INITIAL PRESENTATION

Chief Complaint: Decreased vision in the left eye

History of Present Illness: A 37-year-old woman presented urgently for evaluation of acute painless vision loss in her left eye. She noticed changes in her vision about one week prior to presentation, describing it as central blurring and distortion when trying to read small print. She denied any similar symptoms previously. She also denied any similar symptoms in her fellow (right) eye.

Past Ocular History: High myopia, both eyes

Medical History: Asthma

Medications: Daily multivitamin

Family History: Non-contributory

Social History: No history of tobacco or illicit drug use

Review of Systems: Negative except for what is detailed in the history of present illness

OCULAR EXAMINATION

Both eyes (OU): Normal

|

OD |

OS |

|

|

Vitreous |

Vitreous syneresis, no cell |

Vitreous syneresis, no cell |

|

Disc |

Peripapillary pigmentation |

Peripapillary pigmentation |

|

Cup-to-disc (C/D) ratio: |

0.2 |

0.2 |

|

Macula |

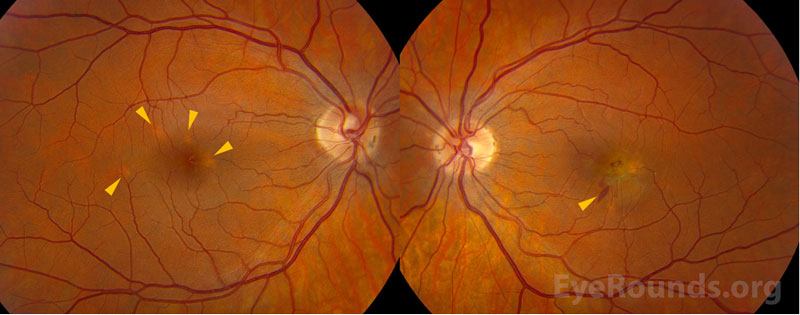

Few juxtafoveal hypopigmented spots |

Fovea-involving fibrovascular retinal pigment epithelial detachment with associated subretinal hemorrhage |

|

Vessels |

Normal |

Normal |

|

Periphery |

Few punched out chorioretinal spots with pigmentary change |

Few punched out chorioretinal spots with pigmentary change |

Differential diagnosis:

DIAGNOSIS: Punctate inner choroidopathy with choroidal neovascular membrane

CLINICAL COURSE

A diagnosis of punctate inner choroidopathy (PIC) was made based on the multiple hypopigmented spots in both eyes without evidence of intraocular inflammation elsewhere. The choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) in the patient’s left eye has been successfully treated with intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) therapy on a treat-and-extend regimen. During six years of follow-up to date, she has had several recurrences of PIC activity, and these episodes of inflammation have been treated successfully with intravitreal triamcinolone and oral prednisone. At her most recent visit, her visual acuity remained excellent at 20/20 OD and 20/30 OS.

DISCUSSION

Etiology/Epidemiology

Punctate inner choroidopathy (PIC) was first described by Watzke and colleagues in 1984 as an idiopathic inflammatory multifocal choroidopathy.[1] PIC predominantly affects otherwise healthy young women, usually between the second and fifth decades of life, with about 90% of reported cases between 18 to 40 years old. [2] Most patients are moderately myopic, and the degree of myopia is higher in PIC than in other white dot syndromes (e.g., diopter range of -3.25 to -10.0, with a mean diopter value of -4.6). [1,3]

Pathophysiology

The cause of PIC is largely unknown but thought to be inflammatory in nature.[4] Similar to other white dot syndromes, it is theorized that PIC is an autoimmune disease that arises in the context of an environmental stimulus. There is no known genetic component, as to date, no specific haplotype has been associated with PIC (unlike other white dot syndromes such as birdshot chorioretinitis).

PIC is considered among the “white dot syndromes,” a constellation of conditions whose clinical features include white fundus lesions in the choroid, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and retina. [4,5] These inflammatory lesions are thought to be due to antigen response from an unidentified culprit (e.g., Epstein-Barr virus) [6] and are similar in clinical appearance to presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome (POHS).[3] Histopathologic studies of PIC lesions have shown lymphocytic infiltration, supporting an inflammatory etiology. [7] PIC is sometimes considered within the spectrum of multifocal choroiditis (MFC), but patients with MFC are more prone to anterior chamber inflammation and/or vitritis. Furthermore, MFC typically has a more aggressive, chronic, and progressive course with worse visual prognosis compared to PIC.[4]

As illustrated in this case, the chorioretinal lesions in PIC are small, often about 100-200 microns in diameter, and are frequently seen in the posterior pole of both eyes.[4] As lesions progress over time, they often have increased depigmentation and atrophic scarring of the RPE.[1] This depigmentation and atrophic scarring can lead to the development of choroidal neovascular membranes (CNVMs), which occurs in up to 75% of patients with PIC.[4]

Signs/Symptoms

The most common presenting symptom for patients with PIC is a central or paracentral scotoma.[3] Other symptoms of macular disease, including blurred central vision or metamorphopsia are common, and symptoms of intraocular inflammation including floaters, photophobia, photopsias, or loss of peripheral vision are possible.[3] Visual prognosis with PIC is generally good, but permanent vision loss can occur with CNVMs and subretinal fibrosis.[3] In the original cohort of patients described by Watzke et al., the presenting visual acuity was 20/50 or better in most patients.[1] Patients often present with unilateral symptoms but on clinical examination demonstrate a bilateral disease process.

On clinical examination, the classic signs of PIC are small, white to yellow-gray lesions in the posterior pole that measure 100-200 microns in diameter.[4] These active lesions eventually develop into atrophic chorioretinal scars that may become increasingly pigmented with a “punched out” appearance. About a third of patients may develop CNVM and subsequent subretinal fibrosis, which is associated with a worse visual prognosis.[8]

Testing/Laboratory work-up

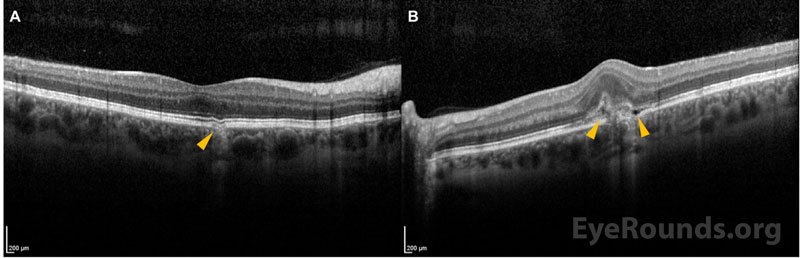

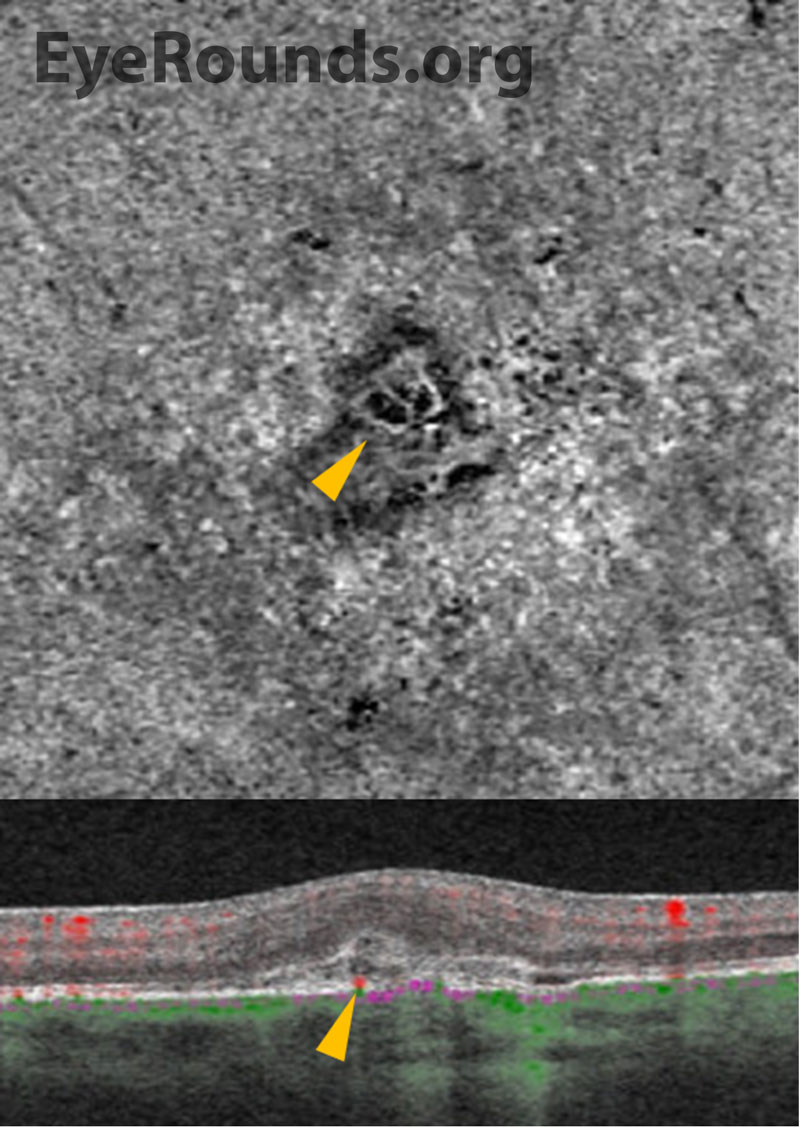

Multimodal ancillary testing and imaging have an important role in the diagnosis and evaluation of PIC. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is especially helpful to evaluate retinal and choroidal structural changes in PIC.[3,9] Clinically-active lesions are seen as disruptions of the RPE, with variable elevation and sub-RPE hyperreflectivity. Inner choroidal loss is a feature of PIC that may result in a focal choroidal excavation that is readily-visualized on OCT.[10,11] The disruption of Bruch’s membrane may predispose individuals to the development of a CNVM.

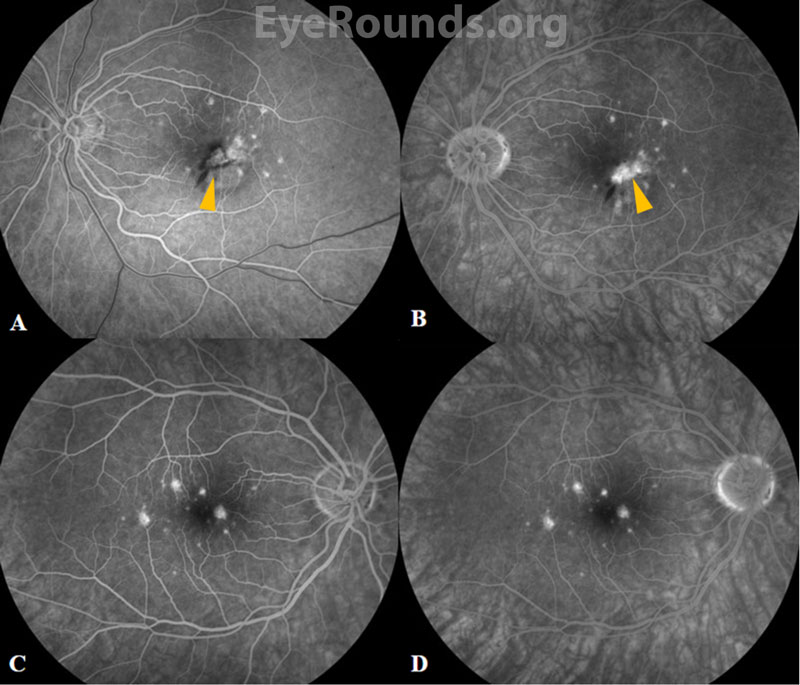

Fluorescein angiography (FA) reveals punctate hyperfluorescent lesions in early and late phases with variable leakage in late phases. As in this case, the lesions seen on FA can be more numerous than those appreciated on clinical examination. The presence of CNVM is demonstrated by a characteristic area of hypofluorescence surrounded by early hyperfluorescence.[1] Specifically, PIC-associated CNVMs were found to have a lace-like appearance of neovascularization on FA.[4]

A non-invasive modality that can also evaluate for choroidal vascular networks is OCT angiography (OCTA), which has been shown to have high sensitivity for detection of CNVMs when compared to FA.[12] In OCTA, an en face view of the outer-retina choriocapillaris slab can identify a vascular net with corresponding cross-sectional flow. OCTA is also clinically useful in assessing treatment response to anti-VEGF and can readily demonstrate involution of a CNVM.

Indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) is used less in clinical practice but can also be helpful in distinguishing PIC lesions. ICGA demonstrates hypofluorescence in the early and late stages along with midphases, consistent with decreased choroidal blood flow.[3]

Treatment/Guidelines

Treatment of PIC depends on the severity and clinical manifestations of disease activity. Observation is a reasonable approach for non-visually significant or fovea-sparing lesions. When there is vision threatening inflammation, treatment ranges from local therapy with intravitreal steroids to systemic steroid-sparing immunomodulatory therapy. The visual prognosis of PIC depends on the severity of disease and whether the clinical course is complicated by CNVM. Most patients, however, have a favorable prognosis with a final visual acuity of 20/40 or better.[4] While the overall prognosis is favorable, the activity and severity of the disease dictates the need for treatment. Acute chorioretinal lesions without CNVM may be treated initially with systemic corticosteroids, usually starting at 60-80 mg orally for 3-5 days followed by a taper that is dictated by the level of intraocular inflammation.[3] Local ocular steroid via peribulbar or intravitreal injection may also be effective.[3] In cases of progressive disease or recurrent activity, steroid-sparing treatment (e.g., mycophenolate mofetil) may be considered.[13]

CNVM is common in PIC and is most effectively treated with intravitreal anti-VEGF injections. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) and laser photocoagulation have also been reported to successfully treat CNVM in PIC, including in combination with anti-VEGF or intravitreal steroid therapy.[3,14]

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND ETIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

|

References

Patel P, Mansoor M, Han I. Punctate Inner Choroidopathy with Choroidal Neovascular Membrane. EyeRounds.org. January 9, 2023. Available from https://eyerounds.org/cases/336-PIC-with-CNVM.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.