"My eyes are red and they itch."

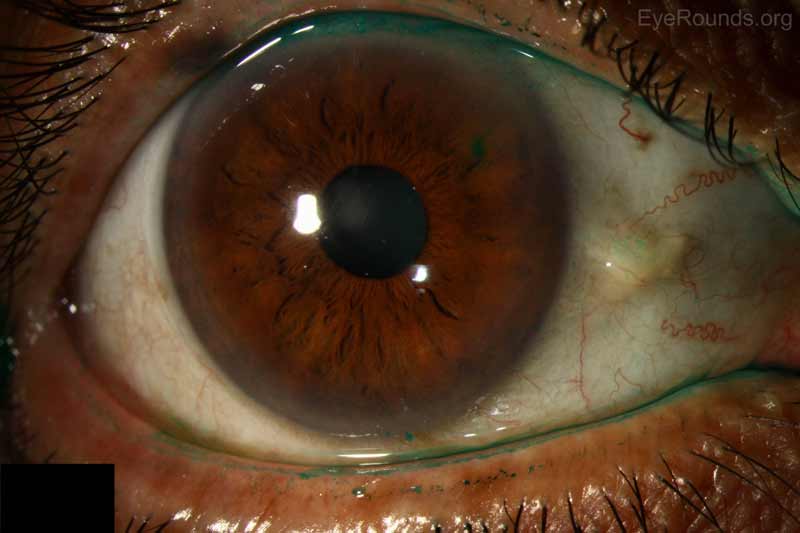

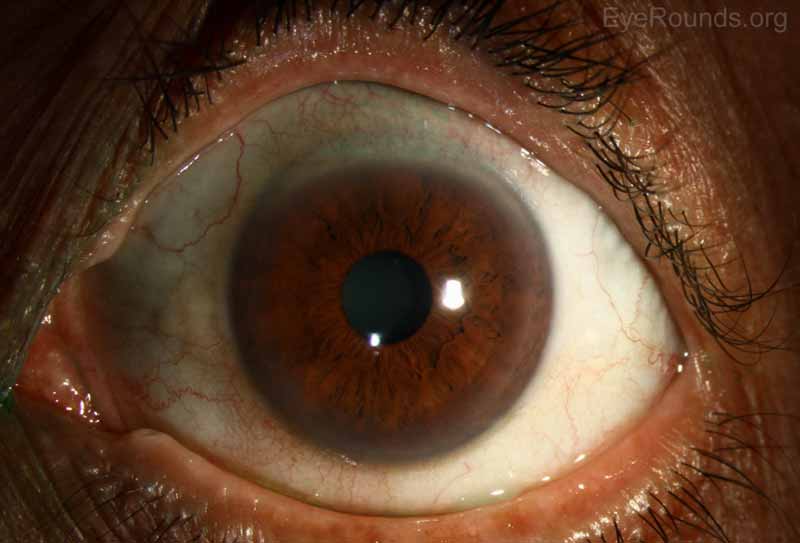

A 63-year-old male presents for evaluation of irritation and injection of both eyes, that is refractory to management with lubrication. He complains that both of his eyes are red and itchy. He denies any light sensitivity and reports that his vision is good. He has previously tried prednisolone and epinastine HCl in both eyes without significant improvement, in addition to regular use of artificial tears and a nighttime lubricating ointment.

|

|

|

|

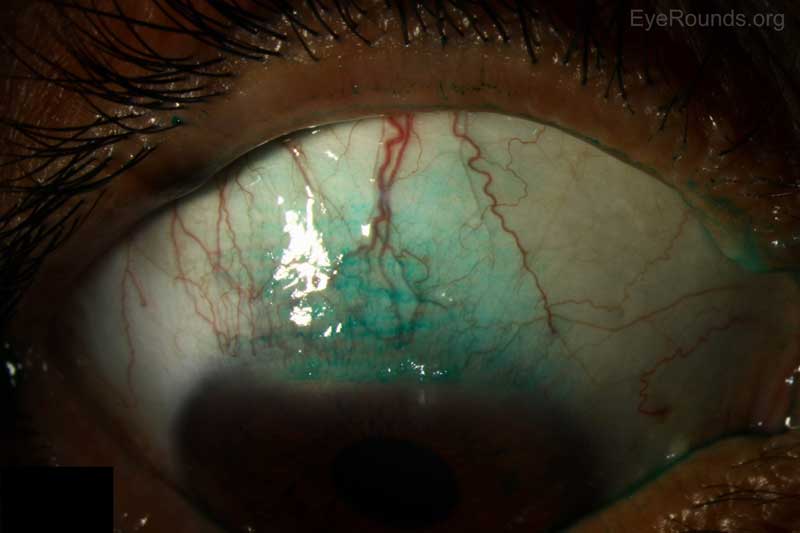

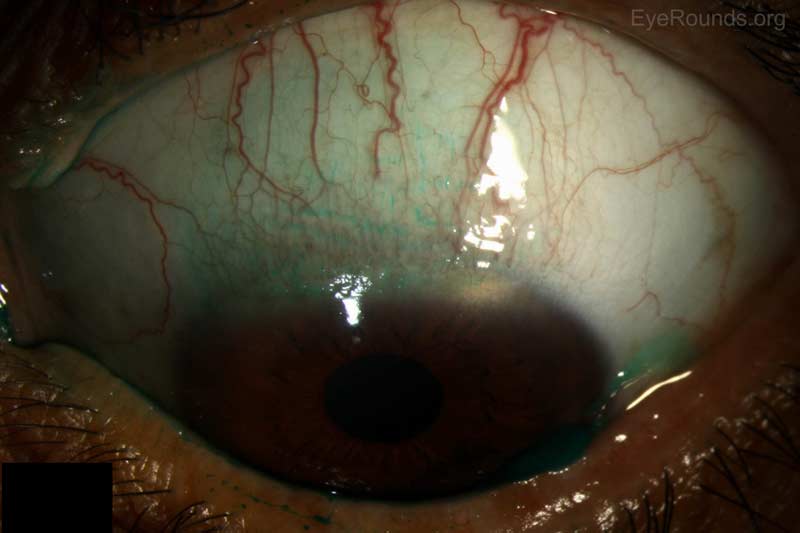

Figure 1: Anterior slit lamp photos of both eyes showing symmetrically devitalized epithelium in a superior sector of the conjunctiva, which stained positively with lissamine green.

The diagnosis of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis was suspected; therefore, the following laboratory studies were performed:

Thyroid function tests

Anti-CCP – Negative

Anti-Ro - Negative

Anti-La - Negative

Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis

Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis was likely first noted by Braley and Alexander in 1953 when they described a series of patients with superficial punctate keratitis and filaments [1]. In 1961 Thygeson further described the condition in a series of 12 patients with filamentary keratitis limited to the superior cornea with inflammation of the superior bulbar conjunctiva [2]. However, it was not until 1963 that Dr. Frederick H. Theodore gave a complete description of the disease and suggested its current name [3].

Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis, as described by Theodore, is characterized by:

Clinically, patients have thickened and hyperemic bulbar conjunctiva extending in a 10 mm arc from the superior limbus to the superior rectus while the inferior palpebral conjunctiva remains remarkably normal [1]. There can also be a papillary reaction of the superior palpebral conjunctiva and redundant bulbar conjunctiva. The superior one-third of the cornea is often involved with fine punctate staining. Rarely patients will develop corneal hypesthesia, with-the-rule astigmatism, or markedly decreased tear secretion. The natural history of the disease is characterized by a chronic course with gradual clearing. There are often short remissions early in the course of the disease. Patients with SLK are typically women (F:M=3:1) between 20 to 60 years of age who present with complaints of gritty foreign body sensation, burning, redness, irritation, or mucoid discharge in both eyes, although asymmetric involvement is not unusual [1,2,3]. The discomfort can vary in severity depending on the clinical signs. Decreased Schirmer's test has been seen in up to 24% of patients. An association with thyroid dysfunction and keratoconjunctivitis sicca has also been identified in 30% and 25% of patients, respectively [3].

The etiology is not well understood with several potential causes having been proposed thus far. An autoimmune etiology has been deemed unlikely despite the associated thyroid abnormality because few inflammatory changes are seen on light microscopy, direct or indirect immunofluorescence [4]. It is not thought to be infectious and viral cultures have been universally negative with no viral particles seen on electron microscopy. In 1972, Wright postulated that the superior palpebral conjunctiva is responsible for initiating the pathological process as upper lid chronic inflammation can disturb the normal maturation of cells of the bulbar conjunctiva [1,5]. The disturbance of maturation in turn gives rise to symptoms and signs seen in SLK clinically. Critics have argued that the palpebral conjunctival inflammation is mild and it is difficult to determine whether the inflammation first begins on the bulbar or palpebral conjunctiva. Ostler initially proposed a mechanical mechanism in which abnormal movement of the upper eyelid leads to microtrauma between the superior palpebral and redundant bulbar conjunctival surface during repetitive blinking in susceptible individuals [1]. In 2000 Ivan Cher argued that the mechanical pathogenesis in SLK is likely multifactorial due to the following reasons: (1) lack of response to standard anti-inflammatory therapies, (2) stress and noxious factors of a myriad pathogenic sources acting on the tissue layers of the ocular surface causing repetitive microtrauma [6]. Researchers have recently identified increased amounts of mast cells, matrix metalloproteinases, and other cytokines in patients with SLK, and others have pointed to a decrease in local mucin production as an etiology [12,13]. There are numerous treatments directed at controlling inflammation, mechanical trauma and improving tear production. Unfortunately, no single treatment is uniformly successful, which points to a multi-factorial origin for SLK.

There is no gold standard treatment for SLK due to its multifactorial pathogenesis. Treatment is usually initiated with artificial tears and lubricating ophthalmic ointments.

Conservative topical treatment includes: topical steroids, vitamin A, cromolyn sodium, iodoxamide tromethamine, cyclosporine, ketotifen, rebamipide, and silver nitrate. Each of these treatments have been used with varying degrees of success, either by targeting inflammation or altering the relationship between the bulbar and palpebral conjunctiva. Chemocautery with silver nitrate has classically been used as a treatment and usually results in symptom relief for 4-6 weeks at which time retreatment is necessary.

For patients who are refractory to conservative therapies, conjunctival resection of the redundant conjunctiva is considered a highly effective technique to prevent microtrauma from regular blinking. Resection with amniotic membrane graft (AMG) was once thought to be superior due to its potential to combat conjunctival redundancy and prolonged inflammation [7]. However, Gris et al. found via their retrospective and comparative study that not only is conjunctival resection with AMG more expensive, it does not yield better outcomes compared to simple conjunctival resection and may even increase the recurrence risk [8]. An alternative surgical treatment is liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, which is also effective in malignant and premalignant ocular surface tumor treatment. Patients who were treated with cryotherapy all achieved long-term cures although repeat sessions were sometimes necessary [9].

Superior punctual occlusion has also been found to be curative as it targets the tear insufficiency aspect of SLK. Cautery and sutures are incorporated in order to occlude the lacrimal puncta in patients to prevent drainage. As a result, improved local tear accumulation leads to improved outcomes [10].

At UIHC, application of autologous serum eye drops (ASEDS) has been effective in healing conjunctival defects. It is also considered one of the main treatment modalities for severe dry eye and provides vitamin A, EGF, TGF beta, insulin-like growth factors and substance P, all of which are present in human tears and necessary for maturation and differentiation of cells [11]. Autologous serum eye drops can also act as an alternative or an adjunct to lacrimal punctal occlusion as both regimens aim to increase tear supply in the eye.

Additionally, botulinum toxin injection, orbital decompression and eyelid surgery has been used effectively, particularly in patients with Graves disease.

Epidemiology

|

Signs/Symptoms

|

Labs/Testing

|

Treatment

|

>Hu Z, Terveen DC, Beebe JD, Goins KM. Superior Limbic Keratitis. EyeRounds.org. October 28, 2016; Available from: https://eyerounds.org/cases/245-superior-limbic-keratitis.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.