Chief Complaint: Decreased visual acuity and foreign body sensation in the right eye for the past months.

History of Present Illness: The patient is a 67-year-old male who presents with a pigmented conjunctival lesion in his right upper eyelid. He initially noticed it 1 year ago, but was asymptomatic until 6 months ago when he started experiencing decreased visual acuity and a foreign body sensation in that eye. He initially thought that his symptoms were due to dry eye.

Past Ocular History: He wears glasses, but has no other ocular history.

Medical History: He has multiple chronic medical conditions including hypertension, coronary artery disease, hypercholesterolemia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, migraines, degenerative joint disease and bilateral hearing aids.

Medications: Fosinopril, omeprazole, baby aspirin, and sertraline

Allergies: Beta blockers and atorvastatin

Family History: He has a cousin with cutaneous melanoma

Social History: Non-smoker

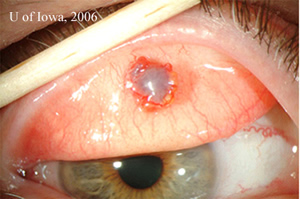

| 1A: External examination reveals a mass within the right upper eyelid. | 1B: Eversion of the right upper eyelid reveals an elevated, vascular, pigmented subconjunctival mass |

|

|

| 2A: Additional slit lamp views under tangential lighting conditions reveal the elevated nature of the pigmented subconjunctival mass | 2B: Slit beam view |

|

|

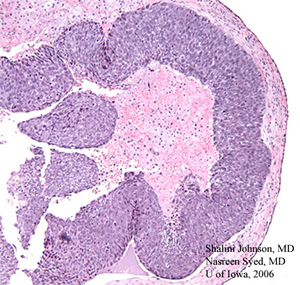

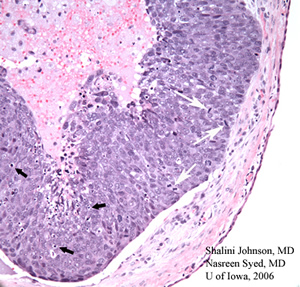

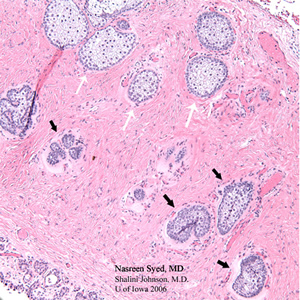

Course: The patient underwent an excisional biopsy that revealed a diagnosis of poorly differentiated Sebaceous Cell Carcinoma on histopathology. He subsequently underwent maps biopsies and a right upper eyelid wedge biopsy which showed atypical Meibomian glands consistent with Sebaceous Cell Carcinoma. He had a final wedge resection which showed no residual Sebaceous Cell Carcinoma. The histopathologic findings are demonstrated in the following photomicrographs.

| 3A: H & E stained section (50x) from the initial excisional biopsy shows comedo pattern of a poorly differentiated sebaceous cell carcinoma | 3B: Higher magnification of the same H & E stained section (200X) demonstrates mitotic figures (white arrows) and apoptotic bodies (black arrows) within the poorly differentiated sebaceous cell carcinoma lesion |

|

|

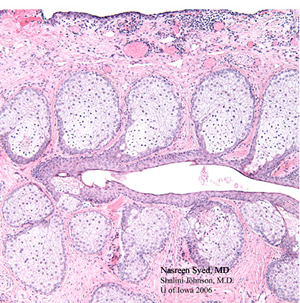

| 4A: H & E stained section of the first eyelid wedge specimen reveals sebaceous cell carcinoma in the lower field of this photomicrograph with atypical dark, pleomorphic sebaceous cells (black arrows). These are in marked contrast to the normal foamy sebaceous glands (white arrows) seen in the upper field of this photomicrograph. | 4B: H & E stained section of the second eyelid wedge specimen demonstrates no residual sebaceous cell carcinoma and shows normal sebaceous glands (Meibomian glands) arranged vertically and draining into a common Meibomian duct. |

|

|

Discussion: Although sebaceous glands are found throughout the body, sebaceous cell carcinoma is found most frequently in the ocular region, which accounts for 75% of cases. The parotid gland is the most common site outside the ocular region, accounting for about 20% of cases. There are five areas in the periorbital region that contain sebaceous cells:

Sebaceous Cell Carcinoma can arise from any of these types of sebaceous glands. However, classically it arises from the Meibomian glands of tarsal plate and from the upper eyelids, which accounts for approximately 2/3 of cases. Less commonly, it is found in the Glands of Zeiss and the lower eyelids. It is rare to find the lesion in the caruncle or eyebrow and very rare to find it in the lacrimal gland, which accounts for only a handful of poorly differentiated cases.

In general, sebaceous cell carcinoma is more frequent in women than in men and affects an older population, usually in the 6th to 7th decade of life. If it presents in younger individuals (< 40 y/o) there is usually a history of radiation for cavernous hemangioma, retinoblastoma or other lesions. Overall, sebaceous cell carcinoma is an uncommon tumor in the United States and accounts for only 0.2-0.7% of all eyelid tumors and 5% of all eyelid malignancies. So it is the second most common eyelid malignancy after basal cell carcinoma, which accounts for a greater bulk (90%) of all eyelid malignancies. Interestingly, there is an increased incidence in China and India where it also is the second most common eyelid malignancy but accounts for approximately 1/3 of all eyelid malignancies (Ni and associates, 1982, Abdi et al., 1996).

Although sebaceous cell carcinoma is one of the most malignant lesions of the eyelids, it may be difficult to diagnose. This is demonstrated by the fact that the average intervening time between presentation and diagnosis ranges from one to three years. The reason for this difficulty in diagnosis is due to its varied presentation both clinically and histopathologically. It tends to masquerade as more common benign conditions, mimicking other tumors as well as inflammatory conditions. Consequently sebaceous cell carcinoma is known to masquerade other conoditions. So it is important to include sebaceous gland carcinoma in the differential diagnosis of most eyelid masses and recurrent inflammatory conditions.

The clinical presentation may vary across a wide spectrum. The most common presentation is a small, rubbery, firm nodule that looks like a chalazion. This is complicated by the fact that sometimes there is true chalazion formation secondary to obstruction of the Meibomian ducts by a mass. The mass may be yellow in color due to its lipid content, especially as it encroaches on the epidermal surface. The mass may also be papillomatous. Less commonly, it presents as diffuse tarsal thickening with associated signs of eyelash misdirection and madarosis. The eyelashes fall out due to the invasion of the eyelash hair follicles. The caruncle is an unusual location for this tumor, but here it presents as a multi-lobulated, grey-yellow subconjunctival mass covered with epithelium. When arising from the glands of Zeis, the lesions form small yellow nodules in front of the gray line and this in turn results in entropion of the eyelid. Besides presenting as various masses, sebaceous cell carcinoma also present as various inflammatory conditions. This results from the intraepithelial spread that is typical of this lesion. Pagetoid spread, characteristic of sebaceous gland carcinoma, occurs when individual tumor cells migrate up to the epithelial surface and form patchy, skip lesions separate from the original tumor mass. This causes irritation and leads to inflammatory presentations such as blepharoconjunctivitis or keratoconjunctivitis. These inflammatory presentations can be associated with ulceration and crusting and may be present for months or even years before a mass is clinically apparent. In addition to presenting as other disease entities, sebaceous cell carcinoma may also present as other tumors. It can present as a gray-white, umbilicated nodule simulating basal cell carcinoma, as a pedunculated keratinizing lesion simulating a cutaneous horn or as a mass in the lacrimal fossa simulating a lacrimal gland tumor.

Another part of the clinical presentation is Muir-Torre syndrome, which includes the association of sebaceous gland tumors or keratoacanthomas with the development of coexistent distant primary malignancies, most commonly colon carcinoma (47%) followed by genitourinary malignancies (21%) and others. This syndrome develops in 25-59% of patients, more often in males than females (2:1) and is surprisingly more commonly associated with the benign variants of the sebaceous tumors. There is a family history in 70% of cases of Muir-Torre syndrome which is associated with a mutation in DNA mismatch repair genes of chromosome 2p and 3p. The transmission is most likely autosomal dominant.

Similar to its varied clinical presentation, sebaceous cell carcinoma may also mimic other disease processes histopathologically. Sebaceous carcinoma may have focal areas of squamous differentiation and is therefore commonly mistaken for squamous cell carcinoma. In fact, 50% of sebaceous cell carcinomas are misdiagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma. Basal cell carcinoma on the other hand can have areas of sebaceous differentiation. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma has clear mucinous cells that resemble sebaceous cells. Melanoma may also simulate sebaceous cell carcinoma since a previously excised melanoma may recur as a nonpigmented lesion in the conjunctiva or cornea.

In terms of pathology, there are different classifications for sebaceous cell carcinoma. One classification involves the degree of differentiation. The well-differentiated lesion demonstrates a high degree of sebaceous differentiation especially in the center of the lesion. The moderately differentiated lesion demonstrates only a few patches of sebaceous differentiation and the poorly differentiated variant demonstrates cells with scant cytoplasm and prominent, pleomorphic nuclei. Another classification is based on the pattern of growth, which has no prognostic significance. The lobular pattern has well-delineated lobules of varying size and demonstrates basaloid features. The comedocarcinoma pattern, which is seen in rapidly growing tumors, has large lobules with areas of conspicuous central necrosis. The papillary pattern, usually seen in the conjunctiva, has papillary fronds that resemble carcinoma or squamous cell papilloma and the mixed pattern is a combination of any of the above three patterns. The final classification pertains to infiltrative capacity and is divided into minimally infiltrative versus highly infiltrative lesions.

A characteristic feature of sebaceous cell carcinoma is the way it infiltrates. Intraepithelial spread or pagetoid spread is reported in 44-80% of cases. Pagetoid spread is the infiltration of single tumor cells or nests of tumor cells into the overlying epithelium. When this infiltration becomes confluent it is called Bowenoid change. Sebaceous cell carcinoma may also spread through direct extension into adjacent structures such as the intracranial cavity, orbit and paranasal sinuses. These are not considered metastases since there is no lymphatic drainage from the eyelids to these structures. However, the eyelids do have lymphatic drainage to the intraparotid, preauricular and submandibular lymph nodes, which are all potential sites for regional metastases (30%). Distant metastases are possible, but rare and the involved organs include liver, lung, brain and bone.

Since the presentation of sebaceous cell carcinoma is so varied, the differential diagnosis is broad including many distinct disease processes. Clinically, the differential diagnosis includes chalazion, keratoconjunctivitis or blepharoconjunctivitis and other sweat gland tumors. Histopathologically, the differential diagnosis includes squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma and melanoma.

The masquerading feature of sebaceous carcinoma makes it a difficult diagnosis. The frequency of wrong clinical impressions has remained unchanged for the last few decades. So it is extremely important to maintain a high clinical suspicion. There are some clues in history and physical that help raise clinical suspicion. A chalazion that presents late in life without a prior history or a recurrent chalazion is quite suggestive. Further investigation is also warranted for inflammatory presentations such as blepharitis or keratoconjunctivitis that are unresponsive or only partially responsive to treatment. Clues on physical exam that should raise suspicion include a diffuse lesion or thickening and madarosis. Histopathologically, special stains such as oil-red-O may be helpful in the diagnosis. However, this requires fresh or wet tissue since paraffin processing washes out lipid.

As with any other lesions, initial management for sebaceous cell carcinoma includes a comprehensive history and physical exam. It is also important to perform baseline lab studies to rule-out metastatic disease. The management of choice for the lesion itself is surgical excision with wide margins, even wider than that which is usually taken for a nodular basal cell carcinoma. The margins may be confirmed by frozen section or Mohs surgery, but these methods are not reliable in detecting intraepithelial spread due to suboptimal detail. Therefore, the preferred method of confirming margins is through permanent sections. So, most oculoplastic surgeons conduct the excisions over a few days and postpone the reconstruction for later. Before performing any surgery, however, conjunctival map biopsies are recommended. This is a way of determining the extent of the lesion and detecting pagetoid spread. These conjunctival map biopsies are recommended irrespective of the clinical picture even if there is no blepharoconjunctivitis-like picture that would suggest intraepithelial spread. The procedure involves sampling representative areas throughout the conjunctiva. Usually 4 biopsies are taken from the tarsal conjunctiva, 6 from the bulbar conjunctiva and 1-4 are taken from the limbus. The biopsies are small and should not require sutures. Each biopsy should be placed in a separate container and accompanied by a diagram or map of where the biopsy was taken. If intraepithelial spread is detected, management is controversial. The options include either exenteration or more tissue sparing alternatives such as cryotherapy or topical chemotherapy with Mitomycin C. Pilot studies done by Shields et al. (2002) and Lisman et al. (1989) show promising results, but further studies are needed. Because of the characteristic intraepithelial spread it is also important to monitor the lacrimal gland system. If there is orbital invasion or diffuse, bulky lesions on both eyelids, exenteration is indicated. Radiation is reserved only for poor surgical candidates since it is associated with a high rate of recurrence. There are some case studies, however, that show success with high dose radiation of >55 Gy. Since regional metastases are possible it is important to check for lymph node involvement through fine needle aspiration biopsy and to continue monitoring for submandibular, preauricular and cervical lymphadenopathy. Although rare, it is also important to evaluate for Muir-Torre syndrome. Recommended evaluation includes rectal examination, colonoscopy or barium enema and cytologic analysis of first morning urine.

Sebaceous cell carcinoma is an aggressive tumor seen most often on the eyelid. Since it clinically mimics other disease it is difficult to diagnose. However, accurate and prompt diagnosis is crucial since it is not only one of the most malignant lesions on the eyelid, but also one with serious associations such as Muir-Torre syndrome and high potential for regional and distant metastases. Since it is seen almost exclusively on the eyelid, the burden for maintaining high clinical suspicion and making this challenging diagnosis falls on the ophthalmologist and ocular pathologist.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT

|

Johnson S, Nerad JA, Syed NA. Sebaceous Cell Carcinoma: A Masquerade Syndrome. EyeRounds.org. January 23, 2007; Available from: http://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/cases/eyeforum/62-Sebaceous-Cell-Carcinoma-A-Masquerade-Syndrome.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.