INITIAL PRESENTATION

Chief Complaint: Black spot in the right eye

History of Present Illness:

The patient was a 17-year-old previously healthy female who presented with acute vision loss in the right eye after playing with a sibling at home. Her vision loss occurred suddenly following a handheld laser pointer being directed into both eyes. She presented to clinic one week after her initial injury as her vision loss had not resolved. On evaluation she noted a persistent "big black spot" in the center of her vision in the right eye, with an associated headache when focusing on fine detail. She denied photophobia, metamorphopsia, pain with eye movements, flashing lights,

Past Ocular History:

Medical History:

Medications:

Family History:

Social History:

Review of Systems:

OCULAR EXAMINATION

Differential Diagnosis:

CLINICAL COURSE

After being evaluated by an outside provider, the patient was referred to the vision rehabilitation service at the University of Iowa. Subjective history corroborated by the patient and family indicated that the patient was playing with a high-powered laser at the time the injury occurred. She was unsure of the power of the laser but acknowledged that her sibling pointed the laser directly into her eyes. Based on the clinical findings and additional testing, a diagnosis of laser pointer maculopathy was made. The patient was counseled extensively on the diagnosis and prognosis of this condition and was given return precautions should she develop progressive vision changes or metamorphopsia.

DIAGNOSIS: Laser pointer maculopathy

DISCUSSION

Etiology/Epidemiology

Laser pointer maculopathy is the result of laser injury to the retina. Though most frequently reported as a cause of unilateral vision loss, bilateral vision loss can occur with bilateral exposure [1-3]. Unfortunately, with the increasing availability of laser pointers, there has been a corresponding rise in reported ocular laser injury. Since 2014, worldwide cumulative reported laser injuries has more than doubled [3]. Though the recovery of laser pointer maculopathy is generally favorable, recovery to 20/20 vision has declined from 2010 to 2017. This may be due in part to the accessibility of higher laser powers to the general public [3]. Young men are most frequently affected by handheld laser pointer injuries [5], as well as those with learning or mental health issues [6].

In the United States, laser products are classified into six categories by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA): Class I, Class IA, Class II, Class IIIA, Class IIIB, and Class IV [7]. These categories as well as their power and ocular hazard risk are summarized in Table 1. Despite the growing public health risk [8], only twelve states currently have state-level laser regulations in addition to the federal provisions provided under the Radiation Control for Health and Safety Act of 1968 [7]. As a result, there are several reported cases of misclassified lasers sold with incorrect labeling that lead to inadvertent retinal damage [6].

|

Class |

Power |

Direct Ocular Hazard |

OSHA Labeled Hazard |

|

I |

0.4 μW |

None |

None |

|

IA |

40 μW |

After >1000 sec of exposure |

"Do not directly view with optical instruments" |

|

II |

<1 mW |

After >0.25 sec of exposure |

"Do not stare into beam" |

|

IIIA |

1-5 mW |

With any exposure |

CAUTION "Avoid direct eye exposure" |

|

IIIB |

5-500 mW |

With any exposure |

WARNING "Avoid exposure to beam" |

|

IV |

>500 mW |

With any exposure |

DANGER "Avoid eye or skin exposure to direct or scattered radiation" |

Signs/Symptoms

Patients may be asymptomatic initially but invariably present with blurry vision, central or paracentral scotomata, or metamorphopsias. The base eye exam should be conducted in a routine manner as anterior segment pathology, namely corneal punctate epitheliopathy, is also a well-known sequela of ocular laser injury [13]. In one case of repeated laser injury, superficial iris atrophy was also reported [14].

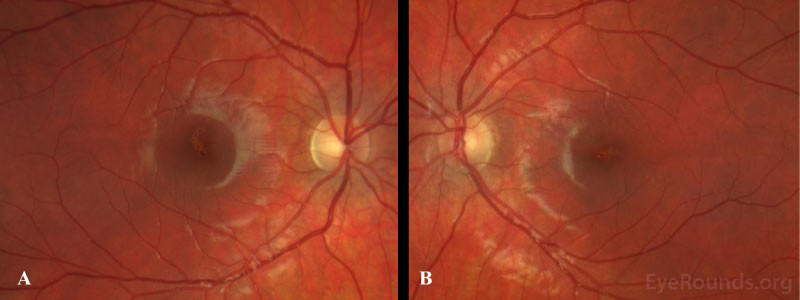

Fundoscopic examination shows yellow-white lesions or streaks, which may involve the foveal center. There may also be areas of hyper- or hypopigmentation, RPE mottling, and an attenuated foveal reflex. In some cases, patients with self-inflicted laser injuries seem to have scarring with a streak-like appearance, while injuries caused by others tend towards more focal scarring with closer proximity to the fovea [15]. Other posterior findings may include retinal hemorrhage, macular edema, choroidal neovascularization, epiretinal membrane (ERM), or a full-thickness macular hole [16-19]. Following resolution of the initial injury, the macula has a variable appearance ranging from normal to permanent scarring.

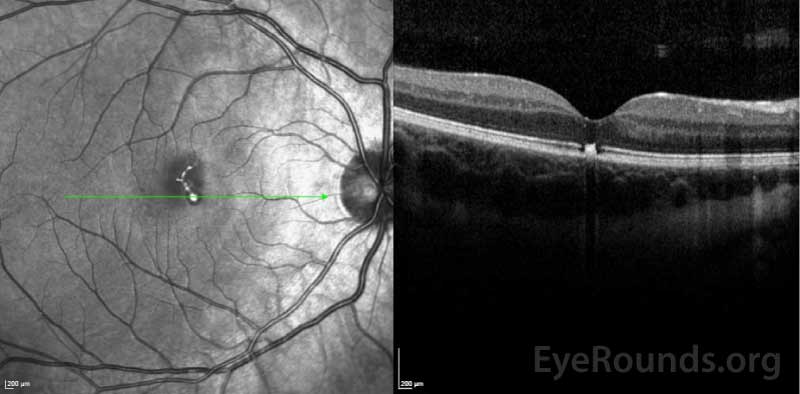

Testing/Imaging

Amsler grid testing during the initial encounter is a quick, non-invasive method of evaluating a central scotoma. In patients with suspected laser maculopathy, optical coherence tomography (OCT) should be performed. There is often profound focal disruption of the ellipsoid zone and RPE loss on OCT which, in conjunction with a classic history, are diagnostic of laser maculopathy [18, 20, 21]. Vertical hyperreflective bands involving the outer retinal layers may also occur [22-24]. Fluorescein angiography, if available, demonstrates delayed foveal hyperfluorescence and RPE window defects [25-27]. Fundus photography, while not necessary for diagnosis, demonstrates irregular pigmentary changes and RPE disruption as seen in our patient.

In the absence of a classic history, full-field and multifocal electroretinography (ERG) can objectively quantify retinal function. Preservation of retinal function beyond the focal injury is consistent with laser maculopathy [28]. There is also reported utility of adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (AOSLO) to further characterize photoreceptor damage, though this is seldom available in clinical practice [29].

Treatment/Management/Guidelines

Management of laser pointer maculopathy is expectant. Fortunately, the prognosis is favorable, and most patients recover over several months [2, 11, 30]. Those with significant injury, however, can have long-term visual deficits or scotoma. Lasers with a power >5 milliwatts carry a far worse long-term prognosis [3]. There are several studies that advocate oral corticosteroid use as this is thought to reduce the cellular inflammatory response induced by the laser [1 ,5 ,24 ,31 ,32]; however, larger prospective studies are required to demonstrate its clinical utility and effectiveness.

Patients who develop a macular hole or ERM should be managed according to the degree of visual impairment, with consideration given to the extent of injury and visual prognosis. Choroidal neovascular membranes (CNVM) may be managed with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents. If the extent of damage is visually debilitating, referral to a vision rehabilitation specialist may be considered. In all cases, preventative counseling should be undertaken to prevent repeated injury.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OR ETIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY |

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

|

References

Motlagh M, Wilkinson M. Laser Pointer Maculopathy. EyeRounds.org. March 18, 2021. Available from https://EyeRounds.org/cases/311-laser-pointer-maculopathy.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.