Chief Complaint: Monocular esotropia

History of Present Illness (HPI)

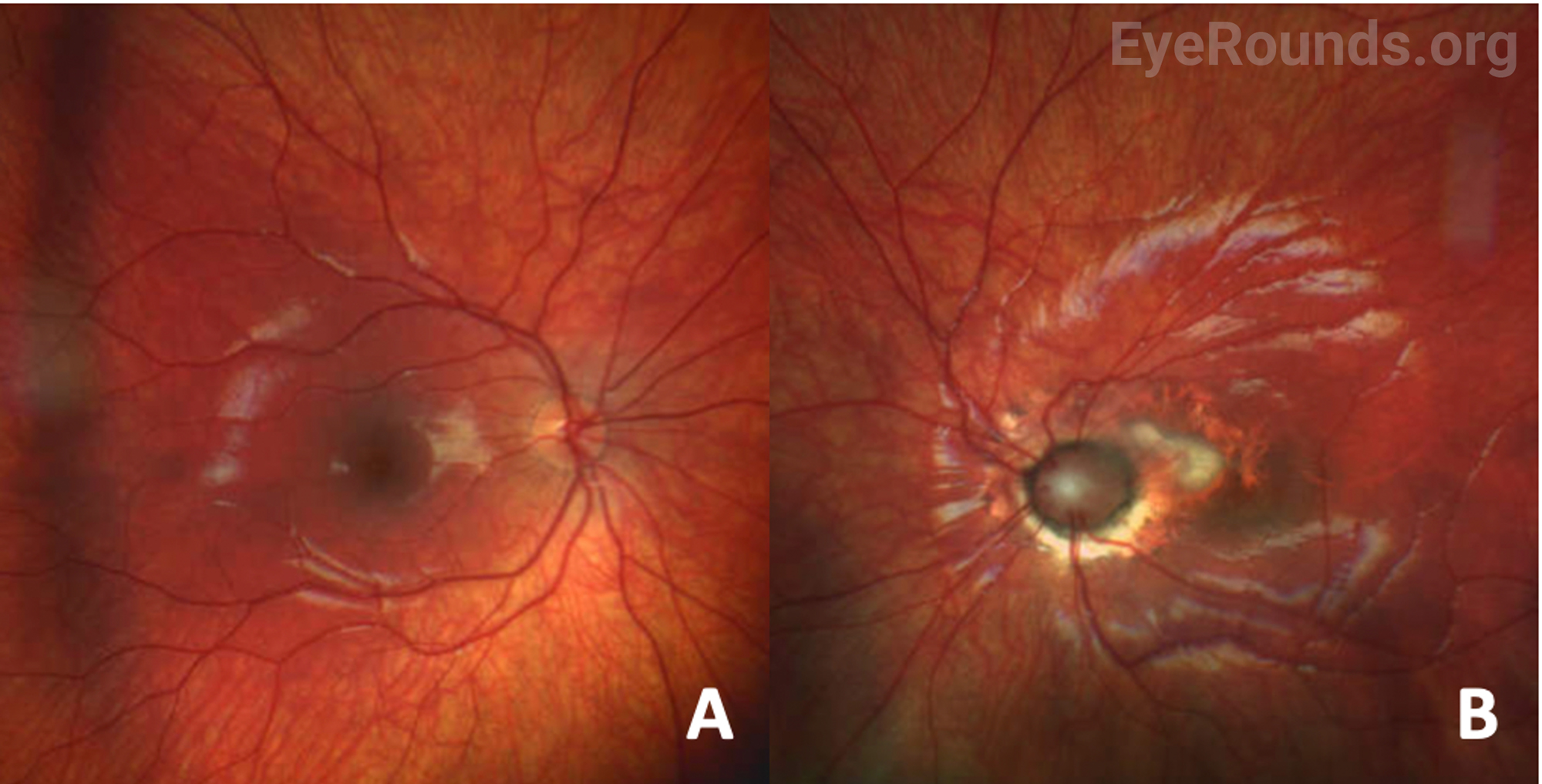

A 4-year-old girl was initially referred by her pediatrician to an outside ophthalmologist for decreased visual acuity and esotropia in the left eye. Her mother endorsed left eye crossing, poor balance, and speech delay, but the patient was otherwise meeting appropriate developmental milestones and was asymptomatic from an ocular standpoint. Initial exam by the outside ophthalmologist revealed an anomalous, funnel-shaped left optic nerve. The patient was ultimately referred to the University of Iowa for further evaluation.

Past Ocular History

Past Medical History

Medications

Allergies

Family History

Social History

Review of Systems

OCULAR EXAMINATION

| OD | OS | |

|---|---|---|

| Lids/Lashes | Normal | Normal |

| Conunctiva/Sclera | Clear and quiet | Clear and quiet |

| Cornea | Clear | Clear |

| Anterior Chamber | Deep and quiet | Deep and quiet |

| Iris | Normal architecture | Normal architecture |

| Lens | Clear | Clear |

| Anterior Vitreous | Normal | Normal |

| OD | OS | |

|---|---|---|

| Vitreous | Normal | Normal |

| Disc | Normal | Anomalous optic nerve, with enlargement and gliosis. Peripapillary elevation with white fibrosis |

| Macula | Normal | Foveal hypoplasia |

| Vessels | Normal | Normal |

| Periphery | Normal | Normal |

Differential Diagnosis

DIAGNOSIS: Morning Glory Disc Anomaly

CLINICAL COURSE

The patient’s exam findings were consistent with morning glory disc anomaly (MGDA) of the left eye. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with angiography (MRA) was overall unremarkable without evidence of basal encephalocele, cerebral vascular malformation, or cranial midline/chiasmal abnormalities. Genetic testing via chromosomal microarray did not demonstrate any causative genetic variant.

DISCUSSION

Etiology/Epidemiology

Morning glory disc anomaly (MGDA) is a congenital malformation of the optic nerve head, first reported Dr. Peter Kindler in 1970. He described a congenital, funnel-shaped, excavated, enlarged optic disc with central white-colored fibrous tissue, peripapillary pigmentary changes, and straight branches of retinal vessels emanating radially from the optic disc edge [1]. It is named due to its resemblance to the morning glory flower. Literature on the prevalence of MGDA is sparse. However, most reported cases are observed to be unilateral and sporadic [2]. Approximately 16% of cases are bilateral [3]. A 2015 cross-sectional study by Ceynowa et al. reviewed a population of 2.1 million Swedish individuals, and reported an estimated prevalence of 2.6 cases per 100,000 individuals [2]. Median age of diagnosis in this study was 0.5 years old (range 0-4 years) [2].

Pathophysiology

While the pathophysiology of MGDA is not well understood, this optic head malformation is thought to be secondary to abnormal differentiation of mesodermal issues. Specifically, incomplete closure of the posterior sclera and partial evolution of the lamina cribrosa have been largely implicated in these progressive optic nerve changes, allowing for anterior herniation of the disc and adjacent retina. Some element of neuroectodermal dysgenesis may contribute to the final phenotype of MGDA, as evidenced by the hallmark central gliosis and abnormal vascular pattern [4].

Histopathologic studies have provided additional insight into the underlying pathogenesis with reports of abnormalities of posterior pole structures, including peripapillary scleral ectasia (staphyloma), absence of lamina cribosa, absence of choroid, reduced number of ganglion cells and reduced retinal nerve fiber layer, absence of photoreceptors, glial tuft with psammoma bodies/glial cells/fibroblasts, attenuation of vessels, and hyperplastic persistent primary vitreous [5-6].

MGDA is usually sporadic. However, pathogenic variants in PAX6 gene have been identified in some families (7-8). Additionally, cavitary optic disc anomalies (CODA) – a disease spectrum including MGDA, megalopapilla, optic disc coloboma, and optic disc pit – are known to be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion through mutations in the MMP19 gene [9].

Signs/Symptoms

Presenting signs include decreased vision, strabismus, nystagmus, and/or leukocoria. Visual acuity in the MGDA eye is usually poor. One study of 12 MGDA eyes found a median best-corrected visual acuity of 20/300 (range 20/30 - hand motion) [2]. Strabismus (eso- or exodeviation are most common) may be present in up to 70% of eyes affected by MGDA (10). Afferent pupil defects and visual field deficits are common.

Fundus examination reveals a large, funnel-shaped excavation of the optic nerve head and peripapillary retina, with surrounding annular pigmentary changes. A central glial tuft with straight, narrow branches of retinal vessels radiating from the optic disc edge in a straight fashion resembles the morning glory flower [1]. In some instances, the adjacent macula can be involved in the larger area of excavation, a phenomenon known as “macular capture.” Other fundus findings may include subretinal fluid and retinal detachment.

Several case reports have described unilateral amaurotic episodes lasting 10-60 seconds in patients with known MGDA. Clinical dilated exams during these episodes describe temporary hyperemia, congestion of the normally excavated disc, and surrounding venous tortuosity. The proposed mechanism of heterotopic contractile tissue around the optic nerve and scleral canal explains these amaurotic episodes, as constriction of this tissue results in decreased venous flow and axonal block of the distal optic nerve [11]. Such symptoms are rare but should be investigated in the young patient presenting with frequent unilateral amaurosis.

Optic nerve coloboma may present similarly to MGDA and should be distinguished as they both have different systemic associations, described below. Fundus examination may also help distinguish MGDA and optic nerve coloboma, the latter of which tends to have an inferior white excavation extending into the choroid and retina while sparing the superior rim [12]. Optic nerve coloboma can be associated with CHARGE syndrome, which consists of coloboma of the eye, heart defects, choanal atresia, growth retardation, genitourinary and ear abnormalities.

Testing/Laboratory work-up

In addition to a thorough eye examination, including a fundus exam, additional ancillary testing may be helpful in determining a diagnosis of MGDA as well as assessing the extent of involvement. OCT is helpful in identifying the primary disc anomaly as well as associated findings, including intra/subretinal fluid, retinal holes, or peripapillary retinal detachments. B-scan echography can aid in further characterization of MGDA findings, including optic nerve excavation, central glial tuft, microphthalmos, and retinal tissue overhanging the posterior scleral staphyloma or “overhang sign” [13]. Furthermore, echography may help estimate the risk of retinal detachment. For example, in a retrospective review of 249 Chinese children, the ratio of cavitary depth to axial length greater than or equal to 0.25 was associated with an increased risk of retinal detachment (OR, 2.101; 95% CI 1.47-3.0) [14].

MRI/MRA should be obtained to evaluate for associated systemic vasculopathies (i.e. Moya-Moya) and midline central nervous system deformities, as outlined below.

Treatment/Management

In patients with MGDA, the first steps in management involve correcting refractive errors with glasses to improve acuity (as good as possible), address underlying amblyopia, and physically protect the better-seeing eye. Patching should be attempted to treat amblyopia but may be unsuccessful due to the underlying organic abnormality.

Several clinical associations commonly co-occur with MGDA, which require further evaluation. Retinal detachments are common in individuals with MGDA, with up to 14% of patients developing a detachment in 5 years of presentation and 33% in 10 years [15]. Successful retinal detachment repair has been reported with visual improvement for certain patients. Recurrence of retinal detachment is not unlikely [16]. Thus, patients with MGDA should have regular fundus examination to monitor for retinal detachments.

MGDA is also associated with midline facial and central nervous system abnormalities. These include cleft lip and palate, basal encephalocele (protrusion of neural tissue through a skull defect – trans-sphenoidal type), agenesis of corpus callosum, Chiari type 1 malformation, and pituitary gland dysgenesis [12]. As described above, these patients should undergo MRI to evaluate for presence of these defects. Subsequent endocrine workup may be indicated.

A potentially life-threatening association with MGDA is cerebrovascular abnormalities such as Moya-Moya disease, which is characterized by abnormally narrow cerebral vasculature resulting in ischemia, hemorrhage, seizure, intellectual impairment, or transient ischemic attacks. While the exact prevalence is unknown, Moya-Moya has been observed in up to 45% of patients with MGDA as reported in a small retrospective case series [17]. MRI/MRA or computed tomography angiography (CTA) is recommended as part of the work-up to evaluate for this cerebrovascular abnormality.

PHACE syndrome (posterior fossa malformation, large facial hemangioma, arterial anomalies, cardiac anomalies, eye anomalies) has also been reported in patients with MGDA [20].

EPIDEMIOLOGY OR ETIOLOGY

|

DIAGNOSIS

|

SYMPTOMS/SIGNS

|

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

|

Baksh BS, Silverman JIM, Dumitrescu AV. Morning Glory Disc Anomaly . EyeRounds.org. Posted January 22, 2024; Available from https://EyeRounds.org/cases/354-Morning-Glory-Disc-Anomaly.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.