Chief Complaint: Vision changes in the left eye

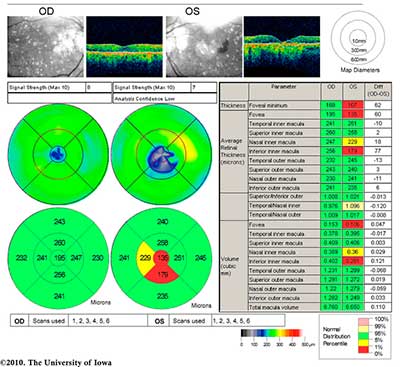

History of Present Illness: A 76-year-old established female patient presented to the clinic with an increase in a central scotoma in her left eye that was discovered with home Amsler grid testing. She had a 17 year history of atrophic age-related macular degeneration (AMD) with retinal changes greater in the left than in the right eye. She denied flashes, floaters, pain, or photophobia. Her most recent eye appointment was two months prior, at which time her visual acuity measured 20/25 with correction OD and 20/160 with correction OS.

Past Medical History: Atrophic AMD, hypercholesterolemia, hypothyroidism, colon cancer treated surgically and now in remission for 20 years with no recurrence. No history of ocular surgeries or previous eye trauma.

Family History: Mother had glaucoma

Social History: Non-smoker

Medications: Atorvastatin, levothyroxine, beta carotene, calcium carbonate, latanoprost in both eyes (OU) at bedtime.

Ocular examination:

|

The patient, having known atrophic AMD in both eyes, was diagnosed with progression to neovascular AMD in the left eye. She was treated with monthly bevacizumab (Avastin®) injections in the left eye (OS) with visual acuity improvement back to her baseline of 20/80 OS. Figure 3 shows her fundus photos after treatment with Avastin OS.

|

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is an ocular disease affecting 35% of individuals over the age of 75 [1]. It is the leading cause of irreversible blindness in elderly people in the United States. Both forms of AMD, atrophic (dry) and neovascular (wet), are thought to be initially caused by oxidative stress to retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells. Atrophic macular degeneration is more common (85%) than neovascular macular degeneration, with progression from dry to wet in approximately 10% of individuals diagnosed with dry AMD. AMD is a complex disorder likely caused by multiple genetic variations as well as environmental factors, and several mechanisms have been proposed to explain its pathophysiology.

The etiology of drusen deposition in AMD may involve activation of the complement cascade (for a histopathologic analysis of AMD, please see this tutorial page). AMD has been linked to certain genetic variations in the compliment factor H gene (HF1/CRH), which normally produces a complement control protein (HF1) that is responsible for inactivating C3b and thus inhibiting activation of the alternative compliment pathway. It is thought that in some people with these specific, at-risk variations, HF1 has decreased affinity for C3b, leading to increased activation of the alternative complement cascade, especially following inflammatory stimuli or oxidative stress. This leads to complement deposition and accumulation in the form of drusen beneath the retinal pigment epithelium. Interestingly, these at-risk haplotypes were most strongly associated with exudative or neovascular AMD [2,3].

Another theory involves the activity of γ-secretase (Figure 4). This enzyme plays a crucial role in the production of amyloid-β, another component of drusen in dry AMD. The enzyme is also thought to damage the protective effects of pigment epithelium derived factor (PEDF), a neurotrophic agent produced in RPE cells. PEDF is a known antagonist of VEGF. Overproduction of γ-secretase may both increase drusen formation and reduce the effect of PEDF, thereby allowing unregulated VEGF activity and progression to wet AMD [4].

A third proposed mechanism involves the effects of bone morphogenic protein 4 (BMP4), a protein responsible for senescence and apoptosis in many different cells in the body (Figure 5). This protein is differentially expressed in atrophic compared to neovascular AMD. BMP4 expression is increased in atrophic AMD and leads to oxidative stress induced RPE senescence. However, in neovascular AMD, BMP4 expression is decreased in the RPE (possibly due to pro-inflammatory mediators), leading to decreased apoptosis and increase in VEGF and thereby allowing for progression of angiogenesis and development of neovascular AMD. Thus, the conversion between atrophic to neovascular AMD is thought to be due to changes in the microenvironment as RPE cells undergo senescence [5].

Dry AMD:

(Also referred to as atrophic AMD or non-exudative AMD)

The Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group (AREDS) in 2001 demonstrated the effectiveness of high doses of vitamin C and E, beta carotene, zinc, and copper in delaying progression of dry AMD (Figure 6) [6]. One fourth of AMD patients in the study were given all of the vitamins and minerals studied (500 mg vitamin C, 400 IU of vitamin E, 15 mg beta carotene, 80 mg zinc oxide, and 2 mg copper), a quarter were given zinc oxide, a quarter were given antioxidants, and a quarter were given placebo (Figure 6). After following the patients for seven years, the study demonstrated that AMD patients who took both antioxidants and zinc supplements had a 25% risk reduction in developing advanced AMD. The patients who benefited most from these supplements were category 3 and 4 AMD patients, quantified by extensive intermediate drusen, large drusen, non-central geographic atrophy, or visual acuity <20/32 in at least one eye (see this helpful page for more information on staging AMD). There was no significant effect on the development of cataract [6].

The AREDS2 study began 2006 and was completed in 2012 with the purpose of investigating whether addition of omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (DHA + EPA), carotenoids (lutein and zeaxanthin), or a combination of both to the original AREDS combination would further reduce the progression of acute macular degeneration [7]. Additionally, the study group aimed to investigate the effects of reducing the zinc dose and eliminating the beta carotene completely from the original AREDS formulation. They conducted a randomized, double-blinded study involving 4203 individuals between the ages of 50 to 85 who were at risk for advanced AMD. Groups were randomly assigned to receive EPA (650 mg) + DHA (350 mg), zeaxanthin (2 mg) + lutein (10 mg), EPA + DHA and lutein and zeaxanthin, or placebo. Participants were randomized to either take the original AREDS combination or another formulation variant of the AREDS combination. AREDS variants included lowered zinc doses, a combination without beta carotene, or both. After following patients for six years, primary analyses of the study demonstrated that adding EPA + DHA, zeaxanthin + lutein, or both did not lead to further risk reduction or progression to an advanced state of AMD [7]. However, among patients taking the beta carotene formulation, there was an increased incidence of lung cancer in former smokers [8]. As a result, modern formulations avoid inclusion of beta carotene.

Wet AMD:

(Also referred to as neovascular AMD or exudative AMD)

There are three medications which form the mainstay of treatment for wet AMD: bevacizumab (Avastin®) [off label], Ranabizumab (Lucentis®), and aflibercept (Eylea®). Avastin is a 149 kDa full-body antibody to VEGF while Lucentis is a 48 kDa antibody fragment to VEGF that was designed to have higher affinity and theoretically more penetration [9]. Aflibercept is a 115 kDa soluble fusion protein consisting of an IgG backbone attached to extracellular VEGF receptor sequences of the human VEGFR1 and VEGFR2. As a decoy receptor, it binds VEGF-A more strongly than its natural receptors. Due to its high affinity to VEGF-A, it prevents the binding and activation of endogenous VEGF receptors, subsequently leading to a decrease in VEGF activity and decreasing angiogenesis and vascular permeability [10].

A trial of monthly injections over three months is an accepted schedule for the initial treatment of neovascular AMD. If the patient has responded, the same injection is used following either an as needed protocol (fixed follow-up intervals with review of OCT findings at each respective visit) or a “treat-and-extend” protocol whereby patients receive an intravitreal injection at each visit, with subsequent follow-up determined by their clinical and OCT findings, with adjunctive fluorescein angiography as indicated. Bevacizumab [off label] and ranibizumab (FDA approved in June of 2006) are humanized monoclonal antibodies that block vascular endothelial growth factor, thereby inhibiting angiogenesis. Both drugs are also thought to decrease vascular permeability [11]. The Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatment Trials (CATT) compared the efficacy of ranibizumab and bevacizumab at treat-and-extend vs fixed schedules over a period of one year. Visual acuity was followed to determine efficacy, and at one year the bevacizumab and ranibizumab group, as well as the monthly vs PRN group, produced statistically similar results at both schedules [12].

The CATT-2 trial was a continuation of the initial CATT study whereby patients who were initially assigned monthly injections in the first year of the CATT study were randomly reassigned to either PRN or fixed treatment schedules. Bevacizumab and ranibizumab were again found to have equivalent efficacies. However, in the CATT-2 trial, PRN treatment dosing (started at one year or after initiation of treatment) resulted in decreased improvement of visual acuity when compared to treat-and-extend dosing. Notably, the improvements made during the first year in the treatment group receiving monthly dosing were not preserved when switching this same group to as-needed treatment in the second year [13].

The Inhibition of VEGF in Age-related choroidal Neovascularization (IVAN) was another randomized control trial seeking to compare bevacizumab and ranibizumab, as well as monthly vs. PRN schedules. This study demonstrated an increased risk of developing geographic atrophy among patients receiving monthly treatments as opposed to those on the treat-and-extend regimen [14].

The Canadian Treat-and-Extend Analysis Trial With Ranibizumab (CANTREAT) compared monthly ranibizumab with the treat-and-extend approach over twelve months. This trial compared visual acuity between the two groups and found that the treat-and-extend approach was non-inferior to monthly fixed schedule injections and achieved statistically similar results with significantly few injections [15]. The findings of CATT, IVAN, and CANTREAT have led many specialists to adopt bevacizumab as a first-line medication, with the treat-and-extend or as-needed protocols utilized over monthly injections.

Aflibercept (Eylea®) was FDA approved in 2011 for the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration following two clinical trials demonstrating its efficacy (VIEW 1 and VIEW 2). A two-year clinical trial comparing Eylea® (aflibercept), Avastin® (bevacizumab), and Lucentis® (ranibizumab) found that patients receiving Eylea had greater improvement in vision compared to those receiving Avastin if their vision was 20/50 or worse. Improvement was similar between patients receiving Avastin and Lucentis during the two-year study. This was contrary to initial results produced after following patients for one year which showed Eylea to have greater advantage. Improvements were similar between all three drugs if patients had visual acuities of 20/32 or 20/40 vision at the beginning of treatment [16].

Epidemiology

|

Signs

|

Symptoms

|

TreatmentDry AMD

Wet AMD

|

Swathi S, Benson C, Weingeist TA. Age-related Macular Degeneration: Progression from Atrophic to Proliferative. EyeRounds.org. Updated May 3, 2022; Original Aug 24, 2010; Available from: http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/118-AMD-progression.htm.

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.