History of Present Illness: 36-year-old East Indian male with progressive decrease in vision the right eye (OD) for 6 months. The vision is generally depressed, with no discrete scotomas.

Past Ocular History: None known to the patient.

Medical History: Patient has Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) with Humun Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) transmitted through intercourse with a prostitute. The last known CD4 count was 9 cells/mm3. Patient also has a history of Tuberculosis.

Medications: The patient was very recently placed on Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) and anti-tuberculosis therapy.

Family History: The patient’s wife is also HIV+ due to transmission from the patient.

Social History: The patient denies any other sexual contacts since his diagnosis of HIV+.

|

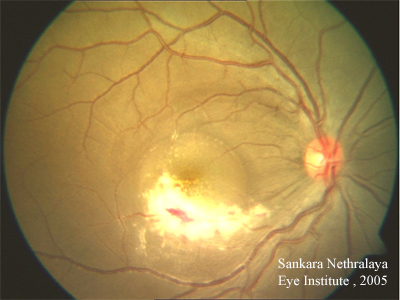

Course: In summary, this is a 36-year-old patient with AIDS, low CD4 count of 9 cells/mm3, recently placed on HAART therapy with progressive decrease in visual acuity in the right eye for the past 6 months. Associated ocular findings include vitritis and patchy area(s) of retinal necrosis with irregular borders and overlying retinal hemorrhages. The patient’s history, symptoms, and signs are consistent with CMV retinitis OD. With the very recent initiation of HAART, the patient has not had much time to build up an immune response. In addition to the role that appropriate HAART therapy will play in fighting CMV, the patient also underwent induction therapy with intravenous ganciclovir therapy. It is thought that an intravitreal ganciclovir injection may also be helpful in this patient given the location of the lesion.

Discussion: CMV retinitis (CMVR) remains one of the most common opportunistic ocular infections of patients with AIDS. It is a disease of profound immunosuppression that occurs primarily in patients with CD4 T-lymphocyte counts of 50 cells/mm3 or less. Although advances in antiretroviral therapy, such as highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART), have significantly reduced the incidence of this disease, active CMVR in patients with higher T-cell counts can occur through the deletion of CMV-specific CD4 memory cells or blunted T-cell response.

HAART is a combination of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and at least one protease inhibitor or nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor. The combination has proven to significantly reduce the number of plasma HIV messenger RNA copies and to increase the number of CD4+ T lymphocytes. Since the use of HAART, the incidence of CMVR has declined by 50% to 80%. The strongest predictor for CMVR in the pre-HAART era was the absolute CD4 count, and the risk was directly correlated with lower CD4 counts.

Symptoms of blurred vision, floaters, and flashes of light are highly variable and depend on the location and size of the lesion and on the immune status of the host.

The retinitis begins as small, white perivascular retinal infiltrates or dot-blot hemorrhages. The classic lesion is a hemorrhagic necrotizing retinitis that follows the retinal vasculature. When fluffy retinal infiltrates and necrosis are associated with scattered hemorrhages, this creates what has been called the "scrambled eggs and ketchup" appearance of severe CMVR. Clusters of small white dots representing retinal infiltration may precede the leading edge of the lesion as it advances. Large areas of necrosis can lead to retinal tears and detachment, ending in blindness within 4 to 6 months. Another form of CMVR is a white granular geographic lesion that clears centrally as it enlarges, leaving a quiet central area of retinal atrophy and mottled retinal pigment epithelium—this has also been described as a "brush-fire" pattern. Because the retinitis advances at a relatively slow rate, it is important to observe these patients carefully, ideally with serial photography, to detect progression. CMVR is categorized as a standard measure by the most posterior extent of the lesions into Zone 1, Zone 2, and Zone 3. The risk of retinal detachments may be up to 50% at 1 year after onset of active CMV retinitis.

Other uncommon forms of ocular CMV disease include isolated iritis and frosted branch angitis. Systemically, CMV can also cause esophagitis, colitis, pneumonitis, and sinusitis in immunocompromised patients.

Before the advent of HAART, patients with CMVR could expect induction anti-CMV drug therapy followed by lifelong maintenance therapy to suppress retinitis and to prevent or postpone the otherwise inevitable loss of vision.

HAART has been shown to prolong the disease-free interval as much as threefold for patients with existing CMVR. Additionally, anti-CMV maintenance therapy has been safely withdrawn from patients with prolonged immune recovery resulting from HAART. Treatment regimen should be based on degree of ocular involvement, location of retinitis, current and expected immune status, underlying medical conditions, access to medical care, and lifestyle preferences. For antiretroviral-naïve patients about to begin HAART, the goal should be to stabilize the retinitis while awaiting recovery of the immune system.

In the United States, four medications are currently approved for treatment of CMV retinitis: ganciclovir, foscarnet, cidofovir, and valganciclovir. Treatment of CMV retinitis may prolong the survival of patients with AIDS.

Ganciclovir is a useful first-line therapy intravenously (IV). Oral ganciclovir has poor absorption and is used for maintenance or in conjunction other therapy. In 80-90% of patients, IV administration of ganciclovir or foscarnet twice daily (induction therapy) (5mg/kg) for 21 days initially halts retinal-cell necrosis and reduces viral recovery from urine and blood. After 2-3 weeks of induction therapy, patients are usually switched to maintenance therapy with daily intravenous infusions. Intravitreal ganciclovir allows high doses in the eye and decreases systemic complications by allowing lower systemic concentrations administered with intravitreal injections. Intraocular ganciclovir also helps to prevent progression when the macula or optic nerve is threatened. Intravitreal ganciclovir is given as 1mg in 0.1mL twice weekly in active CMV retinitis and once weekly for maintenance. Commercially available intraocular ganciclovir implants do seem to be useful for prolonged medication delivery to the intravitreal space, but these need replacing regularly. Foscarnet is useful in patients with either resistance to ganciclovir or systemic toxicity (see chart below for systemic toxicities of these antiviral drugs).

Once patients are on HAART, caution must be taken within the first 6 months of HAART initiation because of susceptibility to recurrent retinitis. After reconstitution of the immune system and a CD4 count greater than 100 cells/mm 3 for 6 consecutive months, anti CMV maintenance therapy can be withdrawn.

Relapse of retinitis is a sign of worsening function of the immune system, inadequate intraocular drug levels, or development of resistance to the agent used. Reinduction with the same or a different anti-CMV agent can reestablish control, however the interval between relapses progressively shortens.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT

|

Muthialu A, Folk JC. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Retinitis: 36-year-old Indian male with HIV and decreasing visual acuity. EyeRounds.org. December 18, 2006 ; Available from: http://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/cases/61-CMV-Cytomegalovirus-Retinitis-HIV.htm, 2006

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.