The University of Iowa

Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences

Posted January 22, 2024

Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy (FECD) is a corneal dystrophy affecting primarily the deepest layer of the cornea, known as the corneal endothelium. It is the most common corneal dystrophy, affecting 4% of the American population over the age of 40, [1] and is the most common indication for corneal transplantation in the US. [2] As this condition is frequently encountered (especially in cornea clinic), it is a great topic for medical students to be familiar with prior to their ophthalmology rotations.

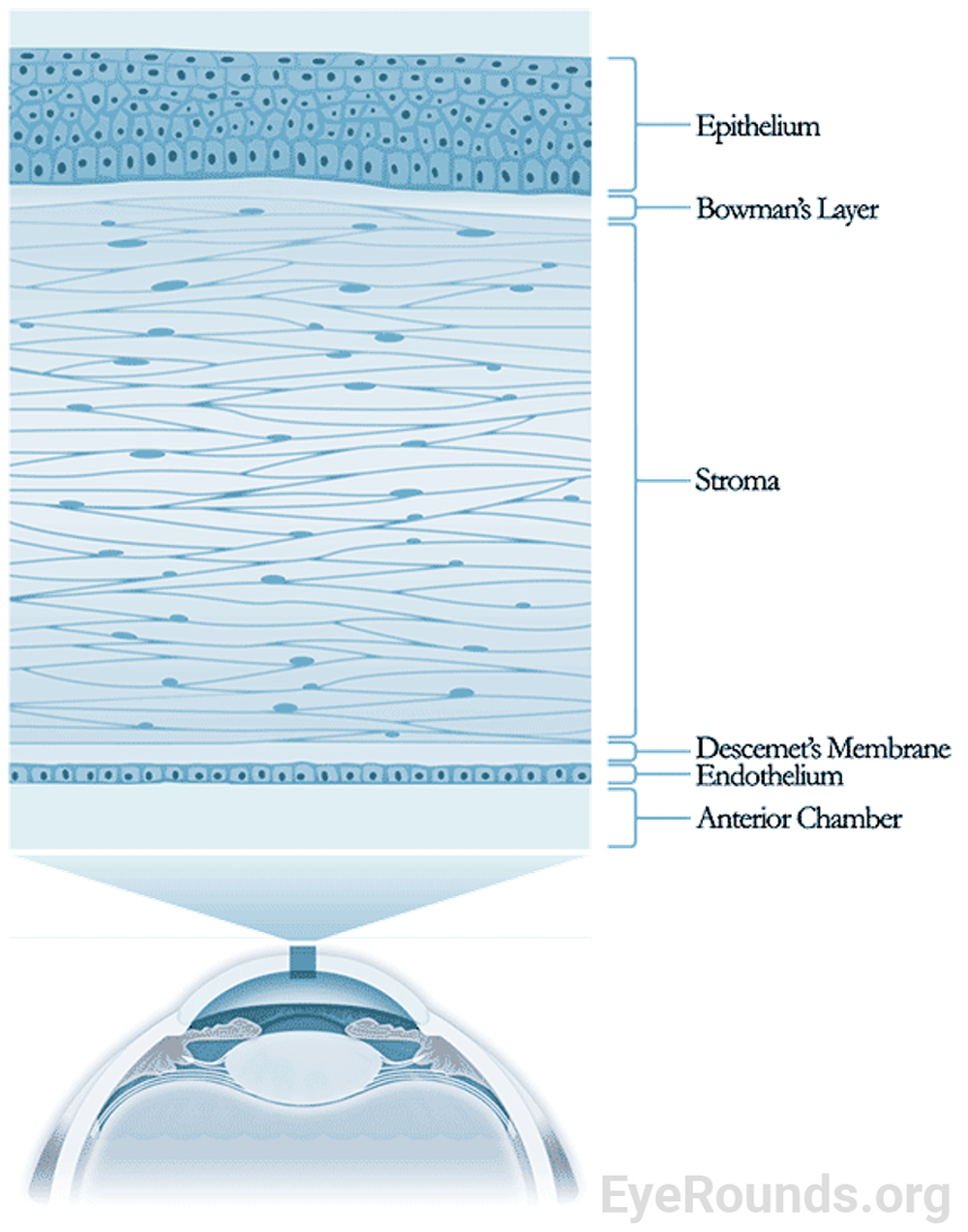

To understand how FECD affects vision, an understanding of corneal anatomy is essential. The cornea is the transparent “window” that allows light to enter the eye and reach the photoreceptors in the retina. The cornea, combined with the air-tear interface, produces approximately 70 percent of the eye’s refractive power.[3] The cornea is comprised of five layers, consisting of cellular and acellular components. From superficial to deep the layers are as follows (Figure 1):

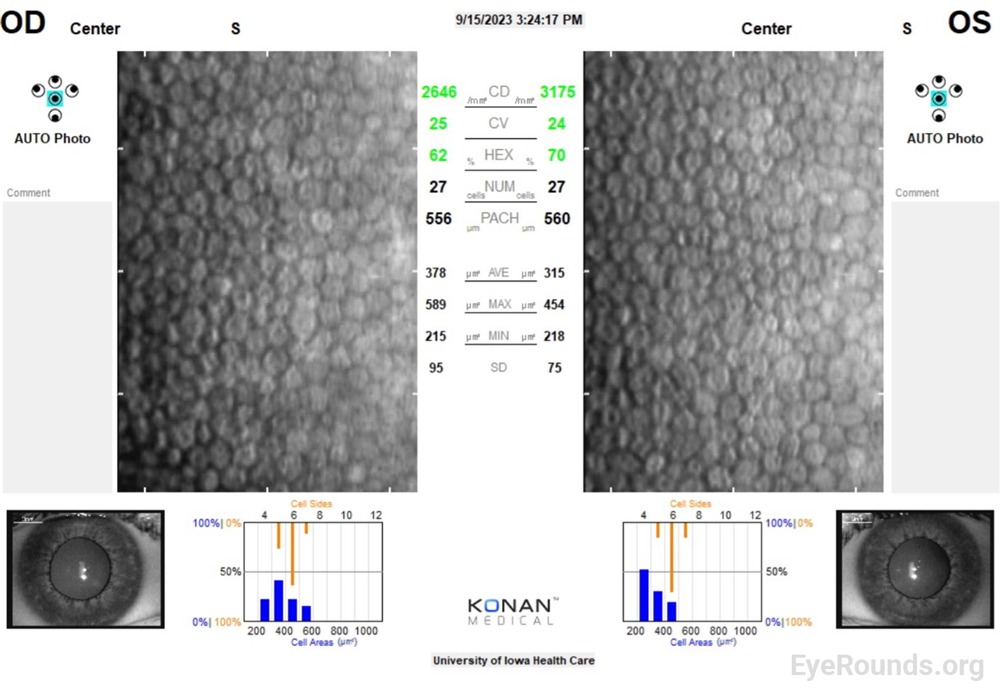

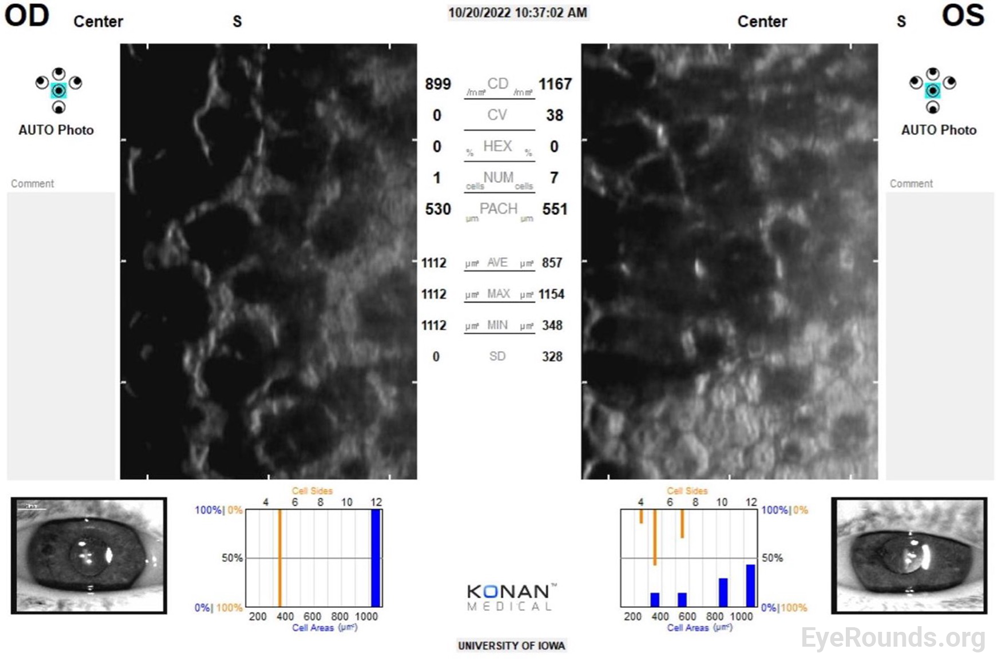

Though it is a normal part of aging, endothelial cell death is severely exacerbated in FECD.[2] Since corneal endothelial cells do not regenerate, neighboring cells must migrate and fill gaps in this cell layer.[3] This leads to a loss in barrier and pump function, and disrupted regulation of proper corneal hydration. As endothelial cells die, remaining cells migrate, grow, and lose their characteristic hexagonal shape in order to fill in these gaps. This behavior results in the characteristic polymegathism and pleomorphism, respectively, that is observed on specular microscopy in patients with FECD (Figure 3). Additionally, FECD is a disease characterized by abnormal extracellular matrix deposition, which leads to the buildup of collagen excrescences, known as guttae, that accumulate, initially centrally, on the endothelium and can be detected on slit lamp examination.[4] These degenerative changes become visually significant over time, particularly as poor pump function leads to stromal edema that decreases corneal transparency and scatters light.

The condition is polygenic, meaning there have been many genes identified that can cause FECD. Of these, the TCF4 intronic trinucleotide repeat expansion is the most common genotype, and typically leads to a later onset of disease (e.g., manifesting in the 6th and 7th decades of life).[2] The TCF4 gene encodes for transcription factor 4, a broadly expressed transcription factor that may play a role in nervous system development. Additionally, COL8A2, which encodes the alpha 2 chain of type VIII collagen, has been identified as a gene for early-onset FECD (e.g., 2nd decade of life).[3] The mechanism of cell-death is not yet fully known but involves increased vulnerability to oxidative stress. [4-7]

The Krachmer grading scale can be used to classify severity of FECD and track progression of the disease. Grading is based on the characterization of guttae on slit lamp examination.[8]

Once 4+ guttae is noted on exam, stromal edema, stromal haze, epithelial edema, and epithelial bullae (blisters on the epithelial surface resulting from endothelial pump dysfunction) will be tracked over time, as the presence of visually significant edema is an indication for surgical intervention.

Early symptoms of FECD may include blurry or hazy vision in the morning that improves throughout the day. This diurnal variation occurs because of stromal fluid accumulation overnight while the eyes are closed, limiting surface evaporation. As the disease progresses, blurriness improves less throughout the day, and patients may complain of glare in dim lights, halos, decreased contrast sensitivity, and possible pain from ruptured bullae or microcystic edema.[2,3]

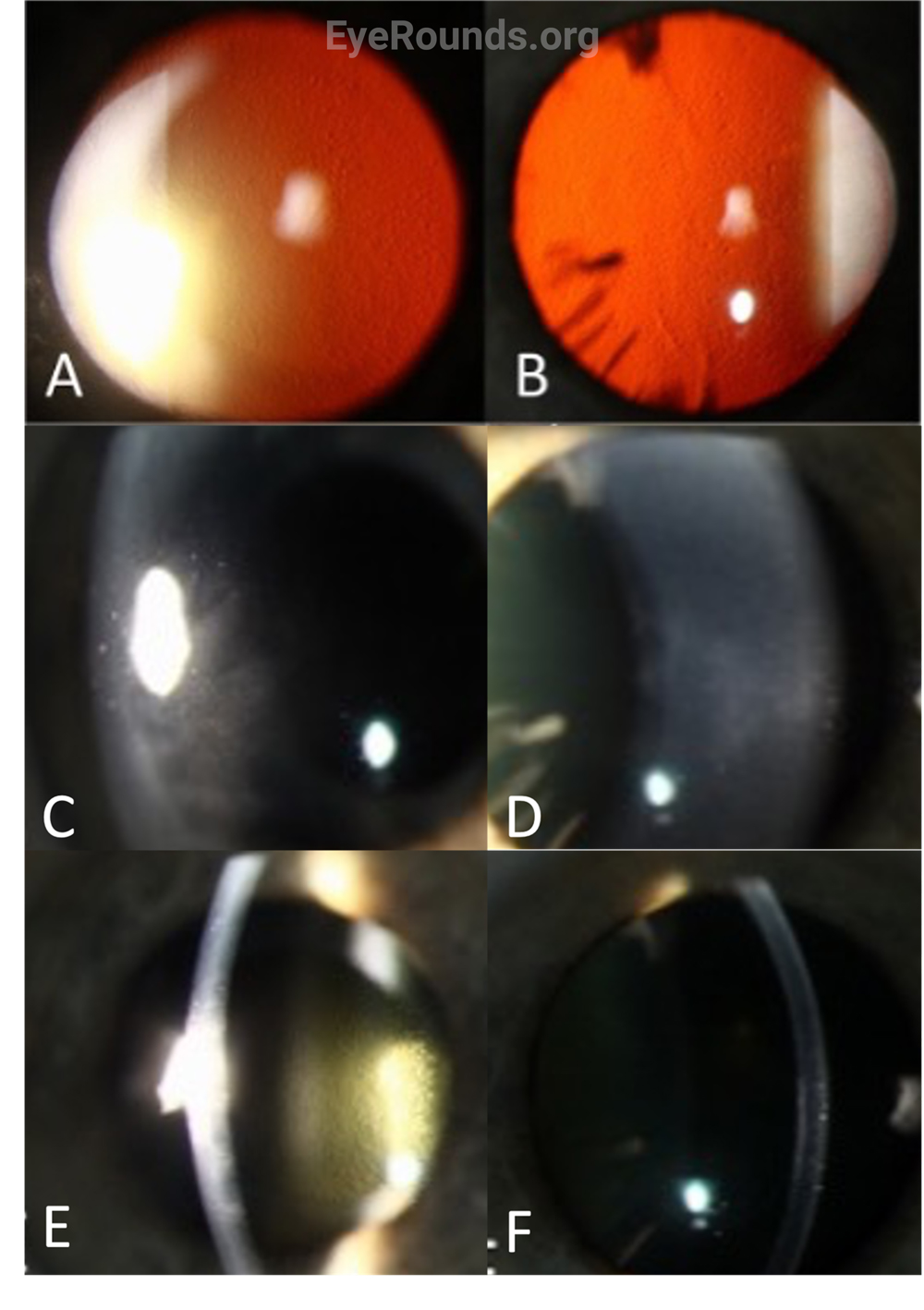

Early in the disease, the only finding may be guttae, which often start centrally and then spread peripherally (Figure 4 A,B,E,F). The easiest way to appreciate subtle guttae is either by indirect illumination or retroillumination on slit lamp exam. As the disease progresses, stromal edema becomes noticeable (Figure 4 C,D) and can be visualized by direct illumination with a narrow parallelepiped slit. As stromal edema worsens, bullous keratopathy can be noted on exam. For patients with extreme pain, surface staining of the cornea with fluorescein can highlight areas of ruptured bullae, which may indicate a need for antimicrobial coverage to allow for healing of these epithelial defects. In end-stage FECD, exam findings include subepithelial fibrosis, scarring, and peripheral superficial vascularization as a result of long-standing edema and cellular damage.[2]

Pachymeters utilize ultrasound energy in order to measure central corneal thickness. While FECD is a clinical diagnosis, pachymetry is both supportive in the diagnosis and useful for tracking disease progression, as the cornea will progressively thicken as more endothelial cells are lost and the stroma becomes more edematous.[3] For context, a normal, healthy cornea has a central corneal thickness of 545 micrometers.

Specular microscopy is an imaging tool for assessing endothelial cell density. While not necessary for the diagnosis, it can be supportive and can aid in tracking changes over time. Endothelial cell counts will decrease as FECD progresses (Figure 3).[3] For context, a normal healthy cornea in an adult has an endothelial cell density of approximately 2000-3000 cells/mm2. Additionally, specular microscopy allows visualization of the aforementioned polymegathism, pleomorphism, and loss of hexagonality changes that are characteristic of endothelial cells in FECD.

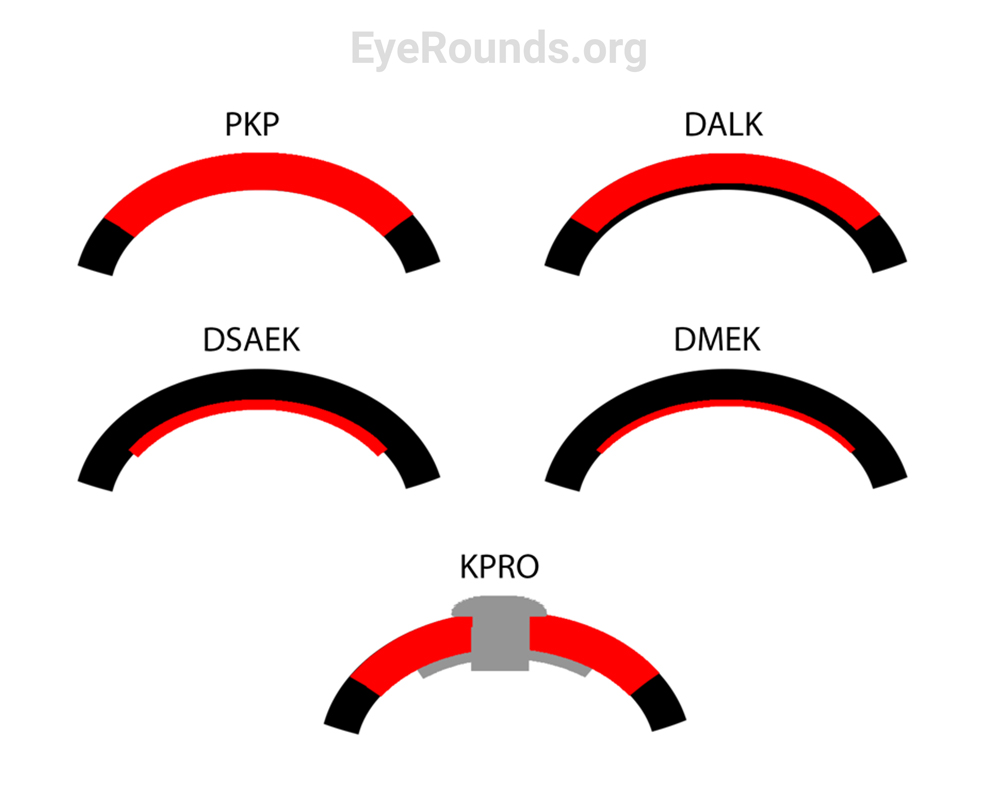

There are currently no definitive medical treatments available for FECD. However, patients can use hypertonic saline drops (i.e. Muro128) for symptomatic relief. This hypertonic solution creates a concentration gradient which draws fluid out from the anterior stroma, thereby alleviating early morning blurred vision and photophobia/pain caused by epithelial edema. Unfortunately, hypertonic saline drops are incapable of clearing a cornea with severe or posterior stromal edema. For this reason, surgery (partial thickness corneal transplantation, i.e. endothelial keratoplasty (EK) is the mainstay of treatment.[3] Historically, full thickness corneal transplantation, or penetrating keratoplasty (PK), was the only available surgical treatment for these patients. PK was reserved for patients with end-stage disease, characterized by severe corneal edema, scarring, bullous keratopathy, and neovascularization. However, since the development of EK techniques in the late 1990s and early 2000s, which are less invasive and have lower rates of complications, PK is no longer used as the initial surgical management for FECD. Currently, patients with FECD are offered EK when they have developed visually significant corneal edema but do not have significant, permanent stromal scarring that would compromise visual outcomes of the surgery.

Keratoplasty, or corneal transplantation, involves replacing damaged portions of the patient’s cornea with functional graft tissue from a deceased donor (i.e. allogeneic transplantation). The corneal endothelium is the damaged component in patients with FECD. Therefore, transplantation in these patients involve partial thickness grafts of the endothelium, known as endothelial keratoplasty (EK) (Figure 5). Examples of endothelial keratoplasty include:

Both EK techniques require the use of a gas bubble into the anterior chamber to help position the graft against host tissue. EK, particularly DMEK, has a faster rate of vision recovery, better quality of vision, and a lower rejection rate than DSAEK. For this reason, DMEK is the preferred technique for corneal transplantation in the absence of complex anatomy (e.g., prior glaucoma surgery or prior retinal surgery).[6] DMEK surgical video available at EyeRounds.org (https://eyerounds.org/atlas-video/DMEK.htm). While visual outcomes post-transplant are typically quite good, there is always a risk of graft detachment, failure, or rejection, even years down the road. Some patients may require multiple transplants in their lifetime, and most will require prophylactic corticosteroid drops (i.e. prednisolone acetate 1%) for the rest of their life to prevent rejection.[7] Discussion on the identification and management of graft rejection and failure is beyond the scope of this article.

Shonka S, Dotson AD, Greiner MA. Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy: From One Medical Student to Another. EyeRounds.org. January 22, 2024; Available from https://EyeRounds.org/tutorials/fuchs-endothelial-corneal-dystrophy-med-student/index.htm