Chief Complaint: 1-week-old male infant in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit referred for eye examination for possible TORCH infection.

History of Present Illness: The patient was born at 39 4/7 weeks gestation with a birth weight of 3498 gm to a 24-year-old G2P0 (now P1) mother. A pre-natal ultrasound revealed large lateral ventricles and a prominent third ventricle; there were no other abnormalities seen at that time. The pregnancy was also complicated by gestational diabetes and maternal cigarette smoking. The delivery was complicated by maternal fever, fetal tachycardia, and respiratory distress secondary to meconium aspiration. The patient was initially intubated but was weaned to room air after stabilization in the NICU.

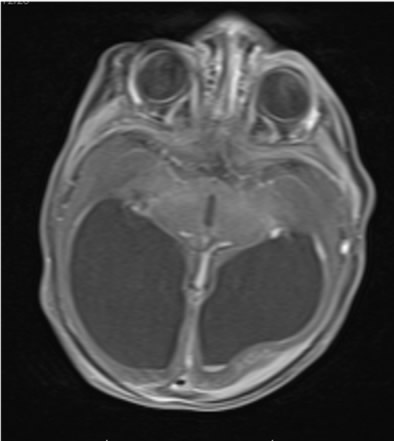

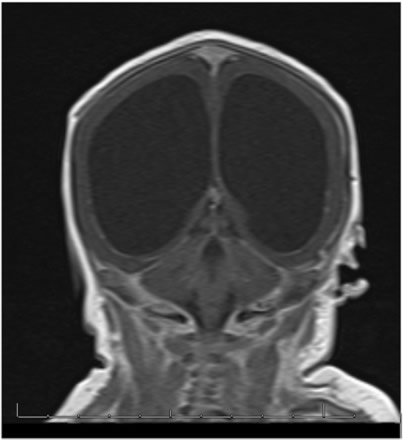

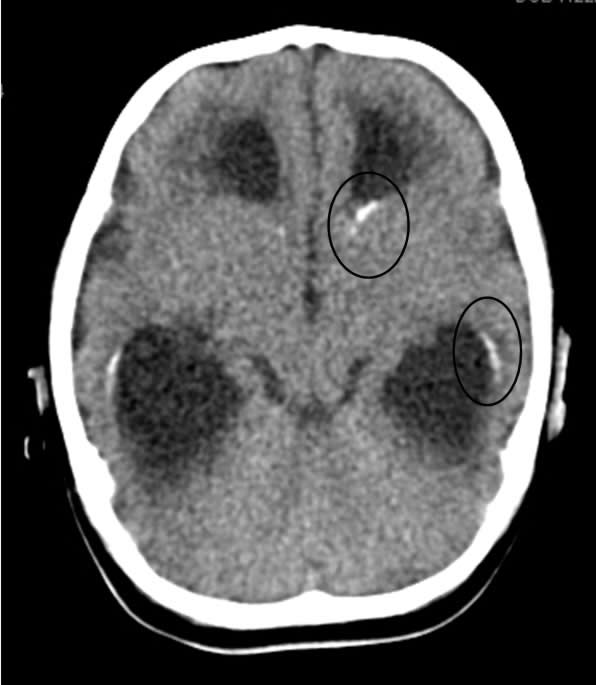

Because of the abnormal findings on the pre-natal ultrasound, an MRI of the head was performed on the first day of life (Figure 1). This revealed marked hydrocephalus and bilateral intraventricular hemorrhage. Due to concern for intracerebral calcification, a CT scan was later performed which demonstrated periventricular calcification suggestive of an intrauterine "TORCH" infection (Toxoplasmosis, Other, Rubella, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) (Figure 2). An ophthalmology consult was requested to evaluate for ocular findings consistent with a TORCH infection.

|

|

|

Past Ocular History: This was the patient's first eye exam.

Medical History: In addition to the history above, the patient had failed a hearing screening in his left ear the day before ophthalmologic evaluation.

Family History: No family history of neurologic or ocular disorders. The mother denied a history of sexually transmitted disease or any illness during pregnancy. She reported some close contact with cats but denied handling litter boxes or being exposed to their excrement.

Social History: Noncontributory.

Newborn Ocular Exam:

|

|

Neurosurgery was consulted for evaluation of the child's hydrocephalus and found no indication for emergent shunting.

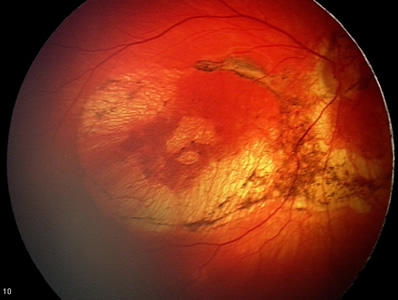

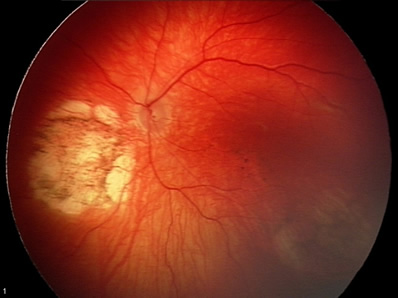

With regards to the ophthalmologic findings, it was felt that the lesions most likely represented chorioretinal scarring from inflammation or infection. Due to the fact that the abnormalities were bilateral, an inherited etiology was considered but felt to be unlikely.

The Infectious Disease service was consulted. Due to the constellation of findings that included chorioretinitis, hydrocephalus, intracerebral calcification, and hearing loss, intrauterine TORCH infection was felt to be the best unifying diagnosis. The classic TORCH infections, namely Toxoplasmosis, Rubella, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV), were initially considered. However, workup including urine culture for CMV and serum Toxoplasma IgM and IgG titers were negative. Also, the mother was Rubella immune, had a negative VDRL, and had no history or signs of HSV.

Subsequently, attention was turned towards testing for lesser known, but increasingly recognized infectious agents. The patient's serum was drawn for antibody titers to Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus (LCMV). Serum IgG was significantly elevated (>1:256) and IgM was within normal limits, which was felt to be consistent with prior infection.

The patient did eventually undergo a shunting procedure for his hydrocephalus. He has been discharged home. His retinal findings have been stable on serial exam.

Based on the appearance of the retinal findings, inflammatory or infectious causes were at the top of our differential diagnosis. However, inherited disorders were also considered. Aicardi syndrome, and X-linked disorder associated with peripapillary retinal "lacunae" and brain malformations seemed to be a potential fit, however, this syndrome is fatal in males. Other genetic diseases such as choroideremia and gyrate atrophy would be unlikely to present so early in life and with coincident central nervous system pathology. Finally, the lack of neurologic and ocular disorders in the patient's family history, along with the hydrocephalus, intracerebral calcifications, and hearing loss pointed to intrauterine infection as the most likely cause of the findings.

"TORCH"pathogens, a group of pathogens capable of crossing the placenta during maternal infection, have been identified worldwide as causes of significant perinatal morbidity and mortality. TORCH infections include Toxoplasmosis, Rubella, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV), and other infections such as Syphilis, VZV, EBV, HIV, West Nile Virus, parvovirus, and LCMV. When these cross the placenta from infected mother to fetus, the result may range from minor rash to spontaneous abortion. A brief explanation of each of the TORCH infections follows.

Toxoplasmosis is an infection from the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii, whose only definitive host is the domestic cat. It is for this reason that pregnant women are routinely advised against handling litter boxes that harbor cat waste during pregnancy. The majority of infants infected with Toxoplasmosis are asymptomatic at birth, but the classic triad of symptoms includes chorioretinitis, hydrocephalus, and intracranial calcifications. Serum testing for anti-Toxoplasma gondii IgM and IgG antibodies usually facilitates a diagnosis. Pyrimethamine plus sulfadiazine can be effective as drug treatment for acute infection or for recurrences. Unfortunately, the damage to the fetus that may have already occurred is irreversible.

Rubella is a viral disease also known as "German Measles," which has been virtually eliminated in the United States due to contemporary vaccination practices. While the disease may be mild in children, it can cause serious fetal abnormalities if contracted during the first trimester of pregnancy. Fetal abnormalities may include mental retardation, heart disease, deafness, and eye defects such as cataracts, glaucoma, and retinal damage. Another classic sign of Rubella is the "blueberry muffin" rash. Treatment for congenital infection is primarily supportive. A mother's immunity against Rubella is routinely tested for in the United States.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a common and widespread infectious agent, which affects approximately 40,000 infants born in the United States each year. CMV has a mortality rate of 20%, but survivors usually suffer from significant neurologic morbidities. Chorioretinitis occurs in 15-20% of cases. Diagnosis of CMV infection in the newborn is usually made via urine culture. Even though CMV is the most common viral infection in infants, there is no cure. Treatment is primarily supportive. Ganciclovir and foscarnet may have some utility in selected cases.

Congenital Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) is often contracted from the infected mother's genital tract during delivery. As such, signs and symptoms are usually not evident in the newborn until 5-15 days post-birth. Common findings include intracranial calcifications, respiratory distress, conjunctivitis, keratitis, chorioretinitis, and microphthalmia. Diagnosis can be made via viral culture or PCR.

Other. As our diagnostic abilities improve, the list of pathogens that are known to cause intrauterine infection grows longer. Syphilis, VZV, EBV, HIV, West Nile Virus, parvovirus, and Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus (LCMV) have all been identified as pathogens that can cause intrauterine infections.

LCMV is a virus that is becoming increasingly recognized as a dangerous pathogen. LCMV has been isolated from several clusters of patients that died suddenly after solid organ transplant, and reports of its ability to cross the placenta and cause serious intrauterine infection are abundant. This has led to increased awareness of LCMV among physicians specializing in transplant medicine, obstetrics, and infectious disease.

LCMV was first reported to cause congenital infection in 1955. Its natural hosts are rodents, primarily mice and hamsters. Humans can be infected when they come into contact with the droppings or saliva of infected animals. In congenital infection it is thought that the virus accesses the CNS through the choroid plexus and replicates in ependymal cells and meninges. Necrotizing ependymitis causes aqueductal obstruction and hydrocephalus, and the immunologic response causes chorioretinitis. In a review of congenital LCMV infections, conducted at the University of Iowa (3), there was a 35% infant mortality associated with congenital infection. 88% of the children had chorioretinitis; 76% of these cases were bilateral. A majority of the survivors had severe neurologic sequelae. It is very likely that our patient may have permanent visual and neurologic deficits.

Serologic testing for anti-LCMV IgM and IgG antibodies is available for diagnosis. In our case, it was felt that the clinical findings along with the elevated IgG antibodies were indicative of intrauterine LCMV infection. There is no proven treatment for LCMV and treatment is primarily supportive. Antivirals such as ribavirin and acyclovir have been used in transplant patients without demonstrable effectiveness.

Diagnosis: Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus (LCMV, categorized as "Other" in TORCH infections)

EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT

|

Wendel LJA, Jensen L, Longmuir SQ. Congenital Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus (LCMV) infection: 1-week-old male with hydrocephalus and bilateral chorioretinitis. EyeRounds.org. February 2, 2009; Available from: http://www.eyerounds.org/cases/91-LCMV.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.