Chief Complaint: 52-year-old female with red left eye.

History of Present Illness: 52-year-old female with an upper respiratory tract infection for several days called the resident on-call at the University of Iowa because of a red left eye. She was especially concerned because she had a trabeculectomy with mitomycin C (MMC) two years previously and was informed to call immediately if she ever developed redness, irritation, or decreased vision in her left eye. She had experienced no pain or visual changes.

Past Ocular History: Primary open angle glaucoma, myopia, cataracts, and pinguecula in both eyes (OU). History of trabeculectomy with MMC, left eye, as noted.

Medical History: Migraines, hypercholesterolemia, insulin dependent diabetes mellitus without diabetic retinopathy.

Medications: Topical drops included latanoprost at bedtime in the right eye (OD) and brimonidine twice daily, OD. Systemic medications include insulin, sumatriptan, baby aspirin, and atorvastatin. No known drug allergies.

Family History: Significant for glaucoma.

Social History: Occasional alcohol consumption. No tobacco use.

|

|

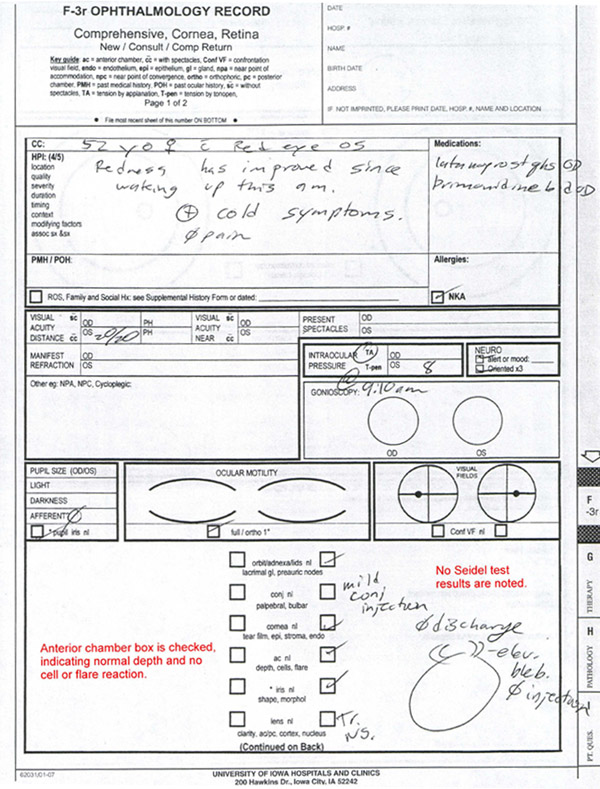

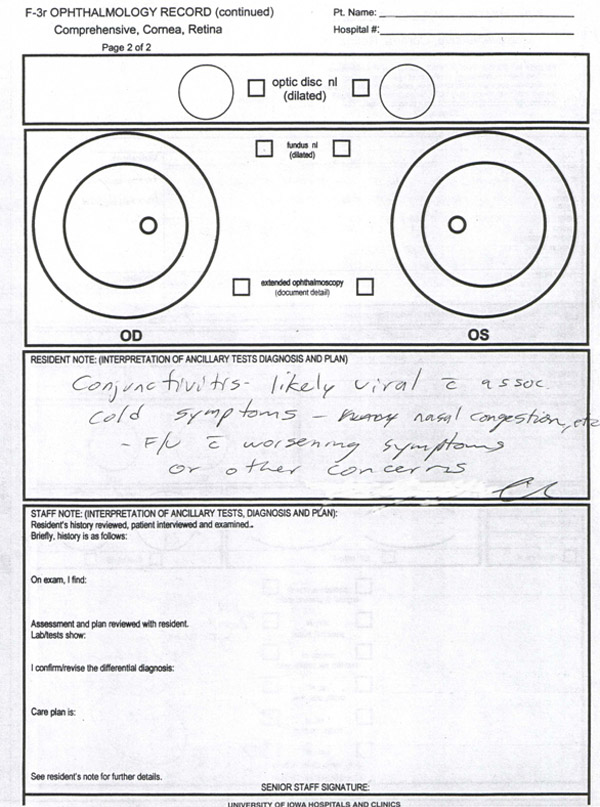

Course: The patient was instructed to come to the eye clinic immediately after calling the resident on-call. After reviewing her history and exam, the resident felt that there was no evidence of blebitis or endophthalmitis and concluded that she was most likely suffering from viral conjunctivitis, which was likely associated with her upper respiratory tract infection. The patient went home but returned two days later with worsening symptoms, which included mattering and similar symptoms in her right eye. She was again examined and the same diagnosis was given, however the attending physician was disappointed with the above note (see Figures 1 & 2). Specifically, he felt that the resident’s exam did not contain an adequate description of the pertinent negatives of no cell or flare reaction and negative Seidel testing.

Discussion: Professionalism is one of six areas that the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires residents to become competent in during the course of their residency (ACGME, 2006). Professionalism should be evaluated by measurement of specific knowledge, skills, behaviors, and attitudes that manifest "a commitment to carrying out professional responsibilities, adherence to ethical principles, and sensitivity to patients of diverse backgrounds (ACGME, 2006)."

In an effort to further delineate the specific aspects of professionalism, The American Academy of Pediatrics outlined eight components of professionalism: honesty/integrity, reliability/responsibility, respect for others, compassion/empathy, self improvement, self awareness/knowledge of limits, communication/collaboration, and altruism/advocacy (Klein, 2003). Appropriate medical documentation is a component of professionalism and therefore an important part of resident education. Residents need to understand that the medical record serves many purposes in addition to the recording of data obtained during the clinic visit. Medical records serve as a means of communication among the various parties involved in the care of the patient. In this regard, it is important to consider the perspective of those who may be expected to read the medical record while making appropriate documentation.

In this case, the attending physician became concerned when he learned that his post-trabeculectomy patient had developed a red eye and was sent home, without evidence of a more extensive examination with documentation of the negative exam findings (ie., no cell or flare in the anterior chamber and negative Seidel testing). While the box indicating a "Normal AC" was checked, it would have been more reassuring to have these negative finding written separately. Documentation of negative findings provides reassurance, but more importantly, it improves communication among the care team and increases the level of professionalism.

Communication through medical documentation is an important aspect of resident education that is learned through experience and educational activities dedicated to this purpose. This is why ophthalmology residency programs have been asked by the ACGME to "provide educational experiences as needed in order for their residents to demonstrate [professionalism]", and the other competencies (ACGME, 2006). Resident documentation has been shown to be fraught with error, with one study showing discrepancies in 62% of daily progress notes in the neonatal intensive care unit (Carroll, 2003). In this light, it is easy to see why an attending physician could be concerned with resident documentation which entails a check mark in the "normal" box.

Examination and documentation of the postoperative patient: The examination of postoperative patients requires special attention to specific components of the eye exam. Documentation of the visit should emphasize these areas, in order to reassure the reader that these aspects of the exam were each considered and evaluated. A complete examination includes examining the visual acuity (VA), refraction, pupils, motility, visual fields, intraocular pressure (IOP), anterior segments (by slit lamp), and posterior segments (by indirect ophthalmoscopy). However, in postoperative patients, special consideration should be given to the following specific aspects of the complete exam (Arnold, 2006):

Anterior segment surgery: Visual acuity (VA), IOP, anterior segment exam including evaluation of the surgical site with Seidel testing, anatomy of the anterior segment, position of an intraocular lens (IOL), evaluation of filtering blebs or stents and their position. Additionally, evaluation for any anterior chamber reaction, hyphema, or hypopyon should be carefully documented.

Retinal/Vitreous surgery: VA, IOP, anterior segment exam, and posterior segment exam. Evaluation of the retina should include assessment of whether it is attached, presence of any subretinal fluid, evaluation of any holes, breaks, or tears and their associated treatment. Often patients will have an intraocular gas bubble, which should be evaluated for size and position.

Strabismus surgery: VA, IOP, and motility to check for proper reattachment of muscles and function. Additionally, the anterior segment exam should look for evidence of anterior segment ischemia, scleral perforation, or infection.

Eyelid and Orbital surgery: VA, examination of surgical wounds including proper apposition and evidence of infection including erythema, presence of discharge, or abnormal tenderness. Lid position should be closely evaluated, especially after ptosis, entropion, ectropion, and tumor resection surgery. Following orbital surgery, evaluation of extraocular muscle function should be assessed. Additionally, evidence of retro-orbital bleeding should be documented including measurements of any proptosis, motility restriction, and IOP.

Laser surgery: While laser procedures tend to alter the anatomy less than other surgeries, certain components of the exam are essential to identify possible complications. Checking the VA and IOP for possible pressure spikes is necessary. Additionally, evaluation of the success of the treatment is important. Corneal abrasions and/or edema are common complications after many laser procedures. Additionally, macular edema and retinal detachments can occur after laser treatments, necessitating a thorough retinal evaluation.

Key Point: Documentation as an element of Professionalism. Documentation of significant negative exam findings.

Fillmore PD, Oetting TA, Alward WLM. Professionalism: Documenting Pertinent Negatives. EyeRounds.org. August 10, 2007; Available from: http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/71-Documenting-Pertinent-Negatives-ACGME.htm.

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.