Dominant Optic Atrophy:

47-year-old female with chronic, mildly subnormal vision

August 21, 2005, revised Feb. 21, 2006

Download pdfChief Complaint: Chronic, stable, mildly diminished vision

History of Present Illness: 47-year-old Caucasian female with the presumptive diagnosis of cone dystrophy who was referred to the Retina Clinic at the University of Iowa for further evaluation of chronic, mildly diminished visual acuity and dyschromatopsia. The patient reported that her vision has never been correctable to 20/20. The best visual acuity she remembers having is 20/30 in the left eye.

Ocular History: She was diagnosed with amblyopia (known commonly as "lazy eye") in the right eye as a child and underwent a trial of patching at age ten. She is anisometropic (a significantly different spectacle prescription in each eye) and her vision has always been worse in the right eye, presumably due to amblyopia.

Medical History: None.

Medications: She takes no medications on a regular basis. She has never taken hydroxychloroquine or antipsychotic medications (medicines that can in some patients injure the macula and cause decreased central vision).

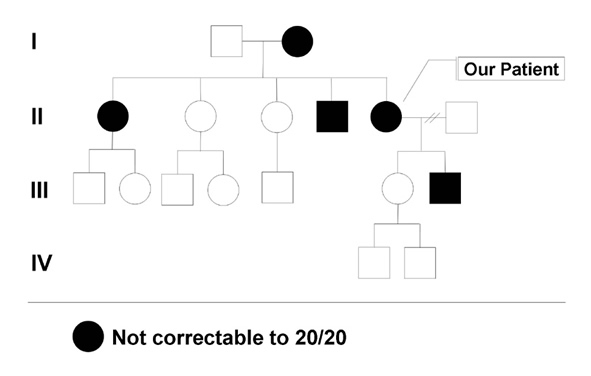

Family History: She has several family members with mildly subnormal vision. Her mother, brother, sister, and son all have mildly reduced vision, in the range of 20/30 to 20/50 (see Figure 1). All of the affected family members are able to drive.

Social History: She works as a clerk. Her social history is otherwise unremarkable.

|

OCULAR EXAM:

- Visual Acuity (with corrective lenses):

- Right eye -- 20/70; Left eye -- 20/40

- Current spectacle correction:

- Right eye: -0.75 +2.50 x 037

- Left eye: -3.00 sphere

- Manifest Refraction (MRx) imrpoves the acuity of the right eye to 20/60 while the left eye remains unchanged

- Motility: Orthophoric (normally aligned) in primary gaze; Versions (ability to move the eye in all directions) full.

- Intra-ocular pressure: Right eye --12 mmHg; Left eye --14 mmHg.

- Pupils: Normal in both eyes. No relative afferent pupillary defect.

- External and anterior segment examination: Normal in both eyes.

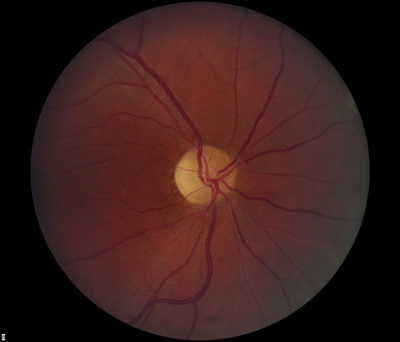

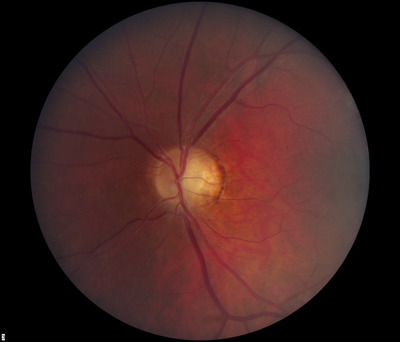

- Dilated fundus exam: There was optic disc pallor, predominantly temporal, in both eyes. Peripapillary atrophy and grey temporal crescent were noted in the left eye (see Figure 2). The macula, vessels, and periphery were normal in both eyes.

- Ishihara plates: 2/14 OD, 3/14 OS

- Nagel anomaloscope: protanomalous match

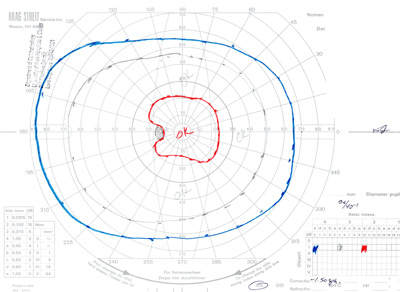

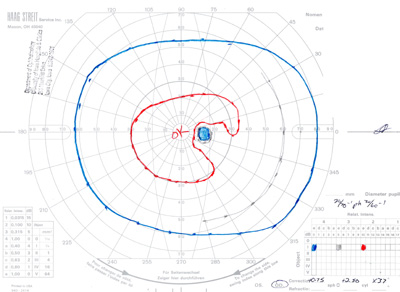

- Goldmann Visual Field testing (see Figure 3):

- Right eye -- baring of blind spot with mildly constricted I2e isopter

- Left eye -- constricted I2e isopter

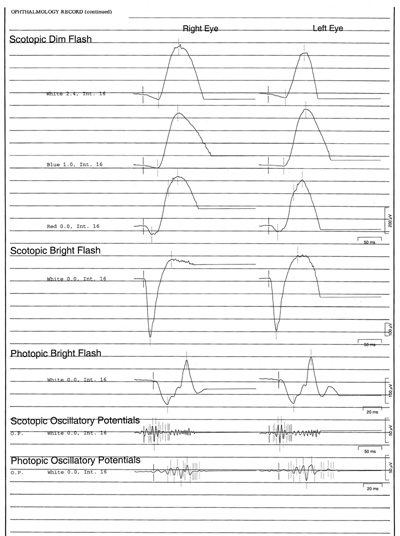

- Electroretinogram (ERG): scotopic bright flash 589 microvolts in the right eye, 572 microvolts left eye; scotopic dim flash 405 microvolts right eye, 340 microvolts left eye, photopic bright flash 180 microvolts right eye, 185 microvolts left eye (see ERG waveforms in Figure 4).

|

|

|

Course: A blood sample for molecular studies was obtained. The clinical and genetic features of autosomal dominant optic atrophy (the most likely diagnosis) were discussed. More information will follow when results of the genetic testing are complete. The patient returned to the care of her local eye doctor.

Discussion: Autosomal dominant optic atrophy or Dominant Optic Atrophy (DOA) is, as suggested by the name, an autosomal dominantly inherited optic neuropathy characterized by subnormal visual acuity, visual field abnormalities, and optic nerve pallor in the setting of an otherwise normal eye exam. Family history is often positive, but because of variable expressivity, mildly affected family members may go undiagnosed ( e.g., incomplete penetrance). Furthermore, This incomplete penetrance can result in an inheritance pattern that is suggestive of autosomal recesssive or X-linked disease. The penetrance of Dominant Optic Atrophy has been estimated to be as high as 100% ( Thiselton 2002) and as low as 43% ( Toomes 2001), however these percentages appear to depend on the specific mutation.

Vision loss typically begins as the affected individual reaches school age. The onset and progression are insidious – most patients are unable to identify a precise age of onset. As many as 50% of patients with Dominant Optic Atrophy experience a progressive loss of vision with advancing age. Dyschromatopsia (color blindness) is frequently present but its manifestations are variable. Initially, Dominant Optic Atrophy was thought to be most closely associated with blue color vision deficits ( Kline 1979), but more recent studies have demonstrated that mixed color deficits are most common (81%) ( Votruba 1998).

Optic disc pallor is one of the defining characteristics of Dominant Optic Atropy. About half of the affected individuals have disc pallor that is limited to the temporal side of the disk while the remaining patients have diffuse disc pallor. The degree of pallor tends to correlate with the severity of vision loss. In a recent series of patients with proven OPA1 mutations (see below), 69% had peripapillary atrophy, 31% had a temporal grey crescent, and 48% had a cup to disc ratio of >0.5 ( Votruba 2003). The most common visual field defects are central or cecocentral scotomas, although altitudinal defects also have been described in patients with documented OPA1 mutations ( Brown 1997). Histopathologic studies have shown loss of retinal ganglion cells, especially in the papillomacular bundle, and diffuse atrophic changes of the optic nerve (Johnston 1979).

The vast majority of Dominant Optic Atrophy cases are caused by mutations in the gene OPA1, located on chromosome 3q ( Votruba 2004). OPA1 is most abundantly expressed in the retina and brain ( Votruba 2004). Over 70 different variations in OPA1 have been observed in patients with a DOA phenotype ( Votruba 2004). Genetic testing for mutations in OPA1 will soon be available through the Carver Laboratory for Molecular Diagnosis (www.carverlab.org), a nonprofit laboratory dedicated to providing molecular diagnostic studies for heritable eye conditions. Other sources for genetic testing of DOA can be found at www.genetests.org. A smaller fraction of patients with DOA have been linked to OPA4 on chromosome 18 ( Kerrison 1999). X-linked optic atrophy has been linked to OPA2 ( Assink 1997), while mutations in OPA3 are associated with at least one type of autosomal recessive optic atrophy ( Anikster 2001).

Summary: Dominant Optic Atrophy (DOA)

GENERAL

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT

|

Differential Diagnoses for Dominant Optic Atrophy

-

Normal tension glaucoma

disk cupping, usually not familial, more rapidly progressive than DOA

-

Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON)

In LHON, the vision is initially normal and drops suddenly and catastrophically (usually 20/400 or worse) in one eye at a time. The second eye is typically affected within weeks or months of the first eye but the two eyes are rarely affected at the same time. There may be a positive family history but unlike dominant disease, the affected individuals are always connected through females. That is, males never transmit the disease to their descendents.

-

Compressive optic neuropathy

Less likely to be bilateral than DOA, usually more rapidly progressive, patients have a history of normal vision in the past, less likely to have a positive family history of a similar disease (unless it is in the context of neurofibromatosis) neuroimaging is diagnostic

-

Infiltrative or inflammatory optic neuropathy

Usually more rapidly progressive, patients have a history of normal vision in the past, less likely to have a positive family history of a similar disease, disks show more evidence of swelling than atrophy, there may be other inflammatory stigmata elsewhere in the fundus

-

Toxic or nutritional optic neuropathy

History of exposure to a toxin (especially large amounts of alcohol) and or an unusual diet (e.g., tea and toast). In addition, usually more rapidly progressive than DOA, patients have a history of normal vision in the past and are less likely to have a positive family history of a similar disease than patients with DOA.

-

Optic nerve hypoplasia (septo-optic dysplasia)

Disks are smaller than normal and may exhibit a "double ring sign". Septo-optic dysplasia and other central nervous system abnormalities are present in up to 75% of cases which can be seen on neuroimaging. It is important to diagnose septo-optic dysplasia because there are frequently significant endocrine abnormalities associated with this congenital malformation. Unlikely to have a positive family history of a similar disease.

|

|

| Septo-Optic Dysplasia | Double Ring Sign |

References

- Alward WL. The OPA1 gene and optic neuropathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003 Jan;87(1):2-3.

- Anikster Y, Kleta R, Shaag A, Gahl WA, Elpeleg O. Type III 3-methylglutaconic aciduria (optic atrophy plus syndrome, or Costeff optic atrophy syndrome): identification of the OPA3 gene and its founder mutation in Iraqi Jews. Am J Hum Genet. 2001 Dec;69(6):1218-24. Epub 2001 Oct 19.

- Assink JJ, Tijmes NT, ten Brink JB, Oostra RJ, Riemslag FC, de Jong PT, Bergen AA. A gene for X-linked optic atrophy is closely linked to the Xp11.4-Xp11.2 region of the X chromosome. Am J Hum Genet. 1997 Oct;61(4):934-9.

- Brown J Jr, Fingert JH, Taylor CM, Lake M, Sheffield VC, Stone EM. Clinical and genetic analysis of a family affected with dominant optic atrophy (OPA1). Arch Ophthalmol. 1997 Jan;115(1):95-9. Erratum in: Arch Ophthalmol 1997 May;115(5):663.

- Jacobson DM, Stone EM. Difficulty differentiating Leber's from dominant optic neuropathy in a patient with remote visual loss. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1991 Sep;11(3):152-7.

- Johnston PB, Gaster RN, Smith VC, Tripathi RC. A clinicopathologic study of autosomal dominant optic atrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979 Nov;88(5):868-75.

- Kerrison JB, Arnould VJ, Ferraz Sallum JM, Vagefi MR, Barmada MM, Li Y, Zhu D, Maumenee IH. Genetic heterogeneity of dominant optic atrophy, Kjer type: Identification of a second locus on chromosome 18q12.2-12.3. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999 Jun;117(6):805-10.

- Kline LB, Glaser JS. Dominant optic atrophy. The clinical profile. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979 Sep;97(9):1680-6.

- Newman NJ, Biousse V. Hereditary optic neuropathies. Eye. 2004 Nov;18(11):1144-60

- Thiselton DL, Alexander C, Taanman JW, Brooks S, Rosenberg T, Eiberg H, Andreasson S, Van Regemorter N, Munier FL, Moore AT, Bhattacharya SS, Votruba M. A comprehensive survey of mutations in the OPA1 gene in patients with autosomal dominant optic atrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002 Jun;43(6):1715-24.

- Toomes C, Marchbank NJ, Mackey DA, Craig JE, Newbury-Ecob RA, Bennett CP, Vize CJ, Desai SP, Black GC, Patel N, Teimory M, Markham AF, Inglehearn CF, Churchill AJ. Spectrum, frequency and penetrance of OPA1 mutations in dominant optic atrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2001 Jun 15;10(13):1369-78.

- Votruba M, Thiselton D, Bhattacharya SS. Optic disc morphology of patients with OPA1 autosomal dominant optic atrophy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003 Jan;87(1):48-53.

- Votruba M. Molecular genetic basis of primary inherited optic neuropathies. Eye. 2004 Nov;18(11):1126-32.

- Votruba M, Fitzke FW, Holder GE, Carter A, Bhattacharya SS, Moore AT. Clinical features in affected individuals from 21 pedigrees with dominant optic atrophy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998 Mar;116(3):351-8.

Suggested citation format: Howard JG, Stone EM: Dominant Optic Atrophy: 47-year-old female with chronic, mildly subnormal vision. EyeRounds.org. August 21, 2005, revised Feb. 21, 2006; Available from: http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/47-AutosomalDominantOpticAtrophy.htm.