Chief Complaint: New photopsias and temporal visual field loss in the left eye (OS)

History of Present Illness: A 74-year-old man was referred by an outside clinic for evaluation of suspected retinal detachment versus choroidal effusion OS. A week prior, he presented with episcleritis for which he was started on topical prednisolone drops. Shortly after starting the drops, he noticed photopsias and a crescent-moon shape in the temporal visual field of his left eye.

There was no history of autoimmune or inflammatory disease. He denied joint pain, fatigue, fever, skin rashes, or cough. He had no prior history of ocular inflammation, trauma, or surgery except for uncomplicated cataract extraction in both eyes (OU) two months prior.

Past Ocular History: Pseudophakia OU

Medical History:

Medications:

Allergies: No known allergies

Family History: Non-contributory

Social History: Non-contributory

Review of Systems: Unremarkable except for what is detailed in the history of present illness

OCULAR EXAMINATION

Differential Diagnosis:

Idiopathic

Inflammatory

Neoplastic

CLINICAL COURSE

Given the recent episode of episcleritis, an inflammatory process was suspected. However, an infectious and inflammatory work-up including rheumatoid factor (RF), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), lysozyme levels, syphilis antibody, and QuantiFERON-TB Gold were unremarkable. Given that his symptoms worsened after using topical steroid for episcleritis, bullous central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR) was considered. However, fluorescein angiography did not show findings consistent with CSCR, and OCT did not demonstrate significant choroidal thickening.

The patient was started on topical atropine and oral prednisone 40mg, dose limited by his history of diabetes. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) disease was considered but eventually ruled out given that choroidal effusions are unusual for this disease and that there was a lack of significant improvement in subretinal fluid (SRF) after 11 days of treatment with oral prednisone. Given the relatively short axial eye length (AEL) of 20 mm and absence of any inflammatory or autoimmune findings, the presentation was most consistent with uveal effusion syndrome (UES).

The patient underwent scleral window surgery in the left eye. Intraoperatively, the sclera was noted to be thick. Pathology from the excised scleral flaps showed no underlying abnormality of the sclera. Given that the AEL was not in the nanophthalmic range, the patient was diagnosed with type 2 idiopathic UES.

After surgery, the choroidal effusions slowly decreased, and the exudative retinal detachment resolved. Five months after surgery, visual acuity had improved to 20/40-2 cc. However, the patient was still visually symptomatic, and residual subfoveal subretinal fluid and shallow choroidal effusions remained. Diffuse “leopard-spot” pigmentation was observed throughout the posterior pole OS as the subretinal fluid resolved. The effusions continued to slowly improve and were nearly resolved at last follow-up eight months following surgery with visual acuity improved to 20/20. The “leopard-spot” appearance of the fundus persisted.

DIAGNOSIS: Idiopathic uveal effusion syndrome, type 2.

DISCUSSION

Etiology/Epidemiology

Uveal effusion syndrome (UES) is a rare condition that presents with serous choroidal effusions, often associated with serous retinal detachments and shifting subretinal fluid. This condition was first described in 1963 by Schepens and Brockhurst [1]. Later, studies suggested that this disorder was associated with nanophthalmos and scleral abnormalities that lead to either compression of vortex veins by thick sclera or increased resistance to transscleral outflow of intraocular protein [2,3]. Notably, the term UES is used when other causes of uveal effusion (often associated with hypotony or inflammation), such as trauma, scleritis, pars planitis, surgery-induced serous effusions, choroidal inflammation, uveal neoplasms, or lymphoid hyperplasia, have been excluded [4].

A UK-based study reported the annual incidence of UES to be 1.2 per 10 million population [5]. It is reported to be seen most frequently in middle-aged, hyperopic men. No specific risk factors for the condition have been described.

Broadly, UES can be divided into “nanophthalmic” and “idiopathic,” which occurs in normal sized eyes with variable scleral thickness [5]. Based on clinical features and histopathology, Uyama et al. divided patients with UES into three types [6]:

Pathophysiology

There are several hypotheses about the pathophysiology of UES related to impairment in the mechanisms that remove protein and fluid extravasated from the choroidal circulation [4]. In the human eye, unlike other tissues, the suprachoroidal space is not drained by lymphatics, and proteins escaping from the choriocapillaris are removed by diffusion across the sclera. Impairment in this mechanism can lead to the accumulation of protein in the suprachoroidal space, causing osmotic fluid retention.

The most widely accepted theory is that in patients with UES, there is a primary scleral abnormality in which the sclera has an altered structure and permeability that may be secondary to deposition of glycosaminoglycan (GAG)-like material in the interfibrillary spaces of the scleral collagen fibers [7]. Impaired trans-scleral outflow of albumin because of these changes is thought to create a high osmotic pressure in the choroid that retains fluid. Additionally, thickened sclera may also cause compression of the vortex veins, hampering venous outflow and resulting in congestion of the choriocapillaris [4]. Together, impaired osmotic forces secondary to reduced trans-scleral protein diffusion and impaired hydrostatic forces secondary to vortex vein compression lead to UES, with the relative contribution of each of the two mechanisms varying from one individual to another. However, not all eyes with UES have been shown to have scleral abnormalities on histological examination.

Symptoms/Signs

Patients with UES can present with loss of vision, metamorphopsia, and visual field abnormalities. Inferior serous retinal detachment and choroidal effusions may lead to a superior scotoma, and a gradual loss of the superior visual field is the most common complaint in the initial stages. A lack of pain and significant inflammation is helpful to differentiate UES from scleritis. IOP is usually normal in UES, and other causes should be considered if the pressure is low [8].

The defining feature of UES on examination is the presence of choroidal effusions that may expand to involve most of the peripheral choroid. Associated serous retinal detachment with shifting subretinal fluid may also occur, and visual loss is mainly caused by a detachment involving the fovea.

Chronic subretinal fluid leading to secondary changes in the retinal pigment epithelium are seen as “leopard-spot” changes, which may lead to permanent visual loss if the fovea is involved [5]. High magnification biomicroscopy and OCT can be used to differentiate this from retinitis pigmentosa in which the pigment is intraretinal.

Patients who have UES secondary to nanophthalmos may have associated high hyperopia and/or a history of angle closure glaucoma.

Diagnosis/Work-up/Imaging

Since UES is a diagnosis of exclusion, an inflammatory and autoimmune workup should be done to rule out other conditions that can cause uveal effusions.

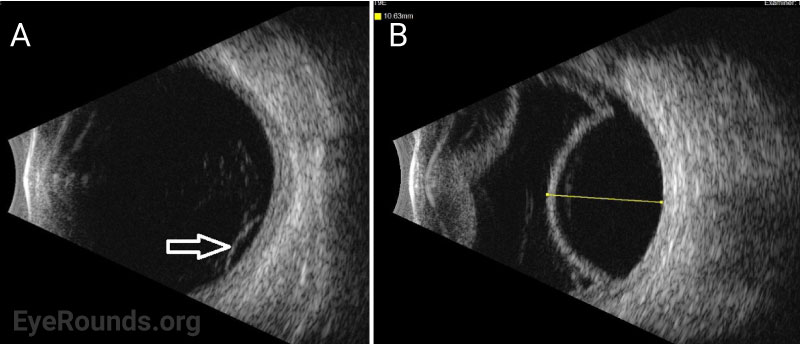

Ocular ultrasonography can reveal choroidal and/or retinal detachments as well as annular thickening of the choroid (seen best with ultrasound biomicroscopy) and is helpful to rule out other causes of choroidal effusions such as choroidal tumors or posterior scleritis. Axial eye length measurement by standardized A-scan ultrasound can identify nanophthalmos. Ultrasound biomicroscopy can be helpful in measuring scleral thickness. A value of greater than 2 mm is abnormal [9].

OCT can demonstrate increased choroidal thickness, engorged choroidal veins (seen as large areas of hyporeflectivity) or areas of expansion of the suprachoroidal space. Indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) can confirm the presence of dilated choroidal vessels.

Fluorescein angiography (FA) is helpful to rule out other causes of exudative retinal detachment such as bullous CSCR. Later, when leopard-spot hyperpigmentation develops, FA may show areas of hypofluorescence corresponding to those spots without evidence of leakage. Acutely, the leopard spots are hyperfluorescent on fundus autofluorescence (FAF) but can eventually show a mix of hyper- and hypofluorescence [10].

Scleral specimens obtained during surgery should be sent for pathology to look for abnormalities in collagen arrangement and deposition of GAGs between the collagen fibers.

Treatment/Management/Guidelines

The disease follows a relapsing-remitting course. If the effusions are small and peripheral, they may be observed. However, subretinal fluid that involves or may potentially involve the fovea is an indication for intervention. Medical management is often attempted prior to surgical intervention, though the results are variable in the literature. However, one study describing 104 eyes with UES but without nanophthalmos or scleral abnormalities (type 3) showed that steroid therapy (oral, topical, or periocular) led to resolution of effusions in 95% of patients within 3 months [11].

For many patients, surgery is the treatment of choice when medical management is ineffective. The goals of intervention include allowing drainage of the subretinal fluid and reducing scleral resistance to allow fluid to escape from the suprachoroidal space. Various techniques targeting the sclera have been developed and include scleral decompression near the vortex veins, partial thickness sclerotomies without decompression, punch sclerotomy, or full-thickness sclerotomy under a partial thickness scleral flap. The most common surgical technique is to create full-thickness sclerotomies based on the method described by Gass in 1983 [12]. These are made in each quadrant creating fistulae between the suprachoroidal and the subtenon’s space to allow drainage of the fluid. Ozongul in 2017 described a staged approach to treatment where the first step was creation of partial thickness sclerotomies in all or some quadrants, followed by repeat surgery if there was failure of resolution or a recurrence. Further steps included application of mitomycin C to reduce fibrosis and maintain patency of the fistula, followed by punch sclerostomy with subretinal fluid drainage or vortex vein decompression [13].

The prognosis after surgical treatment is variable in different studies. Johnson and Gass described resolution of effusions in 83% of cases after partial thickness sclerotomies, with an average time of 2.4 months for retinal reattachment. Despite surgery, recurrence is common, and was reported to occur in almost a quarter of eyes in that study [14].

In conclusion, UES is a rare condition for which a variety of treatment strategies exist, however there are no consensus guidelines for management.

DEFINITION AND ETIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

|

RELATED ATLAS ENTRY: Uveal Effusion Syndrome

Ahmad NUS, Goldstein AS, Binkley EM. Idiopathic Uveal Effusion Syndrome. EyeRounds.org. Posted April 25, 2023; Available from https://EyeRounds.org/cases/339-idiopathic-uveal-effusion-syndrome.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.