Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) & Implications for the Eye

Authors: Tucker Dangremond, BS; Austin Fox, MD; Pavlina Kemp, MD; Thomas Oetting, MD

Posted April 15, 2020

Introduction

Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses, represented by illnesses such as the common cold, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS), and now the virus causing Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). In December 2019, this novel coronavirus was identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China and was subsequently coined severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by the Word Health Organization.

SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus which is highly transmissible. The virus has rapidly spread across the globe, resulting in the first global pandemic since the 1918 H1N1 influenza outbreak which resulted in at least 50 million deaths [1]. Though our understanding of the disease continues to evolve, this article intends to serve as a reference for eye care and other healthcare providers, including a summary of basic disease characteristics, known ophthalmologic associations, and best-practice guidelines for management of ophthalmologic practices in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Epidemiology

Geography

The first cases of COVID-19 were reported in Wuhan, Hubei, China in late December 2019, and the epidemic peaked and plateaued in China between late January and early February 2020 [2]. The virus initially spread to more affluent countries, carried by infected individuals via air travel. On January 19, 2020, the United States reported its first case of COVID-19, and as of March 26, 2020 had the highest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases of any country in the world [3]. Numerous countries in Western Europe and Iran have also reported staggering numbers of cases and deaths, and now almost all countries in the world have reported cases of COVID-19. The case numbers and death tolls continue to rise, and updated information on spread can be found at the WHO website.

Transmission

Spread of the virus is thought to occur primarily through respiratory droplets, with viral particles being transferred between individuals in respiratory secretions when an infected individual coughs, sneezes or talks. However, it is likely that this is not the only route of transmission. There is also evidence that transmission may occur directly via direct contact or indirectly through contact with a fomite (a virus-contaminated object such as a stethoscope) [4], aerosolization [5], or through fecal-oral transmission [6]. Though still under investigation, it is theorized that the virus may also be transmitted though the ocular surface [7]. One study has shown that SARS-CoV-2 nucleotides have been detected from conjunctival swabs of patients with COVID-19 [8], however another small study did not find SARS-CoV-2 nucleotides in tears from 17 patients with COVID-19 [9].

Rates of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 have been shown to vary based on location, infection control interventions and patient symptomology. In China, the rate of developing secondary COVID-19, obtained through contact tracing of tens of thousands of individuals who interacted with confirmed COVID-19 patients, was reported to be 1 - 5 % [2]. The R0, or basic reproduction number, represents the expected number of secondary cases resulting from one infectious case and is often used to quantify the intensity of an outbreak. R0 for COVID-19 has been estimated to be 5.7, meaning that each COVID-19 patient can be expected to infect an average of 5.7 other individuals which represents an exponential increase [10].

Transmission from asymptomatic individuals, as well as transmission prior to symptom onset, has also been reported [11-14], raising concerns that symptom screening, though important, may not be enough to contain the spread of disease.

Incubation

COVID-19 has an incubation period of up to 14 days following exposure with a median of 5.1 days. It has been reported that 97.5% of patients develop symptoms within 11.5 days of infection [15].

General Clinical Presentation

COVID-19 may infect individuals of all ages. In a report of 1099 COVID-19 patients from China, the median age was 47 years [16]. Patients affected by COVID-19 may present with a variety of flu-like symptoms, ranging from asymptomatic carriers to those in severe respiratory compromise. In the report of 1099 COVID-19 patients from China, the following symptoms were reported in order of decreasing frequency:

- Cough (68%)

- Fever (44% at presentation; 89% during hospitalization)

- Fatigue (38%)

- Sputum production (34%)

- Shortness of breath (19%)

- Myalgias/arthralgias (15%)

- Sore throat (14%)

- Headache (14%)

- Chills (12%)

- Less common symptoms included nasal congestion (5%), nausea/vomiting (5%), diarrhea (4%), conjunctival congestion (1%), hemoptysis (1%).

Awareness of these symptoms is important in order to triage patients appropriately in the ophthalmology clinic.

Ophthalmologic Implications

While transmission of SARS-CoV-2 through ocular surfaces remains under investigation, SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been found in tears of some patients with COVID-19 and reports suggest that transmission may occur through the ocular surface [7]. In a study of 38 consecutive patients with COVID-19, conjunctivitis was present in 12 individuals. Interestingly, these 12 COVID-19 patients with conjunctivitis were more likely to have severe respiratory disease. Epiphora was the presenting symptom for one patient [17]. Another case series of 30 COVID-19 patients found that only one patient had SARS-CoV-2 RNA detected in tears and conjunctival secretions [8]. Though transmission of SARS-CoV-2 through the ocular surface has not been definitively established, we suspect that this is possible based on our knowledge of other respiratory viruses [18].

Clinically, COVID-19 has been associated with a bilateral mild follicular conjunctivitis in the few reported cases. It is likely that symptoms manifest similarly to other common forms of viral conjunctivitis. See Adenoviral Conjunctivitis for further information [19].

Treatment of ocular symptoms is supportive, including the use of cold compresses and artificial tears for comfort. Antibiotic and antiviral drops are not routinely used.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine

Treatment for COVID-19 consists primarily of supportive measures. While there are no medications with proven efficacy for treatment or prophylaxis of COVID-19, there are medications which have shown promise in nonrandomized trials. Among these are chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine [20, 21]. The use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine has raised questions regarding the need for baseline fundus exam given the well-established risks of ocular toxicity posed by these medications. Ocular manifestations include retinal toxicity and corneal verticillata (corneal deposits of salts within the corneal epithelium) [22]. While baseline fundus examination and annual dilated fundus examination are important for monitoring patients on long-term therapy, the anticipated duration of treatment in patients taking these medications for COVID-19 is a short period. As such, the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) does not recommend baseline ophthalmologic examination under these circumstances, however AAO encourages physicians to base clinical decisions on available scientific evidence [23] . For further information, see Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) Toxicity and Recommendations for Screening.

Best Practice

Given the evolving information and implications of COVID-19, it is important for healthcare providers including eye care providers to employ infection control strategies while providing care for patients. Eyecare providers must be cognizant of the possibility that patients affected with COVID-19 may present to them with symptoms of viral conjunctivitis. In fact, the AAO warns that given the high prevalence of patients with other forms of conjunctivitis who often present to eye clinics or emergency departments, eye care professionals may be the initial healthcare contact for patients possibly infected with COVID-19 [23]. As such, providers should be aware of the possible risks of transmission when contacting the ocular surfaces and be prepared to report suspected cases of COVID-19 to the appropriate public health authorities.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and AAO have released numerous recommendations for identifying at-risk patients and preventing secondary infection of both patients and providers. These recommendations, along with evidence from relevant studies, have been summarized below. For full and updated details, please visit the CDC and AAO websites.

Screening Questions

The following questions should be asked to identify patients with possible exposure to SARS-CoV-2 [23].

- Does the patient have fever or respiratory symptoms?

- Does the patient have conjunctivitis?

- Has the patient had contact with a suspected or confirmed case of COVID-19 in the last 14 days?

Patient Scheduling

In an effort to reduce the risk of exposure for both patients and providers, the US surgeon general, CDC, and AAO have recommended that efforts should be made by clinicians to postpone unnecessary outpatient visits and elective procedures [23-25]. This includes rescheduling visits for nonurgent ophthalmic problems which do not pose a significant threat of deterioration (of vision) without regular surveillance or intervention.

As providers look to reduce unnecessary patient contact, telemedicine has emerged as a valuable outlet for ensuring continuity of care while maintaining appropriate social distancing. While there are obvious limitations to this approach when it comes to the ophthalmic examination, telephone services, internet-based consultation or telemedicine exam may be useful in continuing to provide valuable care for certain patients. For supportive information, see the AAO guide to Coding for Phone Calls, Internet and Telehealth Consultations.

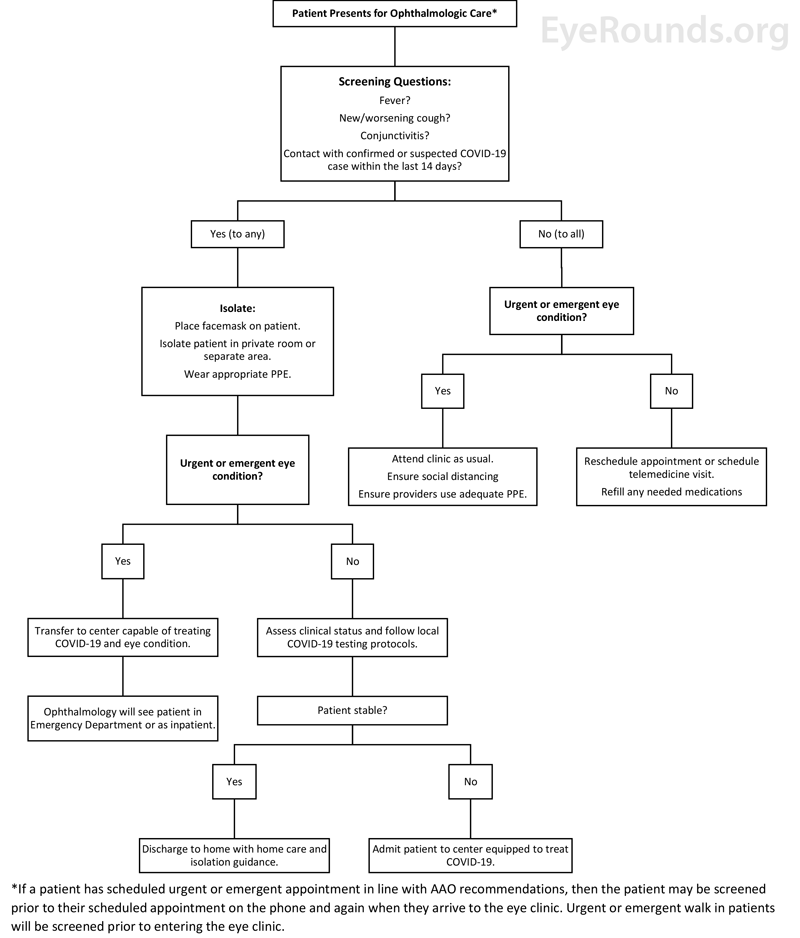

The following strategy to triage patients presenting for ophthalmologic care has been implemented at the University of Iowa and may be useful for other ophthalmology clinics:

Figure 1. Triage flowchart for patients presenting for ophthalmologic care.

Seeing Patients

PPE, Hand Hygiene and Environmental Cleaning

When caring for patients potentially infected with COVID-19, as elicited by the screening questions above or confirmed positive testing, it is imperative that providers protect their mouth, nose, and eyes. While keeping in mind that valuable personal protective equipment (PPE) must be conserved, the following precautions should be taken as resources allow.

- Masks: N-95 respirators provide optimal airway protection from infected respiratory droplets and aerosols. Other masks should be utilized as available in the case of shortages. Additionally, patients who cough, sneeze, or have flu-like symptoms should be provided with masks to wear during examination.

- Eye protection: Given the possible risk of viral transmission through ocular surfaces, face shields or goggles should be worn by providers.

- Slit-lamp breath shields: Slit lamp breath shields can provide an important barrier when examining patients' eyes. Some manufacturers are offering free slit-lamp breath shields to providers via their websites.

- Hand hygiene: The CDC continues to recommend the frequent use of alcohol-based hand rub as the primary form of hand hygiene in most clinical scenarios. This has been shown to reduce the number of pathogens on the hands while also being less damaging to the skin than frequent handwashing. Hands should still be washed with soap and water for at least 20 seconds when visibly soiled, before eating, and after using the restroom [26].

- Sanitation: The use of PPE and proper hand hygiene should be augmented with regular cleaning and sterilization of medical equipment and other office surfaces. Recommended disinfectants include diluted household bleach, alcohol solutions with at least 70% alcohol, and common household disinfectants, such as Clorox brand products, Lysol brand products and Purell professional surface disinfectant wipes.

Outpatient Clinic

As noted above, ophthalmology practices should strive to provide only urgent care to patients during this time. Those patients with COVID-19 who need urgent ophthalmic care should be triaged to hospitals and centers properly equipped to handle both ailments. Efforts should also be made to comply with social distancing in waiting areas by taking steps like removing seating and encouraging patients to wait in other locations (outdoors or in their cars).

Additionally, some common practices in eye clinics may theoretically increase the risk of viral transmission and should be adjusted accordingly. One such example is non-contact tonometry (NCT). NCT is a potential source of microaerosols, and therefore increases the risk of viral transmission from the ocular surface of infected patients. The associated pulses of pressurized air have been shown to disrupt the tear film, causing tear film dehiscence and microaerosol formation. As such, substitution with Tonopen, iCare rebound tonometry or Goldman applanation tonometry should be considered, along with proper instrument sterilization between patients [27]. Specifically, the AAO recommends regular inspection of reusable tonometer tips with a 5-minute soak in 10% bleach solution [28]. Please see the AAO article on How to Disinfect and Calibrate Your Goldmann Applanation Tonometer for more detailed instructions. Providers should also be mindful of other tests, procedures or exam techniques which may increase the risk of transmission and adjust practice accordingly.

Elective Surgery

The AAO, CDC and American College of Surgeons (ACS) recommend that health care providers [23-25]:

- Delay all elective ambulatory provider visits

- Reschedule elective and nonurgent admissions

- Delay inpatient and outpatient elective surgical and procedural cases

- Postpone routine dental and eye care visits

Specifically, the AAO recommends ophthalmologists "cease providing any treatment other than urgent or emergent care immediately" [29]. To help ophthalmologists navigate this shifting surgical landscape and the decision to operate, the AAO has devised a list of common ophthalmologic procedures which may be considered urgent or emergent. This list, made in cooperation with several major subspecialty societies, also covers some of the most common indications for these procedures which may justify more immediate intervention [30].

These measures have been set in place indefinitely, until recommended reinstatement by public health authorities [23]. By following these recommendations, healthcare providers can not only conserve scarce personal protective equipment, but more importantly limit the exposure of COVID-19 to their patients, the health care team and their community.

Urgent/Emergent Surgery

Prior to the surgery, patients should be appropriately screen and tested for COVID-19 if possible and as dictated by their local institution policy. Regarding PPE, N95 respirators and face shields should be considered, especially in cases with aerosol-generating procedures, including intubation. Intubation poses a risk for healthcare providers given the potential for the droplet transmission and aerosolization of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. For a patient with COVID-19 or suspected to have COVID-19, ACS recommends that healthcare workers not needed for intubation should stay outside of the operating room during the procedure. Additionally, a negative pressure operating room should be considered if available. Full ACS recommendations regarding measures to reduce exposures related to surgery are available online [31].

Surgeons and healthcare workers should refer to their local institution policy to ensure adequate protection for patients, co-workers, and themselves.

References

- 1918 Pandemic (H1N1 virus). CDC.gov: US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020. [Last rev. on March 22, 2020; accessed on April 6, 2020 2020] https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html.

- Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). WHO.int: World Health Organization, 2020

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report – 65: World Health Organization, 2020

- Santarpia JL, Rivera DN, Herrera V, Morwitzer MJ, Creager H, Santarpia GW, Crown KK, Brett-Major D, Schnaubelt E, Broadhurst MJ, Lawler JV, Reid SP, Lowe JJ. Transmission Potential of SARS-CoV-2 in Viral Shedding Observed at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. medRxiv 2020;10.1101/2020.03.23.20039446:2020.2003.2023.20039446. DOI: 10.1101/2020.03.23.20039446

- van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, Tamin A, Harcourt JL, Thornburg NJ, Gerber SI, Lloyd-Smith JO, de Wit E, Munster VJ. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. New England Journal of Medicine 2020;10.1056/NEJMc2004973. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973

- Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, Bruce H, Spitters C, Ericson K, Wilkerson S, Tural A, Diaz G, Cohn A, Fox L, Patel A, Gerber SI, Kim L, Tong S, Lu X, Lindstrom S, Pallansch MA, Weldon WC, Biggs HM, Uyeki TM, Pillai SK. First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 2020;382(10):929-936. https://PubMed.gov/32004427. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191

- Lu C-w, Liu X-f, Jia Z-f. 2019-nCoV transmission through the ocular surface must not be ignored. The Lancet 2020;395(10224):e39. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30313-5

- Xia J, Tong J, Liu M, Shen Y, Guo D. Evaluation of coronavirus in tears and conjunctival secretions of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Journal of Medical Virology 2020;n/a(n/a). DOI: 10.1002/jmv.25725

- Yu Jun IS, Anderson DE, Zheng Kang AE, Wang L-F, Rao P, Young BE, Lye DC, Agrawal R. Assessing Viral Shedding and Infectivity of Tears in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Patients. Ophthalmology;10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.03.026. DOI: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.03.026

- Steven S, Yen Ting L, Chonggang X, Ethan R-S, Nick H, Ruian K. High Contagiousness and Rapid Spread of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. Emerging Infectious Disease journal 2020;26(7). DOI: 10.3201/eid2607.200282

- Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, Bretzel G, Froeschl G, Wallrauch C, Zimmer T, Thiel V, Janke C, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Drosten C, Vollmar P, Zwirglmaier K, Zange S, Wölfel R, Hoelscher M. Transmission of 2019-nCoV Infection from an Asymptomatic Contact in Germany. New England Journal of Medicine 2020;382(10):970-971. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468

- Anne Kimball M, Kelly M. Hatfield M, Melissa Arons M, Allison James P, Joanne Taylor P, Kevin Spicer M, Ana C. Bardossy M, Lisa P. Oakley P, Sukarma Tanwar M, Zeshan Chisty M, Jeneita M. Bell M, Mark Methner P, Josh Harney M, Jesica R. Jacobs P, Christina M. Carlson P, Heather P. McLaughlin P, Nimalie Stone M, Clark S, Claire Brostrom-Smith M, Libby C. Page M, Meagan Kay D, James Lewis M, Russell D, Hiatt B, Jessica Gant M, Jeffrey S. Duchin M, Thomas A. Clark M, Margaret A. Honein P, Sujan C. Reddy M, John A. Jernigan M, County PHSK, Team CC-I. Asymptomatic and Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infections in Residents of a Long-Term Care Skilled Nursing Facility — King County, Washington, March 2020. Morbidity and Mortailty Weekly Report (MMWR) 2020;69(13):377-381. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6913e1

- Hu Z, Song C, Xu C, Jin G, Chen Y, Xu X, Ma H, Chen W, Lin Y, Zheng Y, Wang J, Hu Z, Yi Y, Shen H. Clinical characteristics of 24 asymptomatic infections with COVID-19 screened among close contacts in Nanjing, China. Science China Life Sciences 2020;10.1007/s11427-020-1661-4. DOI: 10.1007/s11427-020-1661-4

- Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, Tian F, Jin D-Y, Chen L, Wang M. Presumed Asymptomatic Carrier Transmission of COVID-19. JAMA 2020;10.1001/jama.2020.2565. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565

- Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, Jones FK, Zheng Q, Meredith HR, Azman AS, Reich NG, Lessler J. The Incubation Period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) From Publicly Reported Confirmed Cases: Estimation and Application. Annals of Internal Medicine 2020;10.7326/m20-0504. DOI: 10.7326/m20-0504

- Guan W-j, Ni Z-y, Hu Y, Liang W-h, Ou C-q, He J-x, Liu L, Shan H, Lei C-l, Hui DSC, Du B, Li L-j, Zeng G, Yuen K-Y, Chen R-c, Tang C-l, Wang T, Chen P-y, Xiang J, Li S-y, Wang J-l, Liang Z-j, Peng Y-x, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu Y-h, Peng P, Wang J-m, Liu J-y, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng Z-j, Qiu S-q, Luo J, Ye C-j, Zhu S-y, Zhong N-s. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. New England Journal of Medicine 2020;10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

- Wu P, Duan F, Luo C, Liu Q, Qu X, Liang L, Wu K. Characteristics of Ocular Findings of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Ophthalmology 2020;10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.1291. DOI: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.1291

- Belser JA, Rota PA, Tumpey TM. Ocular tropism of respiratory viruses. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews : MMBR 2013;77(1):144-156. https://PubMed.gov/23471620. DOI: 10.1128/MMBR.00058-12

- Jordan M. Graff M, Hilary Beaver MD. Adenoviral Conjunctivitis: 38-year-old white female with watery, red, irritated eyes; left more than right. EyeRounds.org, 2005. [Last rev. on June 14, 2005; accessed on March 27, 2020 2020] https://eyerounds.org/cases/case28.htm.

- Gautret P, Lagier J-C, Parola P, Hoang VT, Meddeb L, Mailhe M, Doudier B, Courjon J, Giordanengo V, Vieira VE, Dupont HT, Honoré S, Colson P, Chabrière E, La Scola B, Rolain J-M, Brouqui P, Raoult D. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. International journal of antimicrobial agents 2020;10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949:105949-105949. https://PubMed.gov/32205204. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949

- Gao J, Tian Z, Yang X. Breakthrough: Chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. BioScience Trends 2020;14(1):72-73. DOI: 10.5582/bst.2020.01047

- John J. Chen M, PhD, Ryan M. Tarantola M, Christine N. Kay M, Vinit B. Mhajan M, PhD. Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) Toxicity and Recommendations for Screening. EyeRounds.org, 2016. [Last rev. on Spetember 14, 2016; accessed on March 27, 2020 2020] https://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/cases/139-plaquenil-toxicity.htm.

- James Chodosh M, MPH, Gary N. Holland M, Steven Yeh M. Alert: Important coronavirus updates for ophthalmologists. AAO.org: American Academy of Opthalmology, 2020

- Surgeons ACo. COVID-19: Recommendations for Management of Elective Surgical Procedures. FACS.org: American College of Surgeons, 2020

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) - For Healthcare Professionals. CDC.gov: United States Centers for Disease Control, 2020. [Last rev. on April 1, 2020; accessed on April 6, 2020 2020] https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/index.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fhealthcare-facilities%2Findex.html.

- Frequently Asked Questions about Hand Hygiene for Healthcare Personnel Responding to COVID-2019. CDC.gov: Centers for Disease Control, 2020. [Last rev.; accessed on March 26, 2020 2020] https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/infection-control/hcp-hand-hygiene-faq.html.

- Lai THT, Tang EWH, Chau SKY, Fung KSC, Li KKW. Stepping up infection control measures in ophthalmology during the novel coronavirus outbreak: an experience from Hong Kong. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 2020;10.1007/s00417-020-04641-8. DOI: 10.1007/s00417-020-04641-8

- Jennifer Griffin M. How to Disinfect and Calibrate Your Goldmann Applanation Tonometer. EyeNet Magazine: American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2018

- New recommendations for urgent and nonurgent patient care. AAO.org: American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2020. [Last rev. on March 18, 2020; accessed on April 8, 2020 2020] https://www.aao.org/headline/new-recommendations-urgent-nonurgent-patient-care.

- List of urgent and emergent ophthalmic procedures. AAO.org: American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2020. [Last rev. on March 27, 2020; accessed on March 30, 2020 2020] https://www.aao.org/headline/list-of-urgent-emergent-ophthalmic-procedures?fbclid=IwAR0ZgIy1YaVF0BGQ5eS-an5rpSAUCHa77E-b3Usez4V5qZudxojbNUGfYX4.

- COVID-19: Considerations for Optimum Surgeon Protection Before, During, and After Operation. FACS.org: American College of Surgeons, 2020

Suggested Citation Format

Dangremond T, Fox AR, Kemp PS, Oetting TA. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) & Implications for the Eye. EyeRounds.org. Posted April 15, 2020; Available from https://EyeRounds.org/tutorials/coronavirus-disease-eye-implications/index.htm