Chief Complaint: 22-year-old male presented to the clinic 2 days after a single vehicle motor vehicle accident who complained of decreased vision in the right eye (OD).

History of Present Illness: Patient fell asleep while driving his truck and had no recollection of the crash. He was not wearing a seat belt. His truck had apparently rolled several times. His airbag reportedly had deployed. He was taken to the local emergency treatment center (ETC). There he was noted to have several back contusions, a laceration on the left elbow, and a bruise on his forehead. Computerized tomography (CT) of the head was negative for fracture or intra-cranial bleed. Approximately 1 hour after leaving the ETC, he noticed vision loss OD.

Ocular History: No previous ocular disease history. No eye surgery, no previous eye nor head trauma.

Medical History: No other health issues. Symptoms as noted in History of Present Illness—review of systems was otherwise negative.

Medications: None

Family History: Noncontributory

Social History: Noncontributory

EXAM OCULAR

|

|

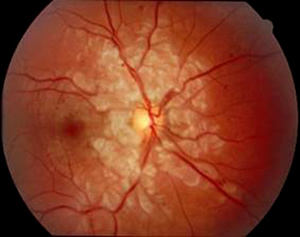

| 1A: Superficial retinal ischemia/cotton wool spots are seen in the distribution of the radial peripapillary capillary distribution. A few small hemorrhages are also visable. Note the relative sparing of the optic nerve and peri-venous areas. | 1B: Normal fundus, OS |

Given the patient's history and retinal findings, he was diagnosed with Purtscher's Retinopathy, OD.

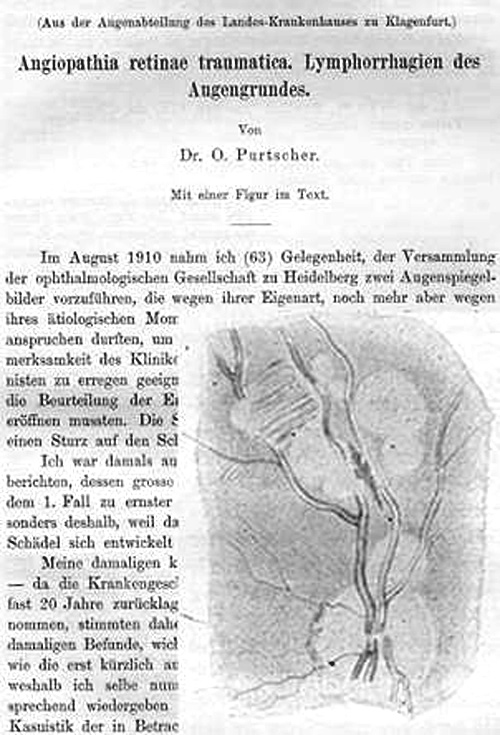

Angiopathia retinae traumatica was first described by Dr. O. Purtscher in 1910. The retinopathy that now bears his name was discovered in two severely traumatized patients with head injuries (Purtscher 1912). Dr. Purtscher noted glistening white spots and superficial retinal hemorrhages in these patients. Papillitis was also evident. Two years later, he reported three more cases associated with head injury. He proposed a mechanism of lymph stasis secondary to increased cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) pressures and named the condition angiopathia retinae traumatica.

|

Since that time, the clinical picture first described by Purtscher has been associated with:

Patients with Purtscher's (or Purtscher's-like) retinopathy may notice severe vision loss either immediately or up to 48 hours after the event. Vision may decrease to 20/200 or worse and may be unilateral or bilateral. The prognosis for recovery is variable, with roughly 50% of patients complaining of persisting blurred central vision. There is no proven treatment for Purtscher's retinopathy. Though there are anecdotal reports of drug therapies, including megadose corticosteroids (Atabay et al., 1993), improvement in these situations may be related to controlling some type of underlying systemic vasculitis, which has been loosely associated with some cases of Purtscher's retinopathy. Most often, the clinician will simply monitor the patient for visual recovery and ascertain that other injuries are addressed.

Though the exact pathophysiology of Purtscher's retinopathy is not known with certainty, there are three main proposed mechanisms. The classic mechanism proposes that head injury or chest compression generates an intravascular hydrostatic "shock wave" that is transmitted to the retinal vasculature resulting in endothelial damage. This can affect retinal veins, macular capillaries, and radial peripapillary capillaries resulting in the clinical picture seen. However, this does not explain non-traumatic cases of Purtscher's or cases with unilateral involvement. Second, it is proposed that emboli of fat, air, or amniotic fluid can cause the clinical appearance of Purtscher's. In addition, there is a complement mediated hypothesis. Complement C5a is known to be associated with trauma, acute pancreatitis, and systemic vasculitic diseases, and has been proposed to play a role in the development of Purtscher's. By this theory, component C5a initiates leukocyte aggregation and embolization. Leukoembolism in concert with other factors initiates intravascular coagulation of platelets.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

OCULAR SIGNSRetina

Optic Nerve

Fluoroscein Angiography:

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT

|

Suggested citation format: Maassen J, Oetting T. Purtscher's Retinopathy: 22-year-old male with vision loss after trauma. EyeRounds.org. May 18, 2005; Available from: http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/39-PurtschersRetinopathyAngiopathiaRetinaTraumatica.htm.

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.