Chief Complaint: 6 day-old male patient is referred for evaluation of "fleshy masses" on the lateral aspect of both corneas.

History of Present Illness: The patient was born at 36 weeks gestation and was delivered by normal spontaneous vaginal delivery (NSVD). He had mild neonatal jaundice that did not require treatment and was improving. Shortly after delivery, he was noted to have bilateral "fleshy masses" on the corneas and an irregular right upper eyelid. This prompted initial referral to the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics Pediatric Ophthalmology division for evaluation.

(This patient was first seen here in June of 2002 and has been followed and cared for since that time. The description of his initial presentation is here provided and his course of care is described in the Course section of this case presentation).

Past Ocular History: This was the patient's first presentation for eye care.

Medical History: Normal delivery at 36 weeks gestation to a 26-year-old mother in her fourth pregnancy whose first three pregnancies were lost to spontaneous abortion (G4 P1 SAB3). The patient had mild neonatal jaundice not requiring treatment. No other medical issues noted to date and infancy has been otherwise normal with achievement developmental milestones.

Medications: None

Family History: Noncontributory. No family history of facial syndromes or ocular conditions.

Social History: Newborn infant lives at home with his parents.

|

Course: The constellation of bilateral limbal dermoids, eyelid coloboma, and preauricular skin tags was consistent with a diagnosis of Goldenhar syndrome. The limbal dermoids did not obstruct the visual axis and the right upper eyelid coloboma did not prevent corneal protection with lid closure. As such, the patient's ocular condition did not require urgent intervention in the first weeks of life. We invited the involvement of the Medical Genetics team to evaluate the patient and aid in additional work-up for more serious malformations that can occur in the oculo-auriculo-vertebral spectrum. The patient was scheduled to return to our clinic within 1-2 months and to be followed closely for any change in visual cues or refraction during the ensuing months.

Evaluation was carried out by the Pediatric and Medical Genetics teams at the University of Iowa. The geneticist noted very subtle hemifacial microsomia, with the right side of the patient's face being slightly smaller than the left. He had no clefting of the lip or palate. Audiology tests on two different occasions were normal. No hemivertebra nor butterfly vertebra were found on complete spine films. MRI of the brain was completely normal. Renal ultrasound at birth was normal. Evaluation by a cardiologist revealed a faint (1/6) vibratory murmur at the cardiac apex which was felt to be benign. Electrocardiogram (EKG) and chest x-ray were within normal limits for age. Peripheral blood analysis revealed a normal 46,XY karyotype.

The patient was followed closely in our clinic during this time. Early cycloplegic refraction revealed significant astigmatism in both eyes:

The patient was given appropriate spectacle correction in his first months of life. The patient continued to be central, steady, and maintained (CSM) in fixation in each eye independently throughout the first several months of life and tolerated his glasses well. By the age of 10 months, the mother began to notice that the eyelid in the right eye would "hang up" on the limbal dermoid. Several times, the mother would find the toddler asleep with the right eye incompletely closed. Given the exposure of the right eye, it was determined to proceed with removal of the right limbal dermoid. The mass was excised primarily with a maximal depth of dissection of 60%. No lamellar keratoplasty was required.

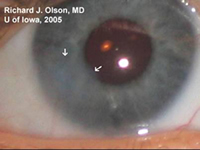

The patient recovered well from this procedure and healed promptly with minimal corneal scar and no recurrence of limbal dermoid in the 2 years that followed. Visual acuity evaulation has consistently shown him to be central, steady, and maintained (CSM) in both eyes with good fixation and following (F&F) in each eye independently. The corneal shape has stabilized on the right side since the surgery and there is still significant astigmatism. The astigmatism in the left eye, without any intervention, has settled down significantly compared to early measurements. Refraction at follow-up in October of 2005 (age 3 yr 4/12 mo) was :

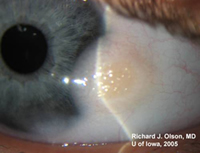

The limbal dermoid on the left side has not changed in size, does not threaten the visual axis and does not inhibit closure of the lids (see Figure 2B and 3). The induced astigmatism from this dermoid is small and readily corrected with spectacles. The left eye continues to be the patient's favored eye, but there is no evidence of amblyopia. Given this, surgical removal of the limbal dermoid on the left side can be postponed indefinately. The lid coloboma (see Figure 3) does not result in corneal exposure and will not require surgery. Small skin tags on the right cheek and preauricular area (see Figure 2C) can be removed, if desired, for cosmesis as the child grows.

| A: Right eye 2 years after removal of large limbal dermoid (see Figure 1). Residual corneal haze (arrows) indicates the former border of the excised dermoid. | B: Left eye slit lamp view shows the elevated, fatty appearance of this limbal dermoid. Hair may be seen in these fatty tumors as well. | C: Preauricular skin tag, right ear. The ear itself has no deformity or microtia. |

|

|

|

|

Goldenhar syndrome (also known as oculo-auriculo-vertebral spectrum or hemifacial microsmia) is a developmental malformation of the first and second branchial arches. The constellation of abnormalities was first described by Dr. Maurice Goldenhar (Goldenhar, 1952) in a pair of monozygotic twins with epibulbar dermoids, auricular appendages, malformations of the auricle, and hemifacial microsomia. This entity was further described as the oculo-auriculo-vertebral spectrum ten years later (Gorlin, 1963). Given the heterogeneous and variable presentation of this condition, it is probably best to describe it as a spectrum of dysmorphogenesis, the main characteristics of which are 1) epibulbar dermoids, 2) auricular appendages or malformations and 3) skeletal anomalies (including hemifacial microsomia and/or hemivertebra or butterfly vertebra. Other associated facial defects can include microphthalmos, strabismus, eyelid coloboma, preauricular fistulas, macrostomia, maxillary and mandibular hypoplasia, cleft palate, cleft lip, and middle and/or inner ear deformities contributing to hearing loss. In the majority of cases, only one side of the body is affected (interestingly, the right side is usually the more severely affected). Some affected individuals may have congenital heart defects, renal defects (hypoplasia or agenesis), or central nervous sytem (CNS) malformations (intracranial lipomas, hydrocephalus, cranial nerve dysgenesis and mental retardation). No formal minimal diagnostic criteria have been widely accepted, though some have been suggested (Tasse et al, 2005).

The case we present here is certainly a more mild variation of the Goldenhar condition. As was the case with this child, Goldenhar syndrome is generally believed to be a spontaneous malformation in utero, without a predictable inheritance pattern. No isolated genetic defect has been confirmed as responsible for the syndrome, though there are small studies that support both autosomal dominant (Beck et al 2005, Stoll et al 1998, Singer et al 1994) and autosomal recessive (Cohen, 2000) inheritance pattern in some families and underlying gene defects have been theorized. There has been no proven association of Goldenhar syndrome with any maternal infection, medication or other insult. Incidence is between 1 in 3,000 and 1 in 5,600 live births. Males are more affected than females in a 2:1 ratio.

Treatment for the disease varies according to the severity of manifestation. With regards to the role of the ophthalmologist, treatment is directed first at strong amblyogenic risks (including obstruction of the visual axis, severe astigmatism, or strabismus), second at ocular exposure (due to large lid coloboma or limbal dermoid preventing lid closure), and third at working with craniofacial surgeons in cases severe microsomia that requires reconstruction of the upper face. Systemic treatment may be indicated for cardiac, renal, or CNS malformations.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMSThe syndrome is almost always diagnosed early in life, before there is any complaint of symptoms by the infant patient. Symptoms could include:

|

TREATMENT

|

Graff JM, Bhola R, Olson RJ: Goldenhar Syndrome (Oculo-Auriculo-Vertebral Spectrum): 6 day-old male with limbal dermoids. Eyerounds.org. March 31, 2006; Available from: http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/55-GoldenharSyndromeLimbalDermoidColoboma.htm.

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.