Chief Complaint: The patient was a 51-year-old male seen in consultation from the internal medicine service for evaluation and management of "dry and red eyes."

History of Present Illness: The patient has a history of hyperthyroidism which was diagnosed 2 years ago and had been managed medically until he developed agranulocytosis on tapazole and had other complications while on methimazole and propylthyiouracil. On presentation to the eye clinic, he was complaining of horizontal binocular diplopia on extreme up-gaze. He was not bothered by the diplopia. He had some complaints of blurry vision in the morning.

PMH/FH/POH: His ocular history was not significant as he had no prior history of ocular surgery, trauma, or ambylopia.

|

|

|

| Full HVF OS. | Depressed HVF OD. |

|

|

A diagnosis of compressive Graves' ophthalmopathy was made. The patient had a Free T4 of 4.7 nanograms/dL and TSH of 0.2 micro IU/mL. The patient underwent a thyroidectomy for treatment of his hyperthyroidism because he failed medical management. Due to his RAPD, decreased flicker fusion, and visual field defect OD, oral prednsione 100 mg PO once daily was started. After one week, the prednisone was tapered to 80 mg PO once daily. The prednisone was slowly tapered thereafter based on his examination.

Radiation oncology consultation was obtained for radiation therapy (RT). He received a total of 2000 cGy delivered in 10 fractions utilizing right and left lateral fields composed of 4 MV photons prescribed to the 98 percent isodose line. The patient tolerated the RT without any complications.

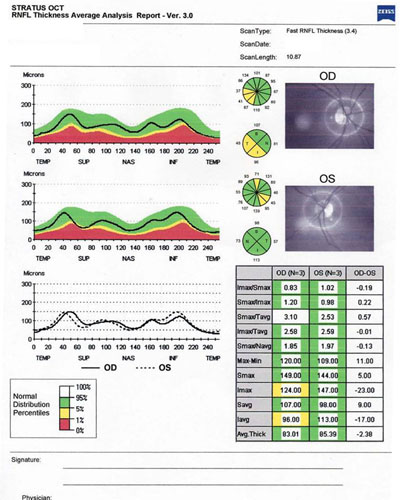

He returned to the clinic two weeks after treatment was begun. His visual acuity improved to 20/25 OD and 20/20 OS. His PEE decreased with frequent use of artificial tears and lubrication at night. His RAPD decreased to 0.6 OD, and the flicker fusion was improved with 29.0 ms OD and 31.0 ms OS. His ocular motility also improved with less restriction in up gaze. Humphrey visual fields (Figure 5) were obtained which demonstrated improvement in the field deficit OD.

|

|

| Before treatment. | After treatment. |

At this point the patient was slowly tapered off his steroids and monitored for optic nerve compression by frequent monitoring of visual fields and RAPD.

Characteristic signs of Graves’ ophthalmopathy include proptosis, periorbital edema, ocular irritation, ocular redness, and injection of the rectus muscle insertions. Blurring of vision and diplopia are other symptoms. Loss of vision may be due to compressive optic neuropathy (CON). Approximately 90% of patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy present with eyelid retraction. The classic constellations of Graves' ophthalmopathy are: eyelid retraction, exophthalmos, optic nerve dysfunction, extraocular muscle thickening, and hyperthyroidism (found in 5% of patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy). It is also possible to have Graves’ ophthalmopathy without thyroid dysfunction which is called euthyroid Graves’ disease.

It has long been felt that the pathogenesis of the extraocular muscle thickening in Graves’ disease was due to the accumulation of hydrophilic glycosaminoglycans within the muscle, such as hyaluronic acid. The accumulation of glycosaminoglycans causes the change in osmotic pressure and leads to an increase of fluids, which interferes with muscle function and increases orbital pressure. In addition, it is now felt that adipogenesis is thought to play a major role in the pathogenesis of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Most of the evidence points to the TSH receptor as the antigen that initiates the immune response triggering the activation of T-cell activity. The sequence of pathogenesis includes: T-cell activation, antigen recognition, cytokine/chemokine release, and manifestation of disease due to pathogenesis of the target cell and tissue remodeling. Fibroblasts are believed to be the primary target cell mediating perpetuation of disease.

Risks factors for worsening of Graves’ ophthalmopathy include smoking (Prummel, 1993) and diabetes. Smokers with elevated T3 levels appear to be at greatest risk for exacerbation of ophthalmopathy when I-131 is used. All patients should be counseled to stop smoking because smoking cessation can limit the severity and progression of Graves’ ophthalmopathy.

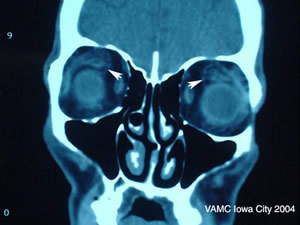

Evaluation for compressive optic neuropathy (CON), a vision-threatening complication of Graves’ ophthalmopathy, should include the following tests: visual acuity, RAPD, Hertel ophthalmometry, automated or Goldmann visual fields, and MRI or CT scans of the orbits. Because our patient exhibited numerous clinical findings consistent with CON but did not present with marked proptosis, CON can be devastating in this setting due to the tightness and small volume of the orbits.

Treatment of Graves’ ophthalmopathy begins with treatment of the underlying thyroid disease. It has been noted that some patients tend to have worsening of their ophthalmopathy when the hyperthyroidism is treated; therefore, it has been recommended that patients be started on steroids during the treatment of the hyperthyroidism to prevent this complication. The physician should determine whether or not steroids are indicated based on the clinical presentation.

Treatments for dry eyes associated with Graves’ disease include artificial tears, lubricants at night, and punctal plugs to prevent drying of the cornea and exposure keratopathy. In patients with severe proptosis, bilateral lateral tarsorrhaphy may be necessary to prevent corneal damage.

Corticosteroids have been demonstrated to decrease extraocular muscle enlargement and proptosis and improve vision in Graves’ ophthalmopathy (Prummel, 1989). In the event of CON, it is advised that corticosteroids be given (Hatton, 1992). The treatment of CON may also incude orbital RT and surgical orbital decompression.

Low dose radiotherapy (RT) has been reported with good results for the treatment of acute inflammation and CON in Graves’ ophthalmopathy. RT is believed to work by lympholysis or killing of retro-orbital T-cells which are responsible for activating the immune response involved in the muscle inflammation and enlargement. Treatment with RT is generally 2000 cGy. Previous head or orbit radiation is a contraindication. Risks associated with RT include: cataract, neoplasm, radiation optic neuropathy, and radiation retinopathy. Patients with diabetes who are at increased risk for CON are also at risk for retinopathy from RT and this should be considered in treatment strategy. RT and steroids have been found to significantly reduce the proptosis, diplopia, and CON. Oral and IV steroids are both effective, but IV steroids may be better tolerated and more effective (Marcocci, 2001).

Indications for orbital decompression surgery include the failure of steroids or RT to stop progression of ophthalmopathy, loss of vision due to CON, or cosmetic correction of severe proptosis. Approximately 20% of patients undergo surgery for Graves ’ ophthalmopathy.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT

|

Quisling S, Lee AG: Thyroid Eye Disease (Graves' ophthalmopathy): 51-year-old male seen in consultation from the internal medicine service for evaluation and management of "dry and red eyes." February 21, 2005; Available from: http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/case19.htm.

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.