Case Presentation: A female patient underwent a seemingly uncomplicated phacoemulsification cataract surgery with intraocular lens implant. On post operative day number one following surgery, the vision of this previously highly myopic female measured 20/200 without correction (improving to 20/40 with pinhole). Despite pre-operative goal to make the patient plano for distance vision, she now noted that her vision was better with her old glasses than without correction. Review of the chart made it clear to the operative team the wrong intraocular lens (IOL) had been surgically implanted; instead of receiving an 10.0 diopter IOL, the patient had received a 20.5 diopter lens.

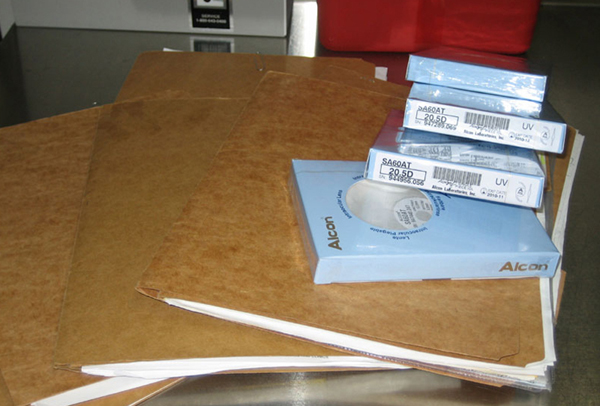

A review of the previous operative day with the nursing staff and the operating surgeons revealed that this patient had been confused with another female patient who underwent surgery the same day and received a 21.5 diopter IOL. Unfortunately, during the year when this took place, it was common procedure for all of the charts for the days' surgeries to be in the operating room (see Figure 1). The wrong female’s chart was used to select the IOL. This system error came in part because female patients are less common at the Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals. It was especially unusual for two female patients to be undergoing surgery on the same day. It was incorrectly assumed that the first female chart of the day was the correct patient. The operative surgeon did not personally double-check the chart and the patient’s name. As a result of this sentinel event, a very serious system flaw was recognized that had to be corrected.

|

The VA established a VA Root Cause Analysis (RCA) team that included members of the administration, nursing staff, and an outside surgeon. The team looked at all aspects of the system used to select an IOL and proposed several changes in the system of delivery of care that have eliminated similar events over the almost three years since this sentinel event. Number one is to only allow one chart in the operative room at any one time. Number two is to include a verification of the selection of IOL during the operative site "time out" procedure. The surgeon must have circled the pre-selected IOL on the printed calculation sheet and placed his or her initials verifying the selection. Number three is to specifically verify that the chart, IOL print out, signed consent, and patient ID band have the same name and identification number. Finally, when the selected IOL is opened for placement on the sterile field, the IOL power is read and verified to be the same power circled on the printout in the chart.

Discussion: Although rare, placement of the incorrect IOL in cataract surgery significantly affects visual outcome, patient satisfaction, trust in the care provider, and may expose the patient to significantly increased risk of further surgical complications if it is necessary to exchange the lens. If the incorrect lens is placed as a result of clinician error, the issue can easily become a target of litigation. Additionally, such an occurrence is classified as a Medical Adverse Event and is subject to mandatory reporting 1 in many states. This exposes the physician not only to litigation, but also to punitive fines and other forms of remediation up to and including permanent license revocation. As an example, Florida law 2 (456.072(1)(bb), F.S) now imposes a punishment that even on the first offense may include large fines, mandatory risk management classes, requirement that the physician give lectures on wrong-site surgeries, many hours of community service, and temporary suspension followed by probation. For any subsequent event, the punishment becomes harsher.

Placement of the wrong IOL can be included under the umbrella of ‘wrong-site, wrong-person, wrong-procedure’ surgical errors, which include any preventable error in patient, procedure, implant choice, or surgical site. For the sake of simplicity, these have been referred to as ‘surgical confusions’ by some authors. In ophthalmology, IOL-related errors are the most common of these. A 1999 review3 by Brick of 168 cases representing all cataract-related claims closed by the Ophthalmic Mutual Insurance Company (OMIC) over a ten-year period (33% of total claims closed) showed that IOL-related complications accounted for the largest number of cataract surgery claims, and of these, wrong IOL placement was the most common complication. This group also had the largest total indemnity, with an average settlement of around $28,000. Another study4 by Simon et al in 2007 looked at both the OMIC data and a New York State database of reported events and found 106 total ophthalmic surgical confusion cases over a 23-year period. The most common error was wrong IOL placement, comprising 63% of cases. Of these, 25% were due to incorrect preoperative measurements, and 69% were due to intraoperative errors including failure to check the lens specifications, no procedure for verification of the correct lens, confusion of patient name or wrong chart, nursing staff change during surgery, or damaged lens packaging. The average settlement for the OMIC cases in this study was around $36,000.

Prevention: In nearly all cases, placement of an incorrect IOL can be shown by root-cause analysis to have been a preventable error. A number of approaches to prevention have been published. Any strategy to minimize such errors begins with implementation of the Joint Commission’s Universal Protocol for Preventing Wrong Site, Wrong Person, Wrong Procedure Surgery, available online5. This consists of a pre-operative verification process, marking of the operative site, and a pre-procedural ‘time-out.’ The Veteran’s Health Administration took this one step further with its much more detailed and specific 2004 Directive Ensuring Correct Surgery and Invasive Procedures, available on the VA website6. However, even with 100% implementation of the Joint Commission Protocol and/or the VHA Directive, further steps are needed to avoid wrong IOL placement because of the specific preoperative and intraoperative problems encountered which are not addressed by these guidelines. The American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) has published a protocol specifically addressing IOL placement, with separate sections regarding both preoperative protocol for determining measurements and lens choice and intraoperative protocol to minimize opportunities for error in provision of the correct IO. Importantly, the AAO recommended protocol includes a specific ‘time-out’ just for the lens implant. The entire AAO document is freely available at the AAO website 7. The Academy’s suggested procedure for intraoperative IOL verification is as follows:

The AAO is clear to mention that these are only guidelines, and that each surgeon may be faced with unique and different situations requiring a tailored approach that works for their specific practice, as we have done in our VHA facility as described above. One group of experts was asked to discuss their own methods of ensuring correct IOL choice with several interesting approaches as discussed in an AAO article8. In Brick’s review 9of OMIC cases, he also outlines some more specific strategies for avoidance of lens-related errors, including training of technicians in keratometry and biometry, avoidance of outdated lens calculation formulas, maintaining a checklist of all the day’s IOLs in the operating suite to be rechecked just prior to lens insertion and regular use of only a few styles and models of IOL to avoid unnecessary confusion.

Prevention is obviously key to all of the approaches discussed here, but if an event occurs, another important but often overlooked aspect to dealing with surgical errors is communication with the patient after the event. OMIC’s Cataract Surgery Risk Management Recommendations10 says it nicely: "Surprisingly, in many instances, the patient never filed a lawsuit. Patients who are promptly told the truth, offered an apology, and granted a waiver of the fees associated with the procedure tend to be more forgiving."

Conclusion: Wrong IOL Implantation - a type of "Wrong site" surgery: In conclusion, implantation of the incorrect IOL is the most common preventable error in ophthalmic surgery. The problem may actually be much larger than is known based on the limited statistics available, especially given that the increasingly common mandate of harsh disciplinary action against surgeons. Unfortunately, there may be underreporting of such events. In an effort to combat this trend, some states - along with the Federal government - are now implementing anonymous, voluntary adverse event reporting systems. This type of error is nearly 100% preventable using a systems-based approach of preoperative and intraoperative standard practices. We have employed a root-cause analysis around one such event at our institution and implemented a modified strategy for ensuring correct surgery and maximum patient safety. We are confident that with successful implementation of our improved protocol, we will avoid any similar errors for many years to come.

Course: In our case, the patient had an uneventful IOL exchange. She was fully informed of the error and appropriately concerned but did not pursue litigation or disability

Suggested citation format: Roller B, Oetting TA. Blebitis: Intraocular Lens "Time Out": A Systems Based Case. EyeRounds.org. January 15, 2007; Available from: http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/72-IntraocularLensTimeOutSystemsBased.htm.

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.