Chief Complaint: Referred for evaluation of macular drusen, OU, in 30-year-old female patient.

History of Present Illness: Patient was seen in an on call clinic for evaluation after accidental peri-orbital exposure to rubbing alcohol. The patient was treated for mild chemical conjunctivitis. Incidentally, fundus examination revealed macular drusen. The patient was scheduled to be seen at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics (UIHC) for further evaluation of asymptomatic drusen in a 30-year-old patient. Her first evaluations in our clinic were in the early 1990's. With the exception of her recent chemical exposure, the patient reported no particular visual complaints at that time.

Ocular History: Mild convergence insufficiency. No eye surgery nor eye trauma.

Medical History: Occasional migraine headaches and mild gastric reflux disease.

Medications: Acetomenophen PRN for headache.

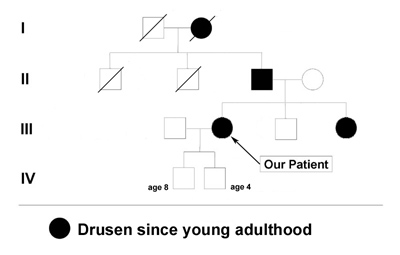

Family and Social History: The patient reports that her father, sister, and grandmother have all been told that they have drusen or "macular degeneration" since early adulthood (see Figure 1). Her two sons (ages 4 and 8) do not have any visual symptoms and have not had a retina evaluation. She is concerned with the term "macular degeneration" and wonders about her risks and those of her children for an inherited retinal disease.

|

|

|

|

|

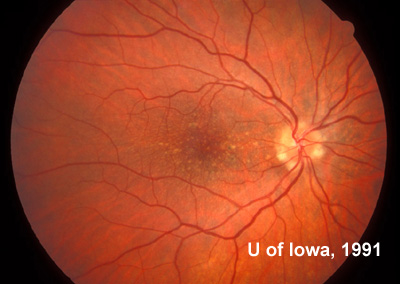

Course: In this young patient with a radiating pattern of drusen in both eyes and an autosomal dominant family history of similar findings, a diagnosis of a familial dominant drusen is likely. Specifically, Malattia Leventinese seemed the most probable diagnosis. In the 1990's when this patient was first seen in the retina clinic at the University of Iowa molecular testing was not an option. Baseline fundus photographs were taken for future comparison and the diagnosis was discussed with the patient. Because of the potential risk for further degeneration or the small possibility of developing choroidal neovascular membranes (CNVM), the patient was instructed in the use of an Amsler grid and scheduled to return for repeat evaluation every 1-2 years (or sooner, if there were any change in her symptoms).

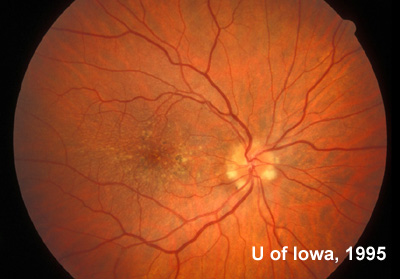

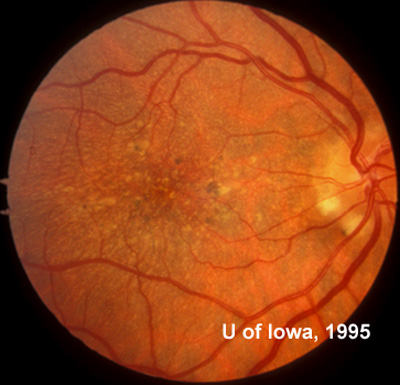

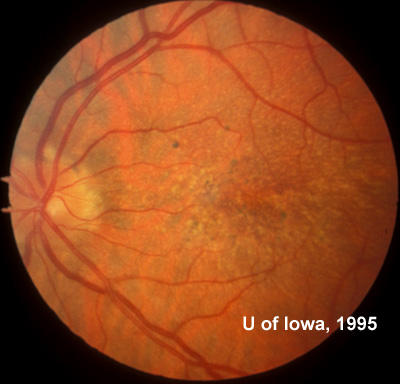

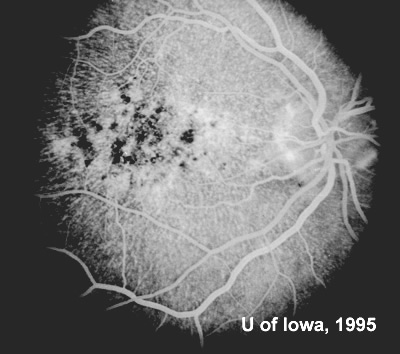

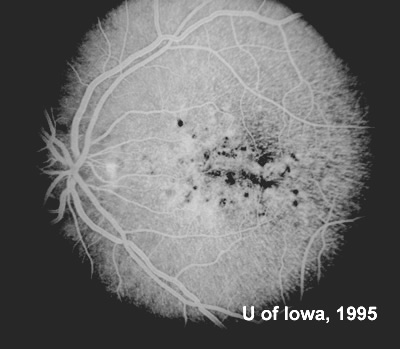

At follow-up visits in 1995 and 1996, the patient reported some mild metamorphopsia in the left eye. Amsler grid evaluation revealed "bumps" in the horizontal lines of the grid just superior to fixation. Visual acuity was 20/20 -2 in the right eye and 20/25 + in the left eye. Repeat examination at this time revealed an increase in retinal pigment epithelial changes, some confluent drusen, and some atrophic changes. However, there was no clinical evidence of CNVM (See Figure 3). Fluorescein angiography (FFA) was performed and confirmed that there was no neovascular membrane (see Figure 4).

|

|

|

|

|

|

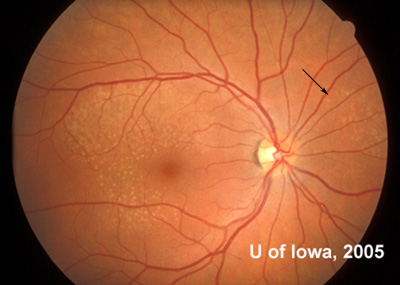

In the years that followed, the patient did have some mild further decrease in vision due to progressive RPE atrophy in the macula of both eyes. Fundas photos were taken again recently (see progressive photos in Figure 5). The patient has never developed any evidence of CNVM in either eye. Visual acuity at last evaluation was 20/40- in the right eye and 20/30- in the left eye. When genetic testing for Malattia Leventinese became available, a blood sample was taken at the patient's request for genetic analysis. The patient was confirmed positive for a single mutation (Arg345Trp) in the fibulin 3 gene on chromosome 2p (FBLN3). This gene is also known as the epidermal growth factor (EGF)-containing fibrillin-like extracellular matrix protein-1 (EFEMP1). With this confirmed information, the patient was able to receive precise genetic counseling for the potential risks her two sons and other future progeny may face for Malattia Leventinese.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The term familial drusen (or familial dominant drusen) is used to describe a group of visual conditions in which radiating drusen and a type of macular degeneration that occurs in very young patients. Two specific conditions were initially described in the literature as separate entities. In 1899 Robert Walter Doyne, an ophthalmologist at the time in Oxford, England, first described a clinical condition meeting this description. The rare condition became known as Doyne honeycomb retinal dystrophy (DHRD). In 1925, a strikingly similar condition was defined in a number of individuals from a family in the Leventine Valley of southern Switzerland which thereafter became known as Malattia Leventinese (or "the malady of the Leventine valley"). Work continued throughout the latter half of the 20th century to better define each of these diseases independent from one another. In 1999 it was suggested that the two disorders most likely represent variable expression of the same disease. A single defect in the gene that encodes for the protein fibulin 3 (EFEMP1) was demonstrated to exist in individuals with a defined clinical diagnosis of both Malattia Leventinese and DHRD (Stone, 1999 and Tarttelin, 2001). Most ophthalmologists now accept the two entities as the same malady.

There are other cases of what are currently simply called "familial drusen" for which the inheritance pattern is not defined, but Malattia Leventinese is a defined entity which is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. The hallmark finding of this retinal degeneration is the presence of yellow-white deposits in the RPE (drusen) in a radiating pattern throughout the macula that are present early in life (often by the second decade). These elongated drusen may also be found outside the arcades, especially nasal to the disc which is unusual in other types of macular degeneration (see Figure 6). These drusen may also be found in some patients in a peripapillary pattern or on the margin of the disc itself. If fluorescein angiography is performed, it will highlight the extensive drusen and atrophy at the posterior pole. Despite the impressive drusen seen on exam, the vision for most patients with Malattia Leventinese remains fairly good for many years. Indeed, many patients remain asymptomatic into the fourth decade of life before they notice some decrease in vision or metamorphopsia. As the degeneration progresses, however, confluence of drusen and RPE atrophy can lead to further visual loss. Some patients may develop CNVM which can dramatically decrease vision.

|

Though there is no direct treatment at this time to prevent progression of Malattia Leventinese, precise molecular diagnosis may be desired both by patients and clinicians (see www.carverlab.org). As research progresses toward potential treatment for this and other inherited diseases, knowlege of the molecular diagnosis will be important in counseling patients and their families on prognosis and future treatment options. Of additional importance, the macular changes in Malattia Leventinese are very similar to the changes found in age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Likewise, mutation in various fibulin genes have recently been directly associated with AMD. As a result, further study of Malattia Leventinese may have ramifications that extend to a much larger patient population.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT

|

Graff JM, Stone EM. Malattia Leventinese (Familial Dominant Drusen): 30-year-old female with drusen. EyeRounds.org. February 12, 2008; Available from: http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/48-Malattia-Leventinese-Familial-Dominant-Drusen.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.