herpetic cause for the stromal inflammation. He had no history of shingles (VZV). HSV was thought the most likely etiology.

Topical prednisolone was continued every 2 hours until control of active inflammation had been achieved. This was followed by a slow taper, with the regimen guided by the following principles: (1) to not decrease frequency by more than 50% at any one time, and (2) to ensure that the same degree of control over inflammation is maintained with each reduction. Oral antivirals were continued at the treatment dose for HSV (valacyclovir 500mg TID) and later decreased to the maintenance dose. Additional details on management of HSV stromal keratitis can be found at this EyeRounds link (https://eyerounds.org/cases/160-HSV.htm). Over the next several visits, the patient noted a significant improvement in vision, pain, and photophobia.

DIAGNOSIS: Interstitial keratitis secondary to HSV

DISCUSSION

Etiology/Epidemiology:

Interstitial keratitis is a non-ulcerating inflammatory reaction of the corneal stroma that is characterized by non-suppurative infiltration and often stromal vascularization. The epithelium and endothelium are not affected (1). Scarring due to stromal inflammation and vascularization in interstitial keratitis can result in decreased vision.

Interstitial keratitis (IK) is a common endpoint of any keratitis that predominantly involves the corneal stroma. Therefore, there are many potential etiologies of IK that can be broadly categorized into immune-mediated or infectious causes (1). Immune-mediated etiologies include Cogan syndrome, sarcoidosis, and Mycosis fungoides. Infectious etiologies can be bacterial, viral, or protozoal in nature (1). Bacterial causes include syphilis, Lyme disease, tuberculosis, leprosy, brucellosis, and leptospirosis. Viral causes include Herpes simplex (HSV), Herpes zoster (VZV), Epstein-Barr (EBV), mumps, rubella (measles), influenza, and vaccinia. Parasitic causes include leishmaniasis, onchocerciasis, and trypanosomiasis (1, 2).

In the United States the most common etiologies are HSV and congenital syphilis (1, 2). Other causes are rare and can often be distinguished based on concurrent medical or ocular history and review of systems.

HSV is a double-stranded DNA virus with two main serotypes, HSV-1 and HSV-2. HSV-1 is commonly associated with infections of the face (cold sores) and upper body, whereas HSV-2 is more commonly associated with genital infections and infections of the lower half of the body (3). Although both serotypes can cause ocular disease, the vast majority of ocular HSV is attributed to HSV-1 (4). HSV-1 infections are highly prevalent (47.8% among individuals aged 14 to 49 years) (5) and can often occur even in the absence of patients recalling symptoms such as cold sores.

Ocular HSV infection can involve many sites in and around the eye including the eyelids, conjunctiva, cornea, iris, uveal tract, trabecular meshwork, optic nerve and retina. Common presentations of ocular HSV infection include blepharitis, follicular conjunctivitis, keratitis, and keratouveitis (6). HSV keratitis can be further categorized into epithelial keratitis (dendritic and geographic) (7, 8), stromal keratitis (interstitial and necrotizing) (9), and endothelial keratitis (disciform) (6, 10). Stromal keratitis, usually in the interstitial form, occurs in 2% of initial episodes and 20-48% of recurrent episodes of ocular HSV disease (11).

Pathophysiology:

The main route of HSV transmission is by direct contact of the virus with a host’s mucous membranes or skin (12). Once the host is infected, the virus may spread to the trigeminal ganglion by retrograde axonal transport along sensory nerves (4, 13) and may enter ocular cells through specific glycoproteins on the ocular cell surface (14, 15). Viral replication takes place at the trigeminal ganglion until it is driven into latency by CD8+ T-cell activity or inefficient viral DNA repair (4). Reactivation of the virus from latency can cause a recurrent episode of HSV and can be triggered by several factors such as stress, UV radiation, or fever (4). HSV infection of the corneal nerves can cause neurotrophic disease over time, which is characterized by decreased corneal sensation due to damage to corneal sensory fibers (16). It is has been hypothesized that a combination of events, including an increase in pro-inflammatory factors (i.e. IL-6) triggered by HSV infection, may contribute to corneal nerve loss (16).

Ocular HSV infections can occur when a patient is first exposed to the virus or from a reactivation of the virus in an already infected individual (3). HSV stromal keratitis most often occurs in the setting of recurrent HSV disease (4). The morbidity associated with stromal keratitis is thought to be secondary to CD4+ T-cell destruction during the inflammatory response to the virus or to viral antigens persistent in the corneal stroma after infection (13, 17). HSV stromal keratitis is most commonly interstitial and is caused by the antibody-complement cascade against retained viral antigens in the stroma, or necrotizing, which is caused by live viral proliferation within the stroma (10).

Signs/Symptoms:

A comprehensive medical and ophthalmic history, review of systems, slit lamp and dilated fundus examination, and targeted laboratory testing is important in diagnosing interstitial keratitis and its etiology (2). During the medical history and review of systems, questions should be asked regarding history of recent travel, insect bites, animal exposure, contact lens use, recent swimming in fresh water, sexually transmitted disease, trauma, and symptoms such as hearing loss or shortness of breath (18). Individuals with HSV keratitis may have a history of prior HSV keratitis, immunodeficiency, or triggering event such as recent illness (19). However, many patients with IK secondary to HSV are otherwise healthy and do not recall prior oral or labial herpes or prior keratitis.

In the acute setting, IK usually presents with mid to deep stromal WBC infiltration and neovascularization. In IK secondary to HSV, the inflammation is usually unilateral, can be diffuse or sectoral, and is often associated with decreased corneal sensation (2, 3, 19). HSV may concurrently affect other corneal layers, including the epithelium (dendritic lesions) or endothelium and anterior chamber (keratic precipitates, iritis, elevated intraocular pressure). Though rare, HSV can affect the posterior pole with potentially devastating visual consequences. Thus, a dilated exam is necessary to rule out acute retinal necrosis (ARN) or progressive acute retinal necrosis (PORN). In the chronic phase, IK may result in permanent stromal scarring, haze, and lipid deposition. Neovascularization may regress to form ghost vessels.

The appearance of IK can be similar despite numerous possible etiologies. As discussed above, obtaining a thorough medical history and review of systems can often assist with diagnosis. One distinguishing exam finding worth noting is that IK secondary to congenital syphilis is usually bilateral and may have prominent neovascularization, resulting in the so-called “salmon patch” appearance. Onset of presentation is usually in adolescence and is associated with decreased vision and severe photophobia. IK may be the sole finding of congenital syphilis, although there may other stigmata such as misshapen “peg” teeth, or neonatal complications such as rhinorrhea, jaundice, and aseptic meningitis.

Testing/Laboratory work-up:

Interstitial keratitis secondary to HSV is largely a clinical diagnosis. In addition to the slit-lamp examination, Cochet-Bonnet esthesiometry should be used to measure corneal sensation as diminished corneal sensitivity is a distinguishing characteristic (1).

It is important to note that laboratory tests based on corneal scrapings (Giemsa stain, Tzanck smear, viral culture, PCR/ELIZA testing) are diagnostic only when live virus is present, such as in HSV epithelial keratitis (1, 19). They are not useful in the diagnosis of HSV stromal keratitis, in which clinical findings are the result of immunologic reactions triggered by prior infections.

Serum HSV antibody testing can be of some utility. A negative result indicates that the patient has never been infected with HSV, or that the infection occurred very recently (within a few months). A positive result indicates infection with HSV at some point in the past. Since about 70% of adults have HSV-1 serum antibodies, a positive result is not necessarily helpful in determining whether findings of interstitial keratitis are secondary to HSV. However, a negative HSV serum antibody test may help rule it out.

In patients that lack common signs for HSV interstitial keratitis, laboratory testing for non-herpetic etiologies of interstitial keratitis may need to be considered (17). Bacterial and fungal cultures, along with confocal microscopy, can be used to rule out infectious causes of interstitial keratitis. We also have a low threshold for testing patients for syphilis given the ease and non-invasive nature of testing and the profound impact of systemic treatment.

Treatment/Management:

The two primary goals in the management of HSV interstitial keratitis is to control local corneal inflammation and to treat the underlying systemic viral disease to reduce the risk of recurrent disease (18).

Topical corticosteroids, such as prednisolone acetate 1%, are used to control corneal inflammation and to alleviate the acute symptoms of pain, discomfort, and blurred vision while reducing scarring and neovascularization (18, 20). As the corneal inflammation decreases, steroids are tapered slowly but may be required chronically (1) to prevent recurrence. Oral antivirals such as acyclovir and valacyclovir are commonly given in conjunction with topical corticosteroids, not to treat live viral infection, but to reduce risk of viral reactivation with concomitant topical steroid use (17, 18, 21). Oral antivirals are preferred to topical antivirals as topical antivirals, such as trifluridine solution and ganciclovir ophthalmic gel, have been observed to be inadequate in penetrating the corneal stroma (22). Furthermore, long-term use of some topical antivirals, such as trifluridine solution, have been observed to have toxic effects on the ocular surface (22). In the past, antivirals were given alone to treat HSV interstitial keraitis. Clinical trials, such as the Herpetic Eye Disease Study (HEDS), have reported that antivirals given in conjunction with corticosteroids result in reduced persistence and progression of disease, promote faster recovery (23), and increase likelihood of visual improvement at 6 months (24).

In general, given the high benefit-to-risk ratio associated with oral antiviral therapy, we recommend prophylactic oral antivirals (acyclovir 400mg BID or valacyclovir 500mg daily) long term after an episode of HSV interstitial keratitis. Prophylaxis has been shown to effectively reduce the incidence of recurrent stromal keratitis (23) as well as recurrent orofacial disease(25).

EPIDEMIOLOGY OR ETIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

|

References

Wole B., Diel RJ, Stiff HA, Kardon RH. Horner syndrome due to ipsilateral internal carotid artery dissection. EyeRounds.org. Posted February 23, 2021. Available from http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/300-miller-fisher-syndrome.htm.

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.