Bilateral eye irritation, redness, and light sensitivity

A 70-year-old man with history of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, status post allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) at age 58, was referred from an outside ophthalmologist for chronic dry eye, eye redness, blurry vision, and photophobia with associated bilateral symblepharon.

He first started noticing eye irritation and redness eight years prior to presentation. From that time, he had a waxing and waning course of eye symptoms for which he was seen by multiple providers. Per outside records, his exams showed relapsing-remitting meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), diffuse injection, stromal haze, punctate epithelial erosions (PEE), lid telangiectasia, and symblepharon. He had been treated with multiple courses of topical steroids, which up until recently, had led to some improvement of his ocular symptoms. At the time of referral, he was using prednisolone four times daily in both eyes.

Of note, seven months after his HSCT while tapering from oral prednisone, the patient had a flare of systemic acute graft versus host disease (GVHD) with a widespread blistering cutaneous rash, oral mucosal sores, and dry, red eyes. He was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone.

Ocular:

Systemic:

The patient was retired from a career of factory work. He has three adult children. He smoked one half pack of cigarettes per day (PPD) since age 25, which he recently reduced to a quarter PPD. He denied use of alcohol or recreational drugs.

Aside from what is detailed in the history of present illness, the patient also complained of oral pain secondary to dental caries and buccal mucosal ulceration.

Full extraocular movements OU

Full OU

Normal on both sides

|

|

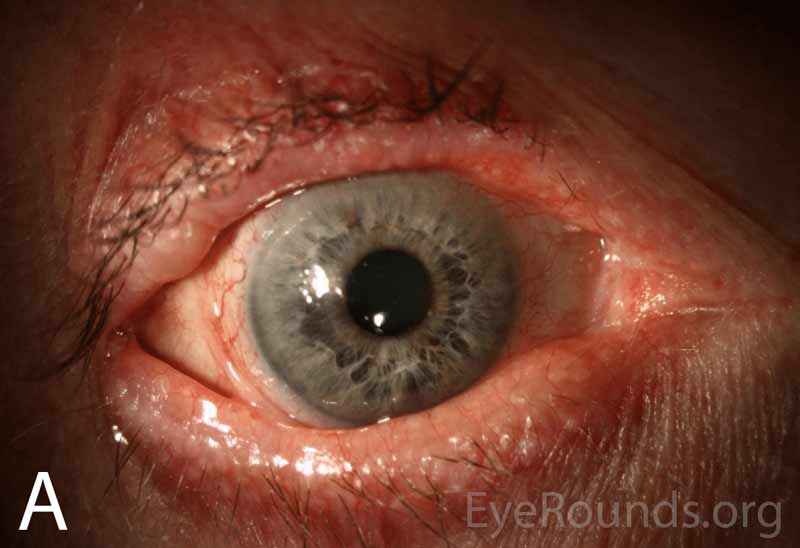

Figure 1A-B. Wide-field slit lamp photographs of the right and left eyes at initial presentation. Note the irregularity and thickening of the eyelid margins, eyelid telangiectasias, punctal fibrosis, MGD, diffuse injection, bulbar conjunctival banding temporally consistent with symblepharon, and keratinization of the plica and caruncle nasally. There is superior corneal pannus in the right eye (A).

|

|

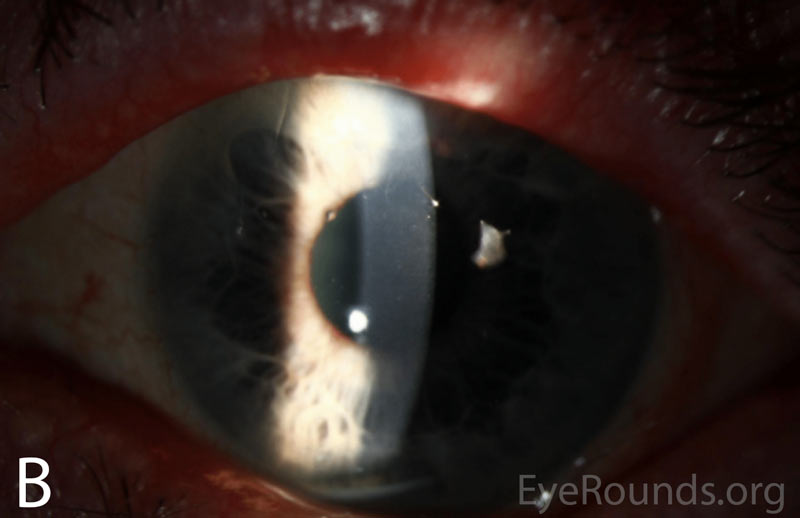

Figure 2A-B. Slit lamp photographs of the right and left eyes at initial presentation. In both eyes, note diffuse epithelial haze and scattered punctate epithelial erosions.

Normal disc, macula, vessels, and periphery, OU.

Prior to his referral to the University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics (UIHC) Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, the patient had dry eye, redness, photophobia, and decreased visual acuity that followed a waxing and waning course over a period of eight years. He was repeatedly treated with oral doxycycline, topical steroids, and aggressive lubrication, which seemed to improve his symptoms and vision marginally. He was ultimately referred to UIHC for worsening bilateral symblephara despite topical steroid treatment, which raised concern for ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP).

On initial presentation at UIHC, his exam was thought to be most consistent with chronic GVHD or OCP, based on the presence of bilateral symblephara, buccal mucosal ulcerations, and dental caries. At that time, he was continued on topical prednisolone acetate 1% drops three times daily OU, as well as aggressive lubrication with preservative-free artificial tears every two hours and nightly lubricating gel. He began using autologous serum eye drops (ASEDs) the following month.

Upon follow up, his symptoms and exam were minimally improved on the above regimen. Conjunctival biopsies were obtained and showed "epithelial changes and scarring most consistent with chronic GVHD." Immunofluorescent studies did not support a diagnosis of ocular cicatricial pemphigoid.

Given the biopsy results, a diagnosis of chronic GVHD was thought most likely. His prednisolone acetate 1% was increased to four times daily and ASEDs were continued every two hours in both eyes. Over the next two months his surface remained stable, with occasional blurred vision and recurrent trichiasis. He was continued on this regimen with regular follow up every three months to monitor disease progression, intraocular pressure, secondary cataract progression, and consideration of adjunctive topical cyclosporine.

Chronic graft vs. host disease

Chronic GVHD is a systemic disease that can occur any time after an allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplant is performed. The hallmark of chronic GVHD is widespread fibrosis, collagen deposition, and auto-antibody production that commonly affects the skin, lungs, and mucus membranes, which can include the ocular surface and associated secretory glands [1]. This disease entity can be contrasted with acute GVHD, which is an illness that more commonly occurs in the immediate post-transplant period. The diagnostic criteria for chronic GVHD were established in 2005 by a National Institute of Health Consensus Conference and most recently revised in 2014 [2].

Chronic GVHD is a major complication of allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, with 37% of patients developing the disease within the first year [3] and a cumulative incidence of 64% [4]. Ocular involvement is common, with a large retrospective study finding 33.3% of patients receiving HSCT develop ocular disease although values up to 60-90% have also been reported [5-7]. Notable risk factors for the development of chronic GVHD include prior acute GVHD, peripheral blood stem cell transplants (PBSCT), female donor to male recipient transplant, and EBV-seropositive donor [5]. The disease was once defined as occurring greater than 100 days after transplant, but now it is recognized that chronic GVHD can occur at any time after HSCT [2].

Chronic GVHD can be compared with acute GVHD, a severe inflammatory illness that presents early in the post-transplant period, often while the patient is still hospitalized [8]. Acute GVHD is slightly less common than chronic GVHD, with a reported cumulative incidence of 20% [4]. The acute form of the disease less commonly involves the eye, with a reported incidence of 1.33% in a recent retrospective study [5]. Additionally, the presence of ocular involvement in acute GVHD is a poor prognostic factor, with a mortality rate of approximately 90% [8].

Both forms of ocular GVHD are driven by T-cell-mediated inflammatory damage. However, the pathways by which T-cells incite inflammation in the two forms are thought to be different. The exact mechanism of chronic GVHD is poorly understood but the hallmark of the disease is increased IFN-g production [9], which causes a presentation similar to other autoimmune conditions [10]. There is a notable loss of central immune tolerance, resulting in self-reactive T- and B-cells in the periphery [11]. As donor stem cells interact with host T-cells, it is proposed that type 2 T-helper cells produce increased levels of cytokines including TGF-b, although this has only been demonstrated in animal models [12]. This cytokine production results in a reduction in regulatory T-cells and an increase in type 17 T-helper cells, causing widespread T-cell-mediated damage, auto-antibody production, and tissue fibrosis [13, 14]. Inflammatory injury from chronic GVHD commonly affects the skin, lungs, and mucus membranes, but can affect any organ system in the body [15].

Chronic ocular GVHD most commonly presents as keratoconjunctivitis sicca secondary to destruction of the conjunctiva, loss of goblet cells, fibrosis of the lacrimal glands, and meibomian duct fibrosis [16]. These fibrotic changes occur as pro-inflammatory mediators and type 2 T-helper cells result in mononuclear infiltrates, epithelial destruction, and fibrogenesis at these sites [17]. Patients develop severe dry eyes with increased ocular surface inflammation, impaired tear production, and rapid tear evaporation. The impairment of the ocular surface by inflammation can further lead to complications such as limbal stem cell deficiency, corneal scarring, symblepharon, entropion, and trichiasis [8, 18].

Disease mechanisms are better characterized in acute GVHD, a disease in which recipient antigens are attacked directly by donor T-lymphocytes [19]. The organs most commonly affected are skin, causing desquamation and bulla formation; liver, causing cholestatic disease and hyperbilirubinemia; and bowel epithelium, causing severe diarrhea [2]. Given the skin manifestations, patients may present similarly to those with toxic epidermal necrolysis [20].

The defining feature of chronic ocular GVHD is one of severe dry eye with conjunctival inflammation; symptoms occur on a spectrum. The most commonly reported symptoms are bilateral eye irritation, pain, burning sensation, photophobia, redness, blurred vision, and/or foreign body sensation [16].

Common exam findings include MGD, rapid tear break up time, decreased tear production, punctate epitheliopathy, conjunctival hyperemia, and corneal haze. As the disease progresses and surface inflammation increases, there can be development of corneal filaments, corneal scarring, cicatricial entropion, trichiasis, and/or symblepharon [21-23]. The exam may also reveal periadnexal dermatitis and vitiligo [23]. Late complications can include cataract, uveitis, retinal microvasculopathy with cotton-wool spots, vitreous hemorrhage, and/or optic disc edema [24].

Although the eyes are not widely considered a target organ for acute GVHD, when it does occur the hallmark of acute ocular GVHD is a pseudomembranous conjunctivitis with epithelial sloughing. Though, the most common ocular symptoms are also those of dry eye. These patients are often critically ill with other systemic complications [8].

Diagnosis of ocular GVHD is made clinically based upon degree of clinical suspicion in patients with keratoconjunctivitis and a history of allogenic HSCT. The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research published a review on ocular GVHD which included recommended evaluation measures for dry eye severity [25]:

Dry eye symptoms can be graded from 0 - 3 using the NIH Organ Scoring system, which is a standardized and validated tool that grades chronic GVHD severity by organ system [2, 27].

Although not required for the diagnosis of ocular GVHD, a conjunctival biopsy can show findings that are supportive of chronic GVHD. These changes include epithelial keratinization, a decrease in goblet cells, vacuolar alteration of basal cells, epithelial atrophy, and scarring from chronic disease [28]. A biopsy can also be useful when the diagnosis is not clear, or when there is concern for other pathologies such as OCP.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) released an updated consensus statement on the management of chronic GVHD in 2015 with systems-focused recommendations of disease management, of which the complete guidelines are beyond the scope of this review [15]. They identified four supportive care goals for chronic ocular GVHD: lubrication, control of tear evaporation, control of tear drainage, and decreasing surface inflammation [15].

Increased lubrication can be achieved through the judicious use of preservative-free artificial tears and nightly lubricating gels or ointments [29]. Although the NIH report lists oral muscarinic agonists such as cevimeline and pilocarpine as potential treatments due to their use in other dry eye syndromes [30, 31], there is little evidence of their efficacy in GVHD. Tear evaporation can be improved in the setting of MGD with warm compresses [32] and oral doxycycline [33], as well as through the use of moisture chamber goggles or scleral lenses [15, 34]. Tear drainage can be reduced through the use of temporary or permanent punctal occlusion [35].

There are a variety of ways to decrease surface inflammation, with limited evidence available to support the efficacy of specific therapies. The current first-line treatment is topical steroids, which non-specifically decrease ocular surface inflammation [36]. One retrospective study found that topical prednisolone acetate 1% drops produced a complete resolution of symptoms with a mean therapy duration of seven weeks [36]. Concerns with topical steroid use include the potential for development of cataracts, steroid-induced ocular hypertension, and increased risk of infectious keratitis [37]. Topical cyclosporine-A 0.05% has also been shown to decrease inflammation with significantly fewer side effects than steroids by inhibiting T-cell activation and downregulating inflammatory cytokine levels in the conjunctiva, although it appears to be less efficacious [38]. The NIH report recommended higher doses, such as cyclosporine 0.1%, to decrease surface inflammation [15]. There is also strong evidence that ASEDs used every two hours can produce a notable decrease in surface inflammation by a number of mechanisms including supplying platelet derived growth factor [39] resulting in improved visual acuity, improvement in symptoms, and decreased need for artificial tears [40]. If topical or local therapies are no longer effective, the patient's hematologist/oncologist should be consulted for consideration of systemic immunosuppressive therapy [41].

Acute GVHD is less likely to be encountered by the ophthalmologist, as it often occurs in the immediate post-transplant period in a severely ill patient [8]. The treatment depends on the specific organ systems involved, but the mainstay of treatment of severe systemic disease including in cases of ocular involvement is T-lymphocyte suppression. Most commonly, this will be performed with methylprednisolone and adjustment of the patient's current immunosuppressive therapy [42].

EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

MANAGEMENT

|

Goldstein AS, Wilson CW, Greiner MA. Chronic Ocular Graft Versus Host Disease. EyeRounds.org. Posted August 8, 2019; Available from https://EyeRounds.org/cases/287-GVHD.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.