Chief Complaint: Episodic haloes around lights and blurry vision

History of Present Illness: This 24-year-old Caucasian man presented with the complaint of transient blurry vision and rainbow-colored haloes around lights with pressure sensation in either eye for several months. He estimated that these episodes occurred once every few weeks and they were sometimes provoked by playing soccer. The episodes lasted approximately 30-60 minutes. He reported no visual symptoms between episodes. He denied nausea, vomiting, or photophobia.

Past Ocular History: Significant for metallic corneal foreign body to right eye (OD) at age 15 with a resulting scar. No history of injury to left eye (OS).

Past Medical History: Healthy, no medications

Family Ocular History: Maternal grandfather with glaucoma

Figure 1: Slit lamp photograph showing a Krukenberg spindle visible on the corneal endothelium

Figure 2: Slit lamp photograph showing marked midperipheral radial iris transillumination defects

|

|

Figure 4: Gonioscopic photograph showing marked iris backbowing, a very deep anterior chamber, and heavy pigmentation of the trabecular meshwork

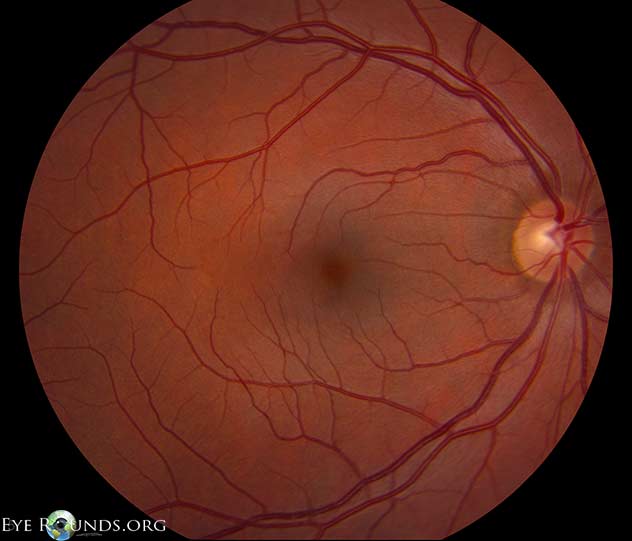

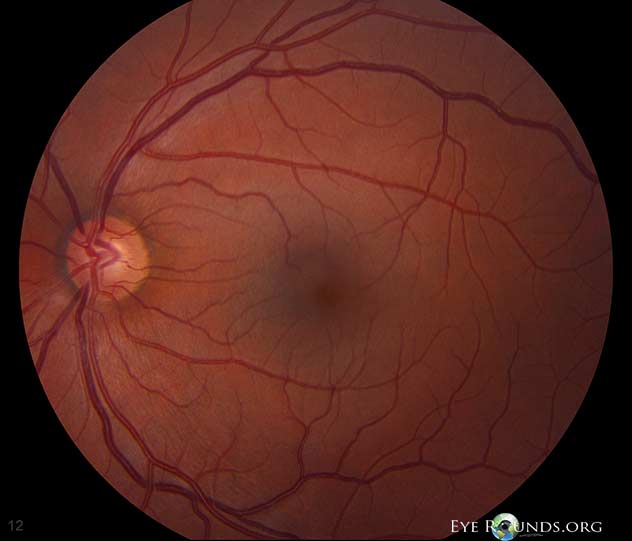

Clinical Course: The patient was diagnosed with pigmentary glaucoma involving the left eye more than the right eye. He had all the cardinal features of pigmentary glaucoma, including Krukenberg spindle, heavily-pigmented trabecular meshwork, iris backbowing with transillumination defects, Scheie stripe, elevated intraocular pressure, and changes of the optic nerve. He was started on latanoprost OU for elevated intraocular pressures. He underwent laser peripheral iridotomy OU, which changed his gonioscopic findings to E45f 4+ OU. He has remained stable for 2 years of follow up.

Discussion: Pigmentary glaucoma (PG) is glaucoma in the setting of pigmentary dispersion syndrome (PDS). The constellation of findings for PDS consists of corneal endothelial pigment (Krukenberg spindle), darkly-pigmented trabecular meshwork, prominent mid-peripheral iris transillumination defects, prominent back-bowing of the iris, and a Scheie stripe (pigment deposition on the junction of the posterior lens capsule and vitreous face, see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Gonioscopic photo demonstrating a Scheie stripe

Pigment dispersion occurs due to rubbing of the iris pigment epithelium against the lens zonules, typically because of a back-bowed iris. The loss of pigment results in mid-peripheral iris transillumination defects. Once liberated, the pigment is deposited in the posterior chamber as a Scheie stripe or travels to the anterior chamber, where it deposits on the corneal endothelium and in the trabecular meshwork. Studies of fluid dynamics show that there is a vertical circulation current of aqueous humor in the anterior chamber. This is hypothesized to result from a temperature gradient from the posterior portion of the anterior chamber (warmer, causing fluid to rise) to the anterior portion of the anterior chamber (cooler, causing fluid to fall). Deposition of circulating pigment onto the corneal epithelium gives rise to the vertical Krukenberg spindle. As lens thickness increases with age, “burnout" can occur, because the iris is displaced sufficiently to prevent further release of pigment from zonular abrasion.

PG is typically found in young, myopic individuals. Occasionally, these patients may report symptoms of high intraocular pressure, such as blurry vision, haloes around lights, headache, nausea, vomiting, or pressure sensation after jarring exercise such as basketball, tennis or soccer. It is hypothesized that jarring exercise exacerbates release of pigment, which transiently obstructs the trabecular meshwork, leading to increased intraocular pressure with its accompanying symptoms. Jogging, however, has been demonstrated to not produce elevated IOP.

If indicated, intraocular pressure can be lowered with topical anti-glaucoma drops. Pilocarpine is particularly effective in preventing pigment liberation by causing the iris to move forward, relieving the contact between the iris and zonules. However, because these patients are typically myopic and have higher risk of retinal detachment, cholinergic agonists must be used with extreme care. They are also poorly tolerated in young patients because of induced myopia.

Laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI) may be useful to relieve reverse pupillary block from the backbowing of the iris in selected cases. Of note, the rise in intraocular pressure after LPI in patients with PG is typically greater than in patients with narrow angles. The role of LPI in PDS and PG is controversial. Our patient had near-total loss of iris pigment epithelium in the left eye, which made LPI less desirable, because the pigment was almost all gone already. Laser trabeculoplasty is particularly effective in this condition as the laser is absorbed readily in the heavily-pigmented trabecular meshwork. Argon laser trabeculoplasty (ALT) is anecdotally preferred by some over selective trabeculoplasty (SLT) in patients with a heavily-pigmented trabecular meshwork due to the incidence of intraocular pressure spikes post-operatively in SLT, though a trial comparing the adverse events of both in pigmentary glaucoma has not been performed.

If eyedrops or laser treatments fail, trabeculectomy or seton placement can be used.

Diagnosis: Pigmentary dispersion syndrome/pigmentary glaucoma

EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT

|

Niyadurupola N, Broadway DC. Pigment dispersion syndrome and pigmentary glaucoma – a major review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2008; 36:868–882.

Alward WLM. Glaucoma: The Requisites in Ophthalmology. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Inc., 2000.

Haynes WL, Johnson AT, Alward WL. Inhibition of exercise-induced pigment dispersion in a patient with pigment dispersion syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1990;109:601–602.

Haynes WL, Johnson AT, Alward WL. Effects of jogging exercise on patients with pigmentary dispersion syndrome and pigmentary glaucoma. Ophthalmology 1992;99:1096–1103.

Harasymowycz PJ, Papamatheakis DG, Latina M, et al. Selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) complicated by intraocular pressure elevation in eyes with heavily pigmented trabecular meshworks. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;139:1110–1113.

Hager J, Alward WLM. Pigmentary Glaucoma: 24-year-old male with episodic haloes around lights and blurry vision. EyeRounds.org. February 17, 2014; available from https://eyerounds.org/cases/184-pigmentary-glaucoma.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.