Chief Complaint: 51-year-old male with "difficulty focusing" in the left eye (OS).

History of Present Illness: A 51-year-old male presented in December 2002 with 3-month history of difficulty focusing and floaters in his left eye. Relevant past ocular history included four retinal detachment repair procedures on the right eye between April and July 2002.

Past Ocular History: 4/01: Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment right eye (OD) repaired with scleral buckle placement (SBP); 6/01-7/01: Recurrent retinal detachments OD (3 weeks apart) repaired with Pars Plana Vitrectomy (PPV) x 3 and Pars Plana Lensectomy by 2 different surgeons ("limited" choroidal heme with the second PPV, silicone oil with the last PPV).

Medical History: Ankylosing spondylitis, arthritis, hypothyroidism

Medications: Systemic medications include Synthroid, Sulindac, Nitro-Dur, and Aspirin. Drops in the OD include Cosopt bid, Erythromycin bid, Lumigan qhs.

Family History: The patient's mother has glaucoma, father has macular degeneration, and a son had retinal detachments at ages 11 and 14.

Social History: Occupation- farmer; Denies alcohol and tobacco use

Review of Systems: Negative, except as noted above.

Ocular Examination:

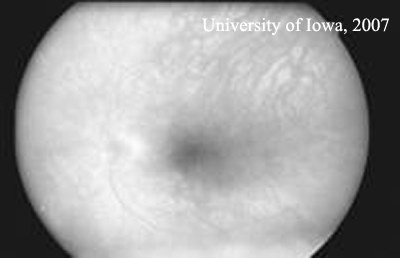

| Figure 1A: Right Fundus. There is extensive laser and post-surgical change. There is no active inflammation and the retina remains attached. | Figure 1B: Left fundus. Inflammatory, punctate chorioretinal lesions are seen in the mid-periphery (Dalen-Fuchs' nodules) |

|

|

| Figure 1C: Fluorescein angiogram, OS. No leakage is visible. | |

|

Course: The appearance of white spots in the fundus of the left eye raised the possibility of sympathetic ophthalmia (SO). However, the good visual acuity, lack of vitreous cell, no signs of leakage on fluorescein angiography, and normal choroidal thickness all argued against active ophthalmia. SO was explained to the patient and aggressive steroid therapy was recommended if he developed any signs or symptoms.

In January 2002, the patient returned for his 2-week follow up exam. He reported persistent problems with accommodation, but no decrease in vision. On exam, his visual acuity was bare light perception OD; OS was 20/25. Ocular exam of the right eye was unchanged, but new finding in the left eye included: anterior vitreous cells in the left eye and more prominent yellow subretinal nodules in the midperiphery. The new finding of vitreous cells increased the concern for SO. Baseline labs were obtained (CBC, ESR, ACE, and RPR) and the patient was started on Prednisone 80 mg/day and topical Prednisolone acetate (PF) 1 drop OD QID. One week after starting the prednisone, the patient reported a big improvement. His floaters had improved and he was able to read much more easily. On exam, VA in his right eye was no light perception and 20/20 in the left eye. There was no change in slit lamp exam of the right eye and the left eye had a few anterior vitreous cells and numerous yellow white punched out lesions in the mid peripheral retina that appeared more atrophic than they did the previous week. The lab results came back normal, but both the PPD and the controls that had been placed were nonreactive. After discussion, the patient agreed to proceed with enucleation of his right eye. Enucleation was recommended for both a comfort standpoint (the eye had no light perception and a persistent epithelial defect and would likely to become painful in the future) and to give a histopathologic diagnosis that might guide further management.

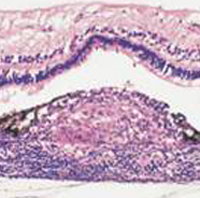

In February of 2002 the patient underwent enucleation of the right eye. The pathology was consistent with Sympathetic ophthalmia (see Figure 2).

| Figure 2: Pathology - Histologically, in sympathetic ophthalmia lymphocytes (initially CD4 cells, later CD8) cells infiltrate the uvea resulting in lymphocytic infiltration and the formation of granulomas. Deposition of these granulomas between Bruch's membrane and the RPE is termed a Dalen-Fuchs' nodule. In our patient, there was almost complete loss of retinal architecture in many areas. |

|

In February 2002, visual acuity was 20/20, but Goldmann visual field showed an enlarged blind spot. Fluorescein angiogram demonstrated staining of the punctate spots in the peripapillary region, but no significant leakage. Given the blind spot enlargement, the patient received a sub-Tenon’s steroid injection and Imuran was started. His VA remained 20/20 until June 2002 when it dropped to 20/50 with IOP 34 and corneal edema. Cosopt was added to try to lower the steroid-induced elevation in intraocular pressure. Imuran was switched to Cyclosporine (CSA) and Prednisone was continued at 12.5 mg/day. From June to August 2002, his VA 20/40- 20/60, IOP low 30’s. On 9/25/02 , he underwent a glaucoma filtering procedure (Trabeculectomy with MMC). In February 2003, he underwent cataract extraction with intraocular lens placement, intraocular Kenalog was injected, CSA and prednisone were continued and PF was tapered to bid. The patient’s symptoms continued to recur whenever his Prednisone was tapered below 20mg per day. A RETISERT™ intravitreal implant (fluocinolone acetonide) was implanted OS 9/05 after which he had no further flares. His visual acuity is still 20/20 and visual fields are stable in 12/07.

Comment: Sympathetic ophthalmia, although rare, is a potentially visually devastating disease. The patient that we have presented developed sympathetic ophthalmia following repeated vitreoretinal surgery without a history of accidental trauma. Prompt and effective management with systemic immunosuppressive agents permitted control of his disease and retention of good visual acuity in the remaining eye. Vitreoretinal surgery should be viewed as a possible inciting event for sympathetic ophthalmia. Successful vitrectomy does not preclude the development of sympathetic ophthalmia and any persistent uveitis following vitrectomy should alert the ophthalmologist to the possibility of the development of sympathetic ophthalmia.

Definition: Sympathetic ophthalmia (SO) is a rare bilateral granulomatous panuveitis that follows accidental or surgical trauma to one eye. The injured eye is referred to as the exciting eye, whereas the uninjured fellow eye is termed the sympathizing eye.

History: Sympathetic ophthalmia was known to Hippocrates over 2000 years ago. The first written reference to sympathetic ophthalmia appeared about 1000 A.D. stating that "[t]he right eye, when diseased, often gives suffering to the left." In the 16th century, Bartisch wrote that after injury in one eye, "the other good eye is in great danger." The term sympathetic ophthalmia was coined in 1830 by MacKenzie, who presented 6 cases of penetrating wounds in one eye with development of inflammation in the other eye within three weeks to one year. MacKenzie postulated that the inflammatory process spread from the exciting to the sympathizing eye via the optic nerve and the optic chiasm. In 1905, Ernest Fuchs provided the classic histologic description of SO. He described a mixed-cell inflammatory infiltration of the uveal tract particularly affecting the choroid. He and Dalen independently described the inflammatory nodular aggregates (Dalen Fuchs nodules) that now bear their names. In 1910, Elschnig proposed that an autoimmune inflammatory response against uveal antigens is the etiology.

Incidence and Epidemiology : Estimates of the incidence of SO vary from 0.2% to 0.5% following accidental ocular trauma and 0.01% following ocular surgery. However, these estimates are based on retrospective studies, with clinical data often more than 10 years old, and may not reflect the benefits of modern microsurgical techniques and immunosuppression. In 2000, a prospective study from the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland estimated that 3 out of every 10,000,000 cases of penetrating injury or surgery resulted in SO.

Formerly, accidental penetrating trauma was the most common precipitating event for SO. A recent report suggests that ocular surgery, particularly vitreoretinal surgery, has now become the main risk factor for SO (according to a prospective study in the UK by Kilmartin et al and a retrospective study at the National Eye Institute in the US by Chan et al.). Ophthalmologic surgical procedures that have been reported to cause SO include cataract surgery, glaucoma filtering procedures, scleral buckling, laser cyclophotocoagulation and proton beam irradiation for choroidal melanoma. In the early 1980s, the prevalence of SO following pars plana vitrectomy was reported to be 0.01%, increasing to 0.06% when performed in the context of other penetrating ocular injuries. Recent studies suggest that the risk of developing SO following pars plana vitrectomy is more than twice this figure and may be significantly greater than that of infectious endophthalmitis following vitrectomy(0.05%). The etiologic shift from accidental trauma to surgical trauma can partially be explained by the improved access to emergency surgical care following accidental trauma. In addition, retinal surgery is being performed with increasing with newer techniques and expanding indications.

A shift in the demographics of SO has also been suggested in a recent report. Retrospective case series found SO to be more likely to occur in males, children, and the elderly (due to increased risk of accidental trauma). However, a recent report showed no sex predominance and a lower risk in children (probably because of a reduced role of accidental trauma and fewer eye injuries in children) and an increased risk in the elderly (likely because of increased frequency of ocular surgery, and possibly because of increased frequency of retinal detachment in the elderly).

Onset: The length of the latent interval between perforation and inflammation of the non-injured or sympathizing eye is very variable. SO may occur as early as 10 days or as late as 50 years following the suspected triggering incident. Early reports suggest that SO developed in 80% of patients within 3 months of injury and in 90% within 1 year. However, the time interval between initial injury and disease onset may be longer than traditionally thought. In a recent series, 33% of patients developing SO within 3 months of initial injury and less than half developing SO within 1 year of injury.

Clinical features: Patients with SO typically present with asymmetric bilateral panuveitis, with more severe inflammation in the exciting eye than in the sympathizing eye, at least initially. Symptoms range from minimal to severe and include problems in near vision (accommodation), photophobia, floaters and decreased vision. Initial anterior segment findings include mutton-fat keratic precipitates on the corneal endothelium, posterior synechiae formation, and elevated IOP (uveitic glaucoma). Initial posterior segment findings include vitritis, Dalen-Fuchs nodules (yellowish white mid-equatorial choroidal lesions), peripapillary choroidal lesions and exudative retinal detachment. Chronic SO can lead to cataract formation, chronic CME, choroidal neovascularization, and optic atrophy. Extraocular findings including sensorineural deafness, alopecia, poliosis and vitiligo are rare, but well recognized features of SO

Eyes with sympathetic ophthalmia have characteristic patterns of fluorescein angiography (FA). In the acute stage of the disease, FA reveals multiple hyperfluorescent sites of leakage at the level of the RPE during the venous phase. In severe cases, these foci may coalesce, with pooling of dye observed beneath areas of exudative retinal detachment. The sites of clinically observed Dalen-Fuchs nodules appear hypofluorescent early followed by late staining, simulating the pattern seen in acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE). It is probably the status of the pigment epithelium overlying the Dalen-Fuchs nodules or the integrity of the choriocapillaris that determines the hyperfluorescent or hypofluorescent nature of these lesions of FA. The optic nerve head may demonstrate leakage in the later stages of the angiogram. B-scan ultrasonography can be used to demonstrate the marked choroidal thickening seen in cases of SO.

Pathology and Pathogenesis: The histopathology of the inflammatory changes in SO are identical in the exciting and the sympathizing eyes.

Histologically, a diffuse granulomatous inflammatory reaction appears within the uveal tract composed of lymphocytes and epithelioid histiocytes containing phagocytosed melanin pigment. Typically, the choriocapillaris is spared. Varying degrees of inflammation may be present in the anterior chamber as evidenced by histiocytes deposited on the corneal endothelium (mutton-fat keratic precipitates). Dalen Fuchs nodules, which are collections of epithelioid histiocytes, depigmented retinal pigment epithelial cells and lymphocytes between the RPE and Bruch’s membrane, are present in about one third of eyes.

Immunohistochemical techniques have been used to show that CD4+ T lymphocytes are important early in the disease with CD8+ lymphocytes evident later. These changes in T-cell subsets over time may reflect a dynamic situation in which there is an attempt to down-regulate the immune response with the influx of suppressor T cells.

Etiology: The concept that an autoimmune inflammatory response is the basis of this disorder was proposed by Elschnig in 1910. He proposed that uveal pigment was the putative antigenic stimulus. Although the precise autoantigen responsible is still inconclusive, retinal S-antigen, interphotoreceptor retinoid binding protein, melanin associated antigens, and antigens derived from the RPE and choroid have all been implicated. Induction of uveitis with the ocular antigens interphotoreceptor retinoid binding protein and S-antigen produces a disease in monkeys that has many of the characteristics of SO, including the development of Dalen Fuchs nodules.

Role of the Penetrating Wound: Clinical observations have established that sympathetic ophthalmia develops after a penetrating wound but not subsequent to often more severe intraocular disturbances such as extensive photocoagulation. A feature of the penetrating wound that appears important in the pathogenesis of SO is the access it provides for intraocular antigens to reach regional lymph nodes. The intraocular compartment has no lymphatic drainage and appears to function like a number of alymphatic biologic sites. In an experimental model of SO, To study the role of the penetrating wound in the development of SO, Rao and colleagues used the retinal S-antigen uveitis model to compare intraocular antigen presentation with extraocular antigen presentation and found that subconjunctival injection of retinal S antigen in one eye induced a bilateral sympathetic uveitis, whereas intraocular injection in one eye was ineffective in inducing sympathetic disease. The authors suggested that the penetrating wound participated in the development of SO by exposing uveoretinal antigens to the conjunctival lymphatics and thereby inducing a subsequent immunopathologic response.

Genetic Predisposition: Why some individuals can have multiple surgeries or traumas and do not mount an inflammatory response while others are more vulnerable remains to be determined, however there may be a genetic predisposition to the development of the disease as patients with SO are more likely to express HLA-DR4, -DRw53, and –DQw3 haplotypes. Recent studies from the United Kingdom and Japan report the highest relative risk for haplotypes HLA-DRB1*04 and –DQB1*04. These same alleles are overrepresented in Japanese and American patients with VKH and in a variety of nonocular autoimmune diseases, lending support to the idea that a genetic susceptibility factor is operative in SO.

Role of Enucleation: The classic teaching has been that severely traumatized eyes should be enucleated within 14 days after ocular injury to protect the second eye from the development of SO. Exceptions to this rule do occur, but are rare.

Controversy exists regarding the advisability of enucleating the exciting eye once SO has commenced. Early reports by Irvine and Winter noted that enucleation of the exciting eye 2 months or more following the onset of sympathetic ophthalmia had no effect on the course of the disease. Lubin and colleagues reported that 74% of patients had 20/70 or better vision in the sympathizing eye if the exciting eye was enucleated within 2 weeks of onset, whereas if enucleation was performed after 6 months, only 50% of patients attained 20/70 or better vision. Lubin et al used a multiple linear logistic regression model to assess the effect of timing of enucleation, degree of inflammation, and corticosteroid treatment on the final visual outcome. The most significant predictive factor was timing of enucleation at less than 14 days. Reynard et al also determined that enucleation of the exciting eye within 2 weeks was associated with a more benign course, and advocated early enucleation. In contrast, Marak contended that early enucleation did not affect visual outcome. Kuo et al also reported that prompt enucleation of the inciting eye reduced the number of exacerbations, but reported that this did not affect the visual outcome.

Also controversial is the role of evisceration vs. enucleation. SO may occur after evisceration, probably as a result of remaining uveal tissue in the scleral emissary channels. Although this risk is small, there is a strong preference for enucleation rather than evisceration amongst ophthalmologists.

Enucleation should be considered only when the eye has no discernible visible functions and the visual prognosis is nil. Removal of eyes with useful vision is not recommended. If sympathetic ophthalmia occurs, the traumatized eye may eventually be the one with the better visual acuity.

Medical Treatment: Immunomodulatory therapy, initially with systemic corticosteroids, with later addition of corticosteroid-sparing agents (azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, chlorambucil, and cyclophosphamide) is the mainstay of therapy for SO. Systemic steroids are recommended on a daily basis, beginning with a high dose of a short-acting agent (e.g. 1.0 to 1.5 mg/kg/day prednisone).Topical corticosteroids, together with cycloplegic/mydriatic agents are essential in treatment of acute anterior uveitis associated with SO as are periocular corticosteroids in the management of inflammatory recurrences and CME. As all of these immunosuppressive agents can have significant systemic side-effects, collaborative management with an internist, rheumatologist or hematologist is advisable.

Prognosis: The relapsing nature of SO and the potential toxicity of treatment modalities warrant a careful long-term follow up of patients with this disease. Spontaneous improvement rarely occurs and if left untreated, SO leads to loss of vision and phthisis bulbi. The use of corticosteroid and other immunosuppressive agents together with the advancements in microsurgical techniques for wound repair have improved the prognosis of SO, with 50% of patients achieving a final visual acuity of 20/40 or better in at least 1 eye. Cataract, secondary glaucoma, and chronic maculopathy are the major causes of visual loss.

| TREND | HISTORICAL | CURRENT |

|---|---|---|

| Cause | Post trauma | Post surgery (esp. vitreoretinal) |

| Patients | Males and children (reflecting trauma peaks) | No gender preference (reflects positive impact of injury prevention programs) and increasingly elderly patients (reflects impact of ocular surgery) |

| Incidence | Considered disappearing 30 years ago | Probably increasing (under-diagnosed?) |

| Onset | For 65%, within 2-8 weeks; for 90% < 1yr | Many delayed presentations as well |

| Presentation | Granulomatous panuveitis | Any clinical uveitis |

| Inciting Eye | Enucleation within 2 weeks of trauma for prevention of SO | Enucleation solely for the prevention of SO is questionable |

| Visual Prognosis | Poor | Reasonable due to modern immunosuppression |

Sympathetic ophthalmia is a clinical diagnosis depending essentially on the history of ocular injury by surgery or trauma followed by bilateral uveitis. Occasionally, it may be difficult to distinguish sympathetic ophthalmia from Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome, but patients with VKH have no history of trauma. Patients with VKH typically have bilateral localized serous detachments of the retina, which are not seen in SO. VKH is also more prevalent amongst Asians and African Americans and extremely rare in patients of northern European extraction. If it is necessary to differentiate the syndrome from VKH, a lumbar puncture should be performed early in the course of the disease. This reveals a pleocytosis with mostly lymphocytes and monocytes in 84% of cases of VKH. Sarcoidosis, when it produces multiple small foci of choroiditis, may also (rarely) be confused with sympathetic ophthalmia.

| Sympathetic Ophthalmia | Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Syndrome | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | All ages | 20-50 years of age |

| Racial predisposition | None | Asian and Black |

| Penetrating trauma | Almost always present | Absent |

| Skin changes | Uncommon or unrelated | Common (60-90%) |

| CNS findings | Uncommon | Common (85%) |

| Hearing dysfunction | Uncommon | Common (75%) |

| Retinal serous detachment | Uncommon | Frequently seen |

| Choriocapillaris involvement | Usually absent | Frequently seen |

| CSF findings | Usually normal | Pleocytosis (84%) |

EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT

|

Pham LTL, Graff JM, Gehrs KM. Changing Trends in Sympathetic Ophthalmia: Sympathetic ophthalmia following repeated vitreoretinal surgery with no history of trauma. EyeRounds.org. February 13, 2008; Available from: http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/81-Sympathetic-Ophthalmic-Intraocular-Surgery.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.