Chief Complaint: 64-year-old male who first noted the onset of oscillopsia five months prior to presentation.

History of Present Illness: He had never noticed this in the past, and he noted that it worsened in up-gaze and in central gaze and improved in down gaze and in left and right lateral gaze.

PMH/FH/POH: His medical history was significant for hypercholesterolemia and an bicycle accident with multiple skull fractures 15 years prior to presentation. His medications included Simvastatin 80 mg qd and Aspirin 81 mg po qd.

|

|

|

|

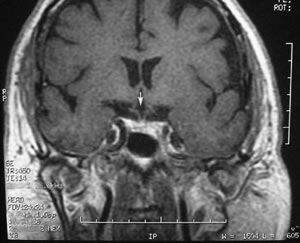

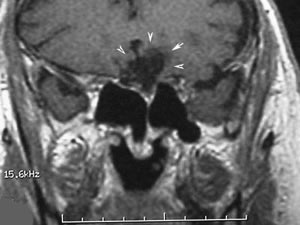

| Coronal, T1 MRI scan of the head showing split optic chiasm (See arrowhead). | MRI scan showing changes associated with prior head trauma which resulted in encephalomalacia. |

|

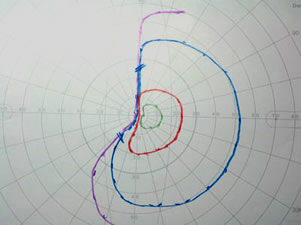

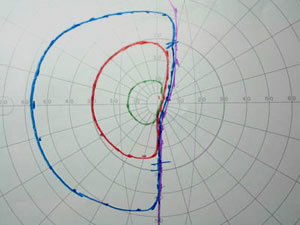

The first case reported of see-saw nystagmus was in 1913 by Maddox (1913). See-saw nystagmus (SSN) is a rare ocular presentation with less than 50 cases reported in the literature. SSN is characterized by the cyclic movement of the eyes with a conjugate torsional component and a disjunctive vertical component. In one half cycle, the eye will rise and intort and the other eye will fall and extort; then, in the next half cycle, the vertical and torsional components are reversed. The wave form can be either pendular or jerk, otherwise known as see-saw and hemi-seesaw nystagmus respectively.

There are many etiologies of SSN including: most commonly parasellar masses (Barton 1995), mesodiencephalic disease (Halmagyi et al., 1994; Halmagyi & Hoyt 1991), brainstem stroke (Halmagyi et al., 1994; Halmagyi & Hoyt 1991; Mastalglia 1974), head trauma, lack or loss of crossing fibers in the optic chiasm, multiple sclerosis (Samkoff & Smith 1994), arnold-chiari malformation, congenital (Rambold et al., 1998), whole brain irradiation, and intrathecal methotrexate (Epstein 2001). Most of the cases of SSN following trauma have been in the acute setting. There have been two cases reported of delayed SSN following trauma which resulted in immediate chiasmal lesion with bitemporal hemianopsia (Eggenberger 2002). It was thought that in these cases, the SSN was a delayed response to the traumatic brain injury. However, our case is unique in that the patient developed an interval change in his MRI imaging of a pontine stroke prior to the onset of the SSN.

It has been felt that SSN may be caused by more than one lesion that affects the visuovestibular system. Perhaps, the integration of the nervous system of eye movements occurs at many levels.

SSN likely represents oscillations involving central otolithic connections especially in the interstitial nucleus of Cajal (Halmagyi et al., 1994). It has also been thought to be related to an unstable visuovestibular control system (Nakada & Kwee 1986). The interstitial nucleus of Cajal (INC), adjacent to the medial longitudinal fasciculus in the midbrain tegmentum, has been frequently implicated in the pathogenesis of SSN. Fibers from the INC project to the oculomotor and trochlear nerves, vestibular nuclei and spinal cord. A disturbance in the INC itself or in its projections may contribute to the mechanism underlying SSN.

See-saw nystagmus requires an intact INC and vestibular connections (Rambold et al., 1998; Cochin et al., 1995; Suzuki et al., 1995). We believe that delayed SSN in our patient is the result of a double hit to the visual vestibular pathway as this patient had chiasmal injury in the past but had developed a stroke in the pons as evident on the MRI scan (Figure 3). SSN, in our patient, was not the result of traumatic chiasmal injury alone.

Treatment of SSN has been suggested with clonazepam (Cochin et al., 1995). Others have used gabapentin as GABA-nergic pathways are involved. Ethanol has also been used to decrease the SSN (Frisen & Wikkelso 1986). The patient was continued on his daily aspirin and was started on clonazepam 0.5 mg po bid. The patient's SSN improved on clonazepam, but the adequate dose had not yet been achieved and will require adjustment.

EPIDEMIOLOGYCauses include:

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT

|

Quisling S, Kardon RH. See-Saw Nystagmus: 64-year-old male who first noted the onset of oscillopsia five months prior to presentation. EyeRounds.org. February 21, 2005; Available from: http://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/case23.htm.

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.