Chief Complaint: 72-year-old female with decreased vision referred for "corneal ulcer" in the right eye (OD).

History of Present Illness: The patient is a monocular female who was referred for evaluation and treatment of a corneal ulcer in her right eye.

Past Ocular History: Extensive prior ocular issues, including primary open angle glaucoma, neurotrophic keratitis OD, and multiple bouts of herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis in both eyes (OU). Surgically, she had undergone cataract extraction in both eyes (posterior chamber intraocular lens implant in the right eye and aphakic in the left eye) and penetrating keratoplasty in the right eye in 1996. She underwent three penetrating keratoplasties in the left eye (OS) in 1997, 1998 and 2000, and eventually required an evisceration for a blind, painful eye in 2003.

Medical History: Significant for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypothyroidism, asthma, gastroesophageal reflux disease, hiatal hernia, osteoporosis, syncope, elevated cholesterol, skin dermoids and a history of myocardial infarction status post coronary artery bypass grafting x 4 vessels.

Medications (OD only): brimonidine P 0.15% BID, latanoprost 0.005% QHS, and sodium chloride 5% QID and valacyclovir by mouth, 500mg BID. The referring doctor had recently placed her on hourly moxifloxacin drops.

Family History: Noncontributory

Social History: No alcohol use. Quit smoking in 1980’s.

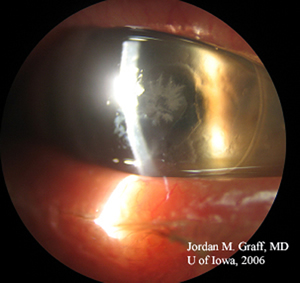

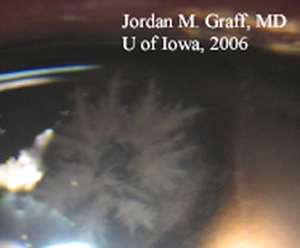

| 1A: Crystalline infiltrate centrally in corneal graft, OD. | 1B: Magnified view of crystalline pattern, OD. |

|

|

Course: The patient was admitted to the hospital, placed on vancomycin (25mg/ml) drops Q1 hour, moxifloxacin drops Q1 hour, valacyclovir 1000mg po BID and monitored closely. The epithelial defect continued to enlarge over the next 2 days of inpatient treatment with no improvement. The antibiotics were tapered to q2h because of concern with toxicity and bandage contact lens was applied to the surface of the cornea. The epithelial defect slowly healed over the next several days, but the infiltrates persisted. The patient ultimately required a repeat penetrating corneal transplant. The patient was seen in follow-up three weeks prior to this publication. The new graft remained clear with no evidence of recurrent infection.

Discussion: Infectious crystalline keratopathy (ICK) was first described in the 1980's as a unique and distinctive clinical entity characterized by white, branching, crystalline, opacities within the corneal stroma and little or no associated inflammatory response (Gorovoy MS 1983, Dunn S 1985, and Meisler DM 1984). A sharply demarcated, snowflake-like stromal opacity on a background of clear, uninflammed corneal graft is the classic presentation (see Figure 1B), though variations on this theme are common.

Though ICK is most commonly associated with Streptococcus species (α-hemolytic Streptococcus is the most common cause), the clinical entity described above may be caused by a variety of organisms. There are case reports of clinical ICK from culture-proven S. pneumoniae, Haemophilus species, Peptostreptococcus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, G. Haemolysans as well Candida and Alternaria fungi. In this case, culture of corneal scrapings revealed heavy growth of Group G, β-hemolytic Streptococcus.

ICK occurs more commonly in corneal grafts or otherwise immunocompromised corneas. The most common risk factors for infectious crystalline keratopathy include history of penetrating keratoplasy (usually many months after transplant), corticosteroid use, and contact lens wear. It is likely that gram-positive cocci from the periocular skin or conjunctiva gain access to the stroma by tracking along suture lines or through micro-defects in the corneal epithelium. As opposed to many other bacterial infections of the cornea, the epithelium in IKC may appear intact and there is a paucity of inflammatory infiltrate. Some have suggested that the bacterial colonies that cause ICK are less pathogenic, allowing them to invade and replicate within the stroma without inciting much response in the host.

Though classic ICK is very distinctive, proper organism identification still requires isolation of the offending organism by deep corneal scrapings or corneal biopsy (Khater, 1997). Histopathology of corneal biopsy or corneal buttons may reveal pockets of bacteria (usually Gram positive cocci) between intact lamellae of corneal stroma with a paucity of inflammatory infiltrate.

Treatment initially consists of cessation (or at least strict minimization) of topical steroids and prolonged use of topical bactericidal antibiotics. We recommend starting with vancomycin or other potent antibiotic with good gram-positive coverage and adapting medications depending on culture or biopsy results. Some authors suggest systemic antibiotics (including methicillin and penicillin) in severe cases. However, ICK is notoriously difficult to treat, demonstrating poor and slow response to medications. Debilitating stromal scars or recurrence of infection are common. In many cases, despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy, repeat penetrating keratoplasty or lamellar keratectomy may be required.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

SIGNSExam: needle-like crystalline pattern with a snowflake or ice crystal appearance of white opacities within the corneal stroma

Histopathology: biopsy or transplant specimen

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT

|

Fillmore PD, Graff JM, Goins KM, Infectious Crystalline Keratopathy (ICK): 72-year-old female with decreased vision. EyeRounds.org. February 12, 2007; Available from: http://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/cases/66-Infectious-Crystalline-Keratopathy-ICK.htm, 2007

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.