This patient was seen in the Comprehensive Ophthalmology Clinic at the University of Iowa. Her diagnostic workup prompted numerous systems-based questions regarding cost-effectiveness and coordination of care. Below are the details of the clinical exam, workup and the systems-based questions that arose along the way.

Chief Complaint: Floaters in both eyes (OU) for four months.

History of Present Illness: The patient is a 46-year-old female with no significant ocular history who was referred from an outside ophthalmologist for evaluation of persistent floaters in both eyes for four months. She denies seeing flashing lights in either eye. She has no history of trauma to either eye. She also denies decreased vision, eye pain, or eye redness.

Past Ocular History: No history of ocular surgery. She wears reading glasses.

Medical History: The patient has a history of bipolar disorder and gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Past Surgical History: Uterine cryotherapy for dysfunctional uterine bleeding, tubal ligation, lipoma resection from anterior abdomen, and surgical decompression of "trigger thumb"

Medications: Wellbutrin, Risperdal, Lamictal, Prevacid

Allergies: Sulfa-containing drugs cause pruritis.

Family History: The patient’s mother and grandmother have diabetes. Her grandmother also has "heart problems."

Social History: The patient is married and has three children. She denies alcohol use, but she has been smoking one pack of cigarettes every week for the last 6 months.

Review of Systems: Negative apart from the ocular symptoms noted above.

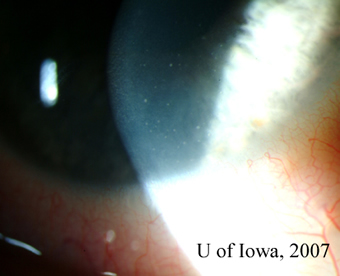

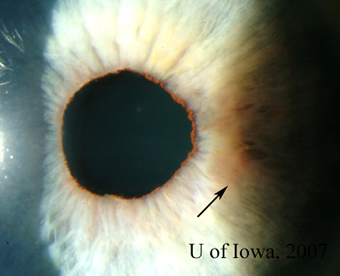

| 1A: Granulomatous keratic precipitates (KP) are seen in the inferonasal cornea of the right eye. | 1B: Iris nodule with surrounding dilated blood vessels and adjacent pupillary irregularity. |

|

|

The clinical perspective: The differential diagnosis at this point included both infectious and non-infectious causes of unilateral granulomatous uveitis with elevated intraocular pressure.

| Non-Infectious | Infectious |

|---|---|

|

|

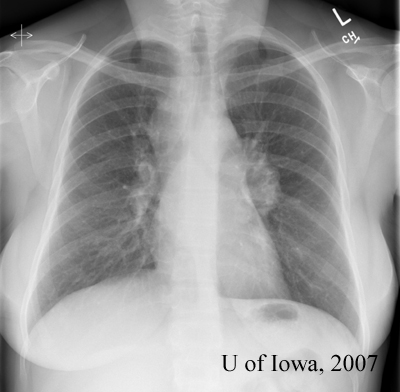

The goal was to rule out the more serious diseases first. Many of the other diagnoses (Fuchs’, glaucomatocyclitic crisis, for example) could be made primarily by exclusion. Therefore, the decision was made to order ANA (screen for autoimmune dysfunction), ACE (screen for sarcoid), RPR (screen for syphilis) and a chest Xray (screen for TB/sarcoid). We elected not to test for the HLA-B27 diseases (Reiter, Ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis) in part because they were lower on the differential and because the patient had no associated clinical findings.

The systems-based perspective: A cost-effective approach to workup includes refining a differential diagnosis and ordering only those tests that are necessary a final diagnosis. The costs of the tests that were ordered for our patient are as follows:

| ANA | $83.00 |

| ACO | $74.00 |

| RPR | $25.00 |

| Phlebotomy charge | $27.00 |

| Chest X-ray | $186.00 |

| Total | $395.00 |

We made the deliberate decision to perform a chest Xray and not a more costly chest CT in the hopes that the Xray would be able to provide screening information about the possibility of TB or sarcoid. Chest CT can, of course, be ordered if initial Xray results are equivocal. We eliminated unnecessary costs by not testing for Lyme disease and the HLA-B27-associated diseases for which there were no associated clinical findings.

The clinical perspective: The patient needs an ocular antihypertensive and a topical steroid to control her intraocular inflammation. We chose to prescribe Timolol for her IOP and Prednisolone 1% for the inflammation.

The systems-based perspective: It is important to ensure that patients have the means to pay for medications that they are prescribed. With so many different insurance plans and so many patients with no insurance at all, the cost of medication remains a formidable barrier to providing healthcare. In this case, the costs of the prescribed medications at UIHC for a patient with no insurance were as follows:

| Prednisolone 1% (5 ml bottle) | $16.09 |

| Timolol (5 ml bottle) | $14.35 |

| Total | $30.44 |

Our patient had a private insurance plan that covered a percentage of the cost of these medications. So here, prescribing affordable medications for our patient was easy. In more difficult situations, physicians can decrease costs to the patient and insurance company by prescribing generic medications instead of brand names, and by being judicious about the medications prescribed.

Prior to the patient’s follow-up visit, the results of the tests returned:

|

|

The clinical perspective: While the ocular, laboratory and radiographic findings are all suggestive of sarcoidosis, they are not diagnostic. The definitive diagnosis of sarcoidosis can be made by the combination of suggestive clinical findings combined with a tissue biopsy demonstrating non-caseating granulomas (Rothova, 2000). A conjunctival biopsy could therefore be helpful in establishing our patient’s diagnosis. The other option for this patient is to perform a transbronchial lung biopsy (given that she has bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy) – a procedure associated with increased medical risk.

Although the value of a non-directed conjunctival biopsy (i.e. a biopsy of conjunctiva that does not have granulomas) has been debated, at least two prospective studies demonstrate its utility in diagnosing sarcoid. A 1985 prospective study by Karcioglu, et al. (1985) of bilateral non-directed conjunctival biopsies in 28 patients showed that 28.5% of suspected sarcoid patients without conjunctival granulomas had positive conjunctival biopsies. A subsequent 1990 prospective study by Spaide, et al (1990) showed that among 47 patients with suspected sarcoidosis, 31.4% of patients without conjunctival follicles had positive biopsies. These two studies speak to the utility of performing bilateral non-directed biopsies in patients suspected of having sarcoid.

The systems-based perspective: As mentioned above, a tissue biopsy is essential for making a definitive diagnosis of sarcoidosis. In the case of our patient, tissue could be obtained by either a conjunctival biopsy or a transbronchial lung biopsy of her hilar lymph nodes. Not surprisingly, these two procedures come at different costs to the hospital. Below are the amounts billed at the University of Iowa:

| Conjunctival biopsy | Transbronchial lung biopsy | |

|---|---|---|

| Procedure charge | $910.00 | $1,717.00 |

| Procedure room charge | $572.00 | $1,485.00 |

| TOTAL charges | $1,482.00 | $3,202.00 |

The difference in total costs to the hospital between a transbronchial lung biopsy and a conjunctival biopsy is $1,720.00. Because the lung biopsy and the transbronchial biopsy can yield the same result (i.e. tissue diagnosis for sarcoid), there is a significant systems-based incentive to perform a conjunctival biopsy over a lung biopsy.

While the procedure charges are fixed, the ophthalmologist does have some control over the procedure room charges. The conjunctival biopsy "procedure room" refers to the minor procedure room where conjunctival biopsies and other procedures are often performed under local anesthesia. This cost may be decreased if not eliminated entirely if the ophthalmologist performs the conjunctival biopsy in the clinic room. This would increase the systems-based incentive to perform a conjunctival biopsy over a transbronchial lung biopsy.

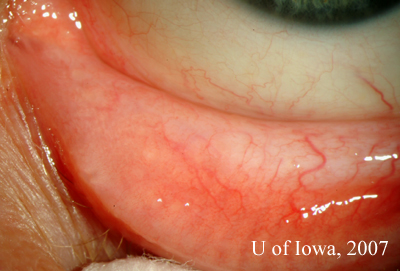

The decision was made to perform a conjunctival biopsy of the left eye. A 6 mm strip of inferior palpebral conjunctiva of the left eye was removed. The procedure was done in the minor procedure room under local anesthesia.

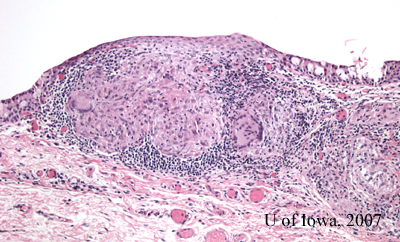

The pathology of the specimen revealed "non-caseating granulomas, consistent with the diagnosis of sarcoid." (Figure 4).

|

Diagnosis: We now have the appropriate clinical and histologic information to make the definitive diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis.

The clinical perspective: Sarcoid is a multisystem disease that can involve nearly every organ system. As such, good coordination and communication among healthcare providers is essential to ensure that the patient has optimal multi-disciplinary care.

In our case, we informed our patient’s primary care provider of her diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Together, we agreed to refer her to our rheumatology department at the University of Iowa for further management of her systemic disease. We agreed to allow the rheumatology providers to refer her to pulmonary specialist as they saw fit. We made an effort to establish all of her speciality care at the University of Iowa so as to facilitate coordination of care and communication among services.

Gandhi N, Oetting TA, Kirby P: Ocular Sardoidosis: A systems-based approach to diagnosis and treatment. EyeRounds.org. November 5, 2007; Available from: http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/76-Ocular-Sarcoidosis-Systems-Based.htm.

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.