Chief Complaint: Non-specific "blurriness" of vision, left eye (OS).

History of presenting illness: 44-yo female with no previous ocular history presents after a 9 day history of non-specific blurred vision in the left eye. This "graying out" quality is painless and not associated with any known infection nor precipitating factor nor other ocular symptoms. There were no associated systemic symptoms (including no parasthesias, numbness, weakness, nor ataxia). Over several days the vision steadily dropped. The patient first went to her family doctor four days after symptoms began and was referred to her local ophthalmologist. After examination, a single 80 mg dose of prednisone was administered. There were no special studies locally, and the patient was referred to the University of Iowa for consulation thereafter.

Ocular History: No previous ocular history. No eye surgery, trauma, nor contact lens use.

Medical History: Gallbladder surgery, ileus, and borderline high blood pressure. Review of systems negative.

Family History: Cataract, glaucoma, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, and renal disease.

Social History: Patient works as a nurse. She has no tobacco nor alcohol use.

EXAM OCULAR

|

|

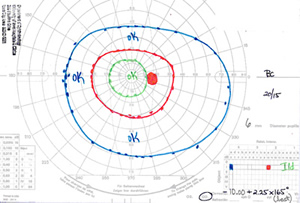

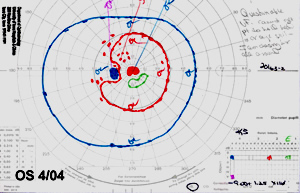

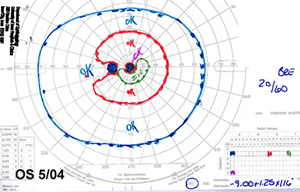

| 1A: GVF, OS reveals a large cecocentral scotoma. | 1B: GVF, OD is essentially normal. |

| 2A: Stereo photos, OD. | |

|

|

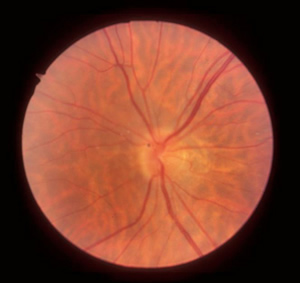

| 2B: Stereo photos, OS. No vitreous cell, sectoral disc edema temporally. | |

|

|

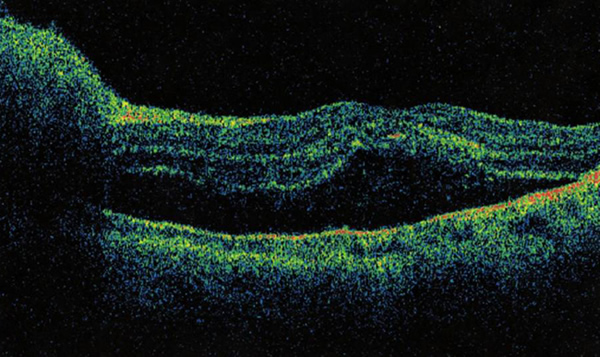

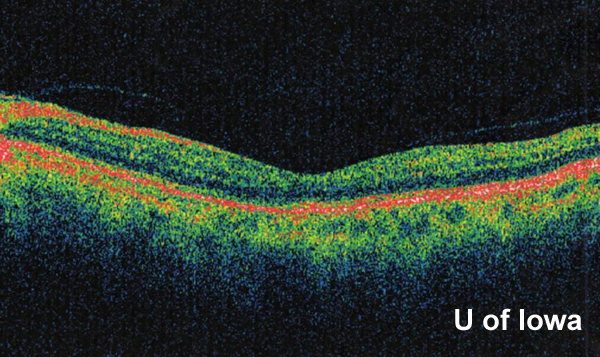

There was suspicion for subretinal fluid tracking into the macula, but this was not clearly evident on fundus exam alone. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) was performed and did confirm subretinal fluid extending throughout the macula (see Figure 3).

|

Clinical Course: At this point, several possible diagnoses were considered. The patient had no pain, the optic disc edema was sectoral, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was negative making demyelinating disease less likely. Ischemic optic neuropathy was a consideration, but the patient is of the wrong age, in overall good health, and without any symptoms of giant cell arteritis. Neuroretinitis was also considered as a possible diagnosis.

The patient was asked about pets, and she volunteered that she has cats at home. When asked about scratches from the cats, she rolls up her sleeves and shows multiple examples of scratches from 3-4 weeks old.

Laboratory work-up was initiated and results included:

The infectious disease team was consulted for what appeared to be cat-scratch disease (ocular bartonellosis). They agreed with that assesment and recommended treatment based on reasonable indicators of poor vision, high titer, elevated white blood cell count, and known scratch from a cat. A review of the literature suggested that a one month course of doxycycline or erythromycin (with or without rifampin) is adequate to treat the organism and hasten recovery. Consistent with their recommendation, we treated the patient with a one month course of doxycycline 100 mg PO twice daily.

The patient returned for follow-up appointments one and two months after this initial diagnosis. At these follow-up appointments, the patient was found to have vision improving to 20/60 in the affected eye, improving visual fields (Figure 4), decreased optic disc edema (Figure 5), and resolving sub-retinal fluid (Figure 6).

|

|

| 4A: Repeat GVF, OS at 1 month follow-up demonstrates significant improvement with a much reduced cecocentral scotoma. | 4B: GVF, OS at 2 month follow-up confirms stabilization of the visual field. |

|

|

|

Cat-scratch disease is caused by the organism Bartonella Henselae. There are approximately 22,000 cases of in the United States every year. Diagnosis of the disease officially requires 3 out of 4 criteria:

As a matter of fact, we only have 2 of the 4 criteria in this case since the patient was not found to have identifiable lymph nodes at the time of examination.

Bartonella is transmitted from the flea, to the cat, to (potentially) the human host. Ophthalmic manifestations of Bartonellosis may occur in up to 13% of patients with systemic cat-scratch disease and includes:

Treatment is controversial. In fact, it has been well documented that patients will almost always get better on their own. However, literally hundreds of reports exist suggesting different regimens used to treat the condition and shorten recovery times. Treatments include doxycycline, erythromycin, rifampin, azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, later addition of steroid drop, and many others. A review article published in the American Journal of Ophthalmology (Cunningham & Koehler 2000) suggests a one-month course of doxycycline or erythromycin, with or without rifampin.

After resolution of the disease, final outcome can include residual visual field defect, decreased contrast sensitivity and visual acuity, and sectoral disc pallor on exam. Classically, a macular star of lipid exudates is seen as subretinal fluid is resorbed (see Figure 7 for a classic macular star). Indeed, most cases of unilateral macular star with optic disc swelling is related to ocular bartonellosis, as is the case with this patient's (however, a differential diagnosis is offered below). Eventually, the macular exudates also resolve.

|

EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

OCULAR SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

| TREATMENT

|

Longmuir RA, Lee A. Cat-Scratch neuroretinitis (Ocular bartonellosis): 44-year-old female with non-specific "blurriness" of vision, left eye (OS). EyeRounds.org. March 31, 2005; Available from: http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/36-CatScratchBartonella.htm.

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.