INITIAL PRESENTATION

Chief Complaint: Left eye pain

History of Present Illness:

A 24-year-old previously healthy female presented for acute onset left eye pain. She noticed gradual onset left superolateral orbital pain with accompanying edema and erythema of the left upper eyelid starting about 2 weeks prior to presentation. She could not recall any inciting or alleviating factors to her condition. Eyelid swelling improved after treatment with a course of amoxicillin-clavulanate. She denied changes in visual acuity, diplopia, history of sinus infection, trauma, and headache over this period of time.

Past Ocular History:

Medical History:

Medications:

Allergies:

Family History: :

Social History:

Review of Systems:

OCULAR EXAMINATION

Minimal tissue edema and erythema of the left upper eyelid with 0.5 mm of left ptosis (MRD1 of 3.5 mm OS and 4.0 mm OD; see Figure 1) and mild tenderness to palpation. There was 1.5 mm of proptosis by Hertel exophthalmometry on the left. 0mm of lagophthalmos OU. No hypoglobus noted.

Differential Diagnosis:

CLINICAL COURSE

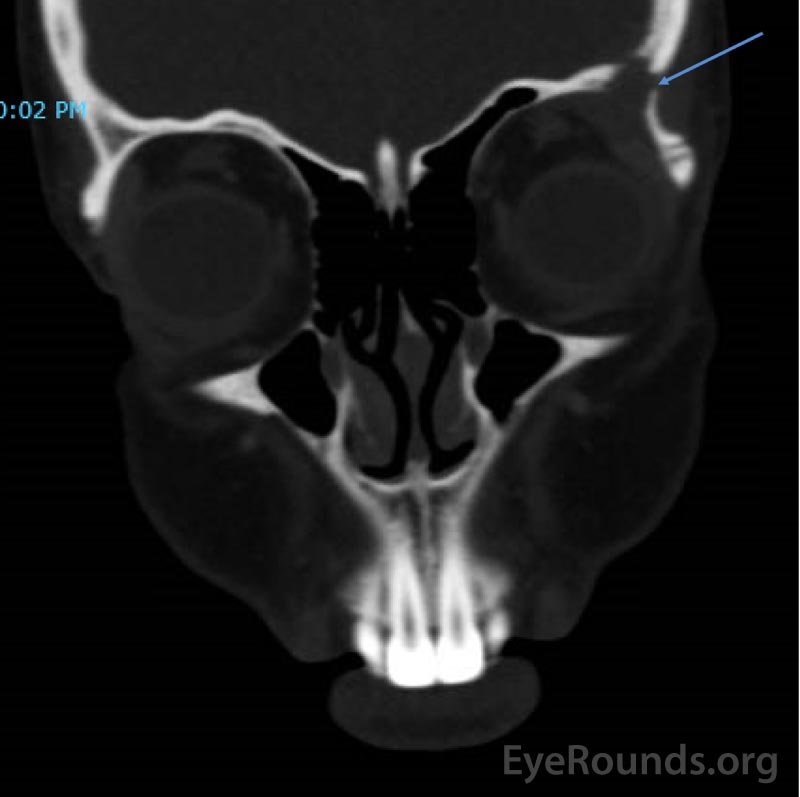

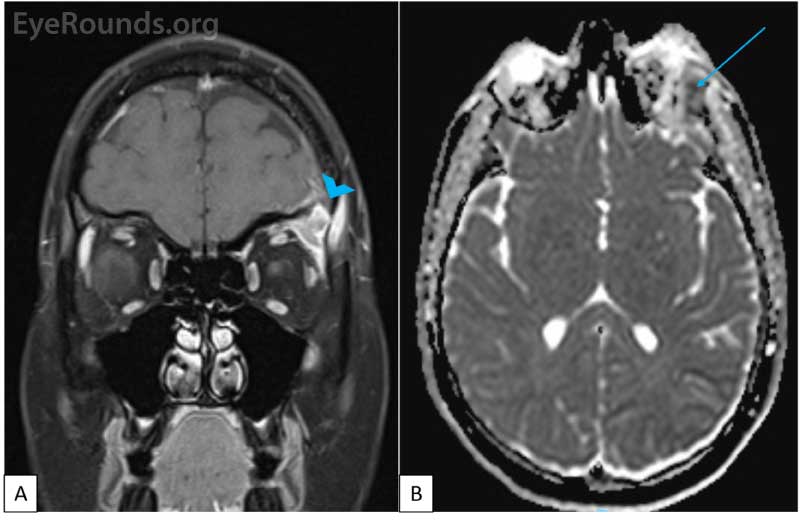

CT imaging obtained showed a dense osteolytic lesion in the left frontal bone in the region of the lacrimal gland fossa (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the orbit with contrast was obtained and revealed an enhancing lesion in the superolateral aspect of the left orbit which appeared to arise within the lacrimal fossa (Figure 3).

IMAGING

An anterior orbitotomy via an eyelid crease incision was performed and biopsy obtained. (Figure 4). Frozen section analysis revealed no carcinomatous cells and demonstrated infiltration of acute on chronic mixed inflammatory cells. Flow cytometry showed an atypical (53%) population of large histiocytic/monocytic cells which was confirmed on histopathologic evaluation with immunohistochemistry to be consistent with a Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis.

The patient was referred to an oncologist at UIHC before consulting with an additional local oncologist. Due to the location of the lesion with intracranial extension, this was considered a high-CNS risk lesion. A workup for central diabetes insipidus was undertaken (see Discussion) and was negative. Mutational analysis revealed a deletion in mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAP2K1; gene variant D43_F53delinsGAL; DNA change c.132_162delinsGGGGCGC). She was referred for treatment with cytarabine under the care of her local oncologist.

DIAGNOSIS

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

DISCUSSION

Overview

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is defined by proliferation of Langerhans cells. Formerly known by several names including "histiocytosis X", the term Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis was established in 1987 by the Histiocyte Society (1). LCH was initially thought to consist of three major subtypes: eosinophilic granuloma (solitary lytic bone lesions), Hand-Schuller-Christian disease (multifocal lytic bone lesions, proptosis, and diabetes insipidus), and Letterer-Siwe disease (disseminated, multisystem disease). However, LCH was subsequently recognized as a spectrum of disorders ranging from solitary, unisystem lesions to disseminated, multisystem disease (2). A variety of different classification systems based on the disease's biological origin and behavior have also been proposed, but are beyond the scope of this discussion.

Etiology/Epidemiology

LCH is considered a disease of childhood with a peak age of onset between 1 to 4 years (3). The incidence of LCH ranges from 2.6 to 8.9 per 100,000 children per year. In children younger than 1 year, the incidence ranges from 9 to 15.3 per 100,000, while the incidence in children older than 10 years ranges from 0.7 to 2.0 per 100,000 (2). However, LCH can occur at any age, with reports of cases in patients up to age 83 years (4). A review of 541 LCH cases by Islinger et al showed that 39% of patients were older than 21 years, with the mean age of disease onset in adult patients at age 32 years (5).

The sex distribution of LCH is debated. Islinger et al. reported both genders are impacted equally throughout childhood. They also noted a male predominance in adults (5) while others have reported male predominance at all age ranges (2 ,3). Differences in LCH incidence between race and ethnicity have also been observed. Hispanics have been shown to develop multisystem LCH at a higher rate when compared to white and black populations (6). SMAD6 has been shown to be a risk factor in genome wide association studies for developing LCH in Hispanic populations, which may explain the disparity between ethnicities (7). There does not appear to be any geographic association with developing LCH.

Pathophysiology

The underlying pathophysiology of these histiocytic disorders is not well understood. One theory regarding the pathophysiology of LCH implicates abnormal immune regulation (8). This hypothesis was prompted by the positive disease response to anti-inflammatory medications (i.e. corticosteroids) (8). Senechal et al. demonstrated a high number of T-regulatory cells in patients with LCH. Their group hypothesized the accumulation of Langerhans cells is likely due to abnormal survival instead of clonal proliferation secondary to T-regulatory cell signaling (9).

Recent work has focused on the involvement of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway. BRAF(V600E) oncogene is one of the genes within the MAPK pathway. Langerhans Cells with mutations of BRAF(V600E) have been reported in 55-63% of patients with LCH (10 ,11). Furthermore, Heritier et al showed LCH with the BRAF mutation were more likely to present as "high risk" disease. High risk LCH entails a higher chance of multiorgan involvement (liver, spleen, skin, bone marrow, lungs, etc.), increased resistance to therapies, and higher rates of reactivation (11). Our patient was found to have a deletion in the MAP2K1 gene, the clinical significance of which has not been fully elucidated (12). These mutated Langerhans cells secrete a variety of cytokines. Specifically, receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B (RANK), receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL), and osteoprotegrin have been shown to contribute to the osteolytic lesions, classically seen in LCH (13).p>

Signs/Symptoms

Ocular and Orbital Involvement

Typically, a patient may notice soft tissue fullness and erythema which is slowly progressive over weeks to months. Initially this may be misclassified as periorbital cellulitis (14). Pain over the lesion is frequently experienced (5). 11-24% of all LCH cases involve orbital structures, with the classic orbital presentation involving a lytic bone lesion in the superior or superolateral orbital region (15). It is unknown why LCH frequently involves orbital structures. Proptosis is seen in approximately half of LCH cases with posterior orbital involvement (14). Other reports have documented involvement of the eyelid, conjunctiva, caruncle, choroid, optic chiasm, orbital apex, and cavernous sinus, in addition to presentation with an epibulbar nodule (2). Depending on the location of the lesion, different cranial nerve palsies (CN VI and VII) have been reported. This can lead to ptosis, ocular abduction defects, hemifacial paresis, and lagophthalmos (15).p>

Systemic Involvement

A list of commonly involved extraocular sites are noted in Table 1. CNS-involving lesions commonly involve the hypothalamic-pituitary region, cerebellum, and brainstem (16). Central Diabetes insipidus (CDI) is a more common CNS manifestation of LCH. This association is hypothesized to be due to LCH infiltration of the pituitary gland or anti-vasopressin antibody production (17). 10-51% of CNS-involving LCH presenting with signs and symptoms of CDI. In many patients, CDI may develop after a diagnosis of LCH is established (18).

| Organ system involvements | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Lymph nodes (19%) | Liver (16%) |

| Spleen (16%) | Oral mucosa (13%)td> |

| Lung (10%) | Central nervous system (6%) |

Laboratory Work-up

Workup for these conditions is broad, and is necessary to rule out underlying systemic disease. A complete physical exam in addition to the below workup may help the clinician understand the breadth of disease.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

The diagnosis of LCH is established with examination of tissue samples. Fine needle aspiration is not recommended due to the possibility of inadequate tissue sample (2 ,14). The histiocytic infiltrate will predominantly consist of a clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells that appear more like macrophages than their usual dendritic shape. Immunopositivity for neuronal markers S100 and CD1a will confirm the presence of Langerhans cells and, thus, a diagnosis of LCH. Additionally, giant cells, eosinophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and macrophages are frequently observed in the field. On transmission electron microscopy, the presence of Birbeck granules (small rod- or tennis-shaped bodies) are considered pathognomonic for LCH. (2)

Laboratory studies

All patients should receive a CBC with differential, complete metabolic panel, coagulation profile, urine analysis urine osmolarity, and water deprivation test. Bone marrow biopsy and aspiration are also frequently recommended (2).

Imaging

Maxillofacial CT or MRI should be obtained evaluate involvement of the orbit, skull, remaining facial bones, and surrounding soft tissues. A skeletal survey, skull series, chest radiograph, and PET scan should be performed to evaluate for systemic disease and to serve as a baseline prior to treatment. Patients with suspected involvement of the liver or spleen should undergo dedicated abdominal CT, MRI, or ultrasound of these organs.

Treatment/Management/Guidelines

Management guidelines of LCH revolve around three categories of disease. These are unifocal, unisystem LCH (ex: isolated bone lesion), multifocal, unisystem LCH (ex: multiple bone lesions), and multisystem LCH (ex: bone and liver involvement). Management recommendations for each category is detailed in the paragraphs below.

Unifocal, Unisystem LCH

There are a variety of strategies for managing unisystem LCH. Treatment is chosen based on the perceived risk and location of the lesion. Typically, solitary osseous lesions are addressed if they involve areas with CNS risk (skull, spine), weight bearing areas, cause disfigurement, or develop in the pediatric population. If the lesion is small enough, it is recommended to curettage the lesion with intralesional injection of corticosteroid to aid with healing (16). Systemic therapy is discussed below in the multisystem LCH section.

Multifocal, Unisystem LCH and Multifocal, Multisystem LCH

These two classes of LCH disease are treated nearly identically. The age of the patient at disease presentation is commonly used to choose treatment regimens. The most common induction regimen for children (age <20 years old) with multisystem LCH is Vinblastine (6mg/m2 weekly intravenous bolus for six weeks) and Prednisolone (40 mg/m2/day orally for four weeks, and then tapered over two weeks) (16). If the patient is over the age of 20 then it is recommended to use either Cytarabine or Cladribine. Cytarabine is given at a dose of 100 mg/m2 for 5 days every 28 days (16). This regimen is preferred for adult patients with multisystem LCH and who may have CNS involvement, but no risk organ (bone marrow, liver, spleen) involvement. Cladribine is the preferred medication for patients with multisystem LCH who do exhibit risk organ involvement. Cladribine is typically given at a dose of 6 mg/m2 for 5 days every 28 days (16). More recently, Cytarabine has been used to treat the pediatric population. Despite improved therapies, disease recurrence occurs in approximately 1/3rd of patients (6). Guidelines for recurrence screening are not formally established and commonly left to the discretion of the treating oncologist. Primary care providers should assist with observing for signs of recurrence such as the development of diabetes insipidus.

ETIOLOGY/EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT

|

Bates B, Dickens D, Pham C. Langerhans cell Histiocytosis of the Orbit. EyeRounds.org. January 20, 2022. Available from https://EyeRounds.org/cases/318-Langerhans-Cell-Histiocytosis-of-Orbit.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.