Chief Complaint: Watery, irritated eyes

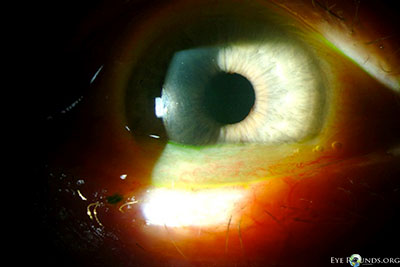

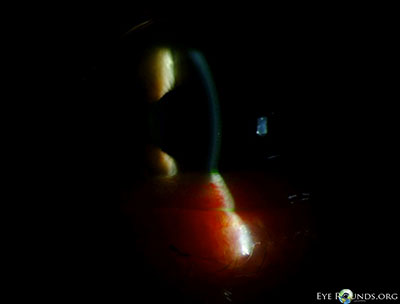

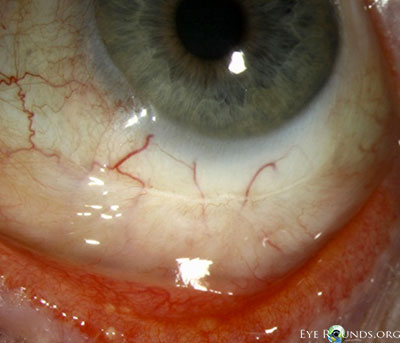

History of Present Illness: This patient was a healthy 76-year-old woman with complaints of irritated, red, and watery eyes. She had been followed in our clinic for these concerns and was being managed with doxycycline 100 mg daily, Lotemax® (loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension) daily to both eyes, artificial tears, and artificial tear ointment to both eyes. She felt this regimen had helped relieve some of her symptoms, but was still bothered by ocular irritation, intermittent epiphora, and blurriness of her vision while reading.

|

|

|

|

|

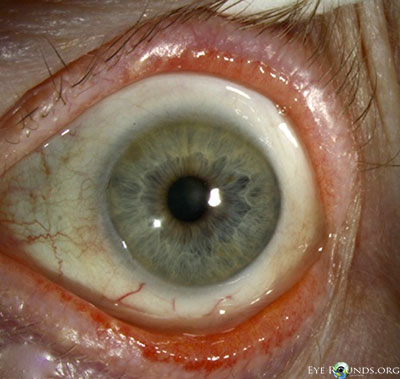

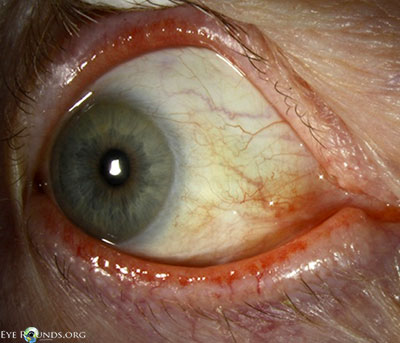

Given her symptoms and failure to respond to medical management as well as the marked conjunctivochalasis, the patient elected to proceed with surgery. The operative plan included resection of the excessive inferior and nasal bulbar conjunctiva with placement of an amniotic membrane graft. She underwent the procedure first on her right eye and noted a great amount of improvement in her symptoms, especially the blurriness while reading. The same operative procedure was performed four months later in her left eye. She was followed for over one year after surgery on her right eye (and over six months postoperatively on her left eye) and continued to be symptomatically improved compared to preoperatively.

Conjunctival resection with amniotic membrane graft for conjunctivochalasis

If video fails to load, see https://vimeo.com/59018451

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conjunctivochalasis (CCh) is defined as redundant conjunctiva. Hughes first coined this entity in 1942; [1] however the description of loose, nonedematous conjunctiva had been first reported as early as 1908 by Elschnig.[2] It is most often evident between the globe and the lower eyelid, but in more advanced cases can be evident around the entire globe. The majority of cases are bilateral, and often conjunctivochalasis is overlooked as a normal variant associated with the aging process if the patient is asymptomatic. In cases where the patient is symptomatic, common symptoms include: tearing, foreign body sensation, ocular irritation, and blurriness, especially in down gaze. It is important to keep this condition in the differential of chronic ocular irritation and epiphora.

Conjunctivochalasis is a common finding among older adults. Studies suggest that conjunctivochalasis is more common in patients who have dry eye and meibomian gland disease/blepharitis and is associated with contact lens wear.[3] The etiology of conjunctivochalasis is not well understood. Theories include that it could be a natural aging process of the conjunctiva or that it could be due to lid position abnormalities, ocular movements, ocular irritation, and eye rubbing. Some histopathologic studies demonstrate elastosis, chronic, nongranulomatous inflammation, fragmentation of the elastic fibers, and loss of collagen. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are enzymes that modify or degrade the extracellular matrix. MMP-1 and MMP-3 enzymes have been noted to be overexpressed in conjunctivochalasis fibroblasts in tissue culture, while the enzyme levels of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) are unchanged. The change in the balance between these two groups of enzymes may facilitate the breakdown of the extracellular changes and lead to the clinically evident changes observed in conjunctivochalasis.[4] Another hypothesis is that pressure from the eyelids may lead to impaired lymphatic drainage of the conjunctiva, which is supported by findings of lymphangiectasia, fragmentation of the elastic fibers, and no signs of inflammation on histopathology.[5]

If the patient has conjunctivochalasis but is asymptomatic, no treatment is necessary. For symptomatic patients, medical treatment is recommended as the initial step. Medical management includes the use of ocular lubricants, antihistamines (if there is a component of allergic conjunctivitis), and topical steroids. In cases where medical management is insufficient in improving the patient's symptoms, surgical intervention may be necessary. Surgical management is directed at resecting the redundant conjunctival tissue. Several methods have been described in the literature. The most common methods of surgical intervention include a crescent-shaped conjunctival resection with or without sutures, resection with placement of an amniotic membrane graft (with either sutures or fibrin tissue glue or both), or suture fixation of the redundant conjunctiva to the globe (without resection). During procedures where the conjunctiva is resected, a crescent of tissue can be marked, excised, and left to heal or closed with absorbable suture. Another method of resection is to make a limbal peritomy, extend posteriorly with relaxing incisions, and then pull the conjunctiva anteriorly, resecting the excess tissue that extends past the limbus.[6] The conjunctiva is then re-approximated near the limbus. Lastly, amniotic membrane grafting is an option. Once the area of conjunctiva is excised, an amniotic membrane graft is secured to the globe corresponding to the excised conjunctival defect, secured with fibrin tissue glue or absorbable suture, or a combination of the two.[7,8]

Success rates of the various methods appear to be similar. Moderate to high rates of improvement in symptoms have been reported. In a study by Yokoi and colleagues, an improvement of symptoms was found in 88.2% of patients that underwent resection of symptomatic conjunctivochalasis.[6] Similar success rates were reported by Tseng and colleagues.[8]

| Grade | Number of folds and relationship to the tear meniscus height |

|---|---|

1 |

No persistent fold |

2 |

Single, small fold |

3 |

More than two folds and not higher than the tear meniscus |

4 |

Multiple folds and higher than the tear meniscus |

Epidemiology

|

Signs

|

Symptoms

|

Treatment

|

Graff JM, Oetting TA, Kwon YH. Intralenticular Foreign Body : 23-year-old male with staple in the eye. EyeRounds.org. January 31, 2007 ; Available from: http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/63-Intralenticular-Foreign-Body-Open-Globe.htm.

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.