Orbital Inflammation

Authors: David Ramirez, MD; Smrithi Mani; Erin Shriver, MD, FACS; Scott Vogelgesang, MD

Posted March 28, 2022

Introduction

Orbital inflammation can be attributed to a variety of different etiologies, ranging from various systemic diseases, to metastases of neoplasms, to cancers. In other cases, orbital inflammation can be idiopathic.[1] Further adding to the complexity, conditions causing ocular inflammation may also manifest with orbital inflammation. Systemic diseases that display orbital inflammation include Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (EGPA, formerly called Churg Strauss Syndrome), thyroid eye disease, Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA, formerly called Wegener's Granulomatosis), sarcoidosis, Langerhans's cell histiocytosis, IgG4-related disease, and inflammatory bowel disease (e.g. Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis). Other diseases believed to contribute to orbital inflammation include systemic lupus erythematosus, giant cell arteritis, rheumatoid arthritis, polyarteritis nodosa, scleroderma, and sclerosing cholangitis.[1,2] This article will review the systemic diseases that have been studied in the context of orbital inflammation. Please refer to the specific EyeRounds articles on EGPA and thyroid eye disease for further information regarding orbital involvement.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

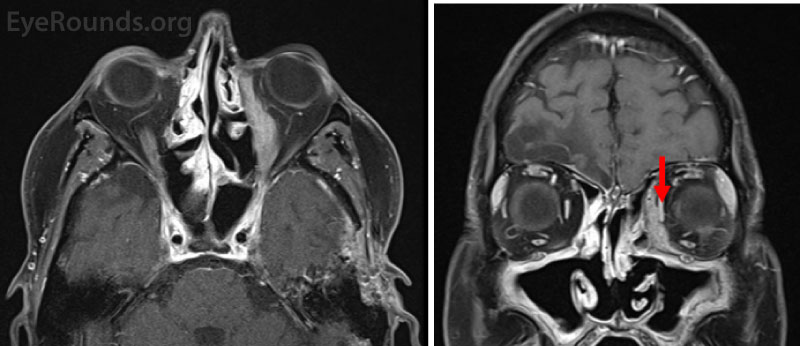

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is a vasculitis characterized by granulomatous inflammation and necrosis. This disease affects 3 in 100,000 people with 40-50% of patients exhibiting orbital symptoms. The pathophysiology of granulomatous with polyangiitis is unknown, but antineutrophil cytoplasmatic antibody (ANCA) is associated with the appearance of GPA and some believe may be pathogenic.[3] In GPA, symptoms vary significantly with no recognizable pattern. Inflammation can present unilaterally or bilaterally and affect any part of the globe (Figure 1). Common symptoms associated with GPA manifested in the orbit include pain, edema and erythema of the eyelid, conjunctival injection, nasolacrimal duct obstruction, epiphora, limited muscle movement, afferent pupillary defect, proptosis, diplopia, and vision loss.[2 ,4]

For a diagnosis of GPA, the ANCA test is typically positive in a cytoplasmic staining pattern (c-ANCA) with concomitant antibodies against proteinase 3 (Pr3). An orbital biopsy would be expected to show granulomatous inflammation with necrosis.[5] Therapy options when GPA involves the pulmonary and renal systems typically include high dose glucocorticoids and either rituximab or cyclophosphamide for induction. More limited disease may be treated with methotrexate, azathioprine, or other disease-modifying anti-rheumatic medications (DMARDs). Maintenance of remission is accomplished with methotrexate, azathioprine, or periodic rituximab.Figure 1: T1-weighted fat-suppressed post-contrast axial (A) and coronal (B) magnetic resonance images (MRI) from a 54-year-old man with a history of recurrent nosebleeds and sinus infections who presented with left-sided proptosis and was diagnosed with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). Both images demonstrate a left-sided enhancing orbital mass between the medial rectus and lamina papyracea. The red arrow marks the normal medial rectus.

Sarcoidosis

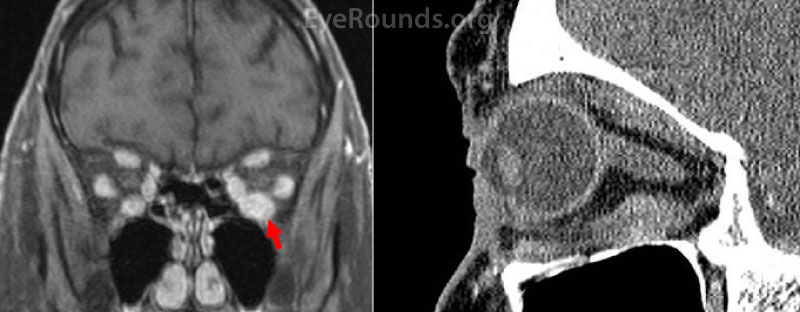

Sarcoidosis (Figure 2) is a non-caseating granulomatous disease that affects multiple body systems. Studies have reported wide estimates of ophthalmic involvement, ranging from 13 to 79%. Females are consistently reported as more likely to develop ophthalmic symptoms.[6-8] The pathophysiology of sarcoidosis is unknown. In orbital sarcoidosis specifically, the lacrimal gland is commonly involved, presenting in 42-63% of patients with sarcoidosis. Other orbital structures affected tend to involve the anterior and inferior orbit.

There are limited studies examining orbital sarcoidosis. In the most recent retrospective study of 26 patients with orbital sarcoidosis, symptoms included (starting with most common): orbital mass/swelling, proptosis, discomfort, ptosis, restricted ocular motility, dry eye, diplopia, and decreased vision.[6 ,7 ,9]

While there are no consensus classification criteria for orbital sarcoidosis specifically, diagnoses are usually reliant on biopsy, with pathology demonstrating non-caseating epithelioid granulomas surrounded by giant cells and lymphocytes. The biopsy findings are often, but not always, accompanied by other clinical and radiologic signs, such as elevated serum angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) or hilar lymphadenopathy on chest x-ray or computed tomography.[6 ,9 ,10]

Given the unknown etiology of sarcoidosis, corticosteroids (oral, topical, or intravitreal) are recommended first line treatment, with the dosage and form of administration at the physician's discretion.[7] Aside from corticosteroids, methotrexate is commonly used. In a retrospective review of 465 sarcoidosis patients with ophthalmic disease, 115 were treated with methotrexate and 101 were treated with methotrexate and prednisone. Both the monotherapy and combined therapy achieved adequate control in the patients, and were both noted to be "efficacious and well tolerated."[11]

Figure 2: T1-weighted fat-suppressed post-contrast MRI coronal section (A) and post-contrast CT sagittal section (B) from a 72-year-old woman presenting with acute vertical binocular diplopia. These images demonstrate enhancement and enlargement of the left inferior rectus muscle without associated fat stranding or osteolysis. This mass was eventually biopsied and demonstrated chronic granulomatous inflammation consistent with sarcoidosis.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

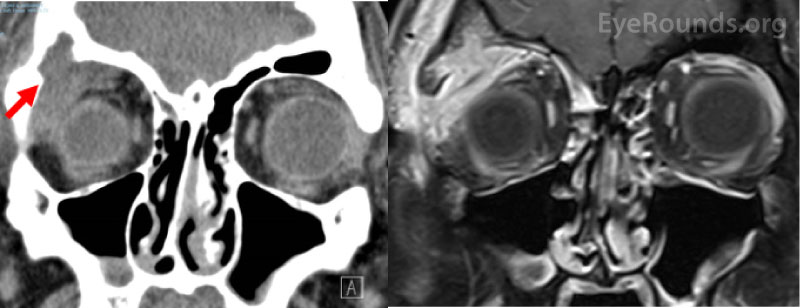

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a disease characterized by the proliferation of Langerhans cells and inflammatory cells (eosinophils in particular). It is typically seen in pediatric patients (specifically ages 1-4) and is more common in males. It can affect single or multiple organ systems. Various prevalence rates of orbital inflammation in LCH have been reported, with one study reporting 37.5%. Orbital involvement in LCH (Figure 3) has been associated with the development of diabetes insipidus in certain patients. The exact pathophysiology of LCH is unknown but is thought to be related to regulatory dysfunction in the immune system.[12]

In the most recent retrospective study of LCH with orbital involvement, the most common symptoms were swelling, proptosis, redness, and pain.[13] Although proptosis is cited as the "telltale" sign of LCH, this study found swelling to be the most common symptom. This study also demonstrated unilateral involvement to be more common than bilateral. [13] In a comprehensive systemic review of LCH, the disease was found predominantly in the superotemporal portion of the orbit, usually presenting as an isolated bone lesion with an associated soft tissue mass.[12]

Tissue biopsy is required for a diagnosis of LCH. Pathology demonstrates proliferation of Langerhans cells, and immunohistochemistry must be positive for S100 and CD1A. Treatment is split between chemotherapy and surgical excision with steroids. For singular focal lesions, surgery is preferred, while for systemic disease chemotherapy is the treatment of choice. Radiation therapy may be used to treat recurrent cases.[12 ,13]

Figure 3: Non-contrast computed tomography coronal section (A) and T1-weighted fat-suppressed post-contrast coronal section (B) from a 26-year-old male patient who presented with several weeks of right upper eyelid swelling and tenderness in the absence of any medical history. Both images show a right superotemporal orbital mass originating from the lacrimal gland with associated bony erosion (arrow). The mass was eventually biopsied and showed eosinophilic granuloma consistent with Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

IgG4-related disease

IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is a slowly evolving systemic disease where IgG4-positive lymphocytes infiltrate single or multiple organs in the body. Common histopathologic features of IgG4-RD include obliterative phlebitis and storiform fibrosis. In addition, there is lymphocytic infiltrate rich in CD4⁺ T cells and IgG4⁺ plasma cells[14]. Often the IgG4⁺:IgG cell ratio is quantified from the biopsy sample, with a ratio greater than 40% indicative of IgG4-RD.[15] Given the variability in IgG4-RD presentation, the American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism defined a specific set of both inclusion and exclusion criteria that must be met to be classified as IgG4-RD, evaluating clinical, serologic, radiologic, and pathologic features in patients. It should be noted that while increased IgG4⁺ plasma cells are found in biopsy samples from organs affected, systemic IgG4 or serum IgG4 elevation is not necessary for diagnosis. Serum IgG4 elevation is highly variable in patients with IgG4-RD.[16]

When IgG4-RD manifests in the orbit, it is known as IgG4-related ophthalmic disease (IgG4-ROD) and is often misdiagnosed as idiopathic orbital inflammation (IOI). In a retrospective study reviewing patients from December 2015-October 2018, 60.6% of patients diagnosed with IOI were actually found to have IgG4-ROD.[17] IgG4-ROD tends to affect adults (mean age of 55.5 years) and both males and females equally.[18] The pathophysiology of IgG4-ROD is unknown, but is thought to be immune-mediated.

IgG4-ROD can present unilaterally or bilaterally and often shows extraocular muscle involvement (45.5% of cases).[14] Multiple retrospective studies of IgG4-ROD also show high rates of lacrimal gland involvement (69-70.3%). In studies reviewing CT and MRI imaging from patients with IgG4-ROD, infraorbital nerve enlargement was a characteristic finding.[19 ,20] The most common symptoms of IgG4-ROD are swelling and proptosis. Other symptoms include eyelid hyperemia, restricted ocular motility, decreased vision, pain, diplopia, and ptosis.[14]

In a systematic review of IgG4-ROD treatment, glucocorticoids were the most common therapy prescribed (dosage was not mentioned in certain studies but assumed to be 0.5-1mg/kg/day of oral prednisone), however 52% of patients on glucocorticoids experienced relapse on cessation or tapering.[21] Rituximab was the most effective biologic used in treating IgG4-ROD, with 93% of patients having a good response. The authors suggested glucocorticoids as the first line therapy and rituximab as second line. [21] There is also evidence that rituximab is effective as a first line monotherapy for IgG4-RD.[22]

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

A systemic review of ophthalmic manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) found orbital inflammation to be present in 0.3-13% of IBD cases.[23] Orbital inflammation is more common in Crohn's disease than in ulcerative colitis. The ophthalmic manifestations of IBD usually present when there is other extra-intestinal involvement. Risk factors for ophthalmic symptoms of IBD include co-existing arthritis and female sex.[23] The pathophysiology of the ophthalmic manifestations of IBD is not well understood; however, one proposed mechanism is gastrointestinal antigen-antibody complex deposition in extra-intestinal tissues. Ophthalmic manifestations usually present during active flares of IBD. In a study of 52 Crohn's patients, 25 patients had ophthalmic symptoms, most commonly reporting redness, pain, decreased vision, and dry eye.[24]

There is no specific testing recommended when ophthalmic symptoms occur in the presence of known IBD. IBD-related orbital inflammation is a diagnosis of exclusion; therefore, it is also important to rule out eye disease secondary to pharmacologic treatment from IBD. To treat orbital inflammation that arises with IBD, systemic treatment is recommended. The treatment of choice is not usually specific to the orbit and aims to control IBD flares. Pharmacologic treatments include mesalamine, sulfasalazine, azathioprine/mercaptopurine, methotrexate and anti-TNF agents such as infliximab and adalimumab. Corticosteroids can also be used to reduce orbital inflammation. [23 ,25]

Idiopathic Orbital Inflammation

This article has covered certain underlying systemic diseases that cause orbital inflammation. However, there are cases in which orbital inflammation is found with no underlying cause. This is referred to as idiopathic orbital inflammation (IOI). The diagnosis of IOI is a diagnosis of exclusion. The pathophysiology, symptoms, and treatment of IOI are complex in nature. For the full-length discussion on IOI, refer to the associated EyeRounds article.

Disease |

General epidemiology and presentation |

Ophthalmic symptoms and features |

Treatment |

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) |

Ages (40-60) |

|

Induction: |

Sarcoidosis |

Ages (50+) |

|

|

Langerhans cell histiocytosis |

Ages (1-4) |

|

|

IgG4-related ophthalmic disease |

Ages (50+) |

|

|

Inflammatory bowel disease |

Any age |

|

|

Table 1: Summary of symptoms and treatment for systemic diseases causing orbital inflammation. Bolded items refer to the more common ophthalmic symptoms and features.

References

- Gordon LK. Orbital inflammatory disease: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Eye (Lond) 2006;20(10):1196-1206. https://PubMed.gov/17019419. DOI: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702383

- Lutt JR, Lim LL, Phal PM, Rosenbaum JT. Orbital inflammatory disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2008;37(4):207-222. https://PubMed.gov/17765951. DOI: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2007.06.003

- Sfiniadaki E, Tsiara I, Theodossiadis P, Chatziralli I. Ocular Manifestations of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis: A Review of the Literature. Ophthalmol Ther 2019;8(2):227-234. https://PubMed.gov/30875067. DOI: 10.1007/s40123-019-0176-8

- Muller K, Lin JH. Orbital granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis): clinical and pathologic findings. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine 2014;138(8):1110-1114. https://PubMed.gov/25076302. DOI: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0006-RS

- Almouhawis HA, Leao JC, Fedele S, Porter SR. Wegener's granulomatosis: a review of clinical features and an update in diagnosis and treatment. J Oral Pathol Med 2013;42(7):507-516. https://PubMed.gov/23301777. DOI: 10.1111/jop.12030

- Pasadhika S, Rosenbaum JT. Ocular Sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med 2015;36(4):669-683. https://PubMed.gov/26593141. DOI: 10.1016/j.ccm.2015.08.009

- Dammacco R, Biswas J, Kivelä TT, Zito FA, Leone P, Mavilio A, Sisto D, Alessio G, Dammacco F. Ocular sarcoidosis: clinical experience and recent pathogenetic and therapeutic advancements. Int Ophthalmol 2020;40(12):3453-3467. https://PubMed.gov/32740881. DOI: 10.1007/s10792-020-01531-0

- Babu K, Smitha KS, F PM. Orbital Sarcoidosis in a High TB Endemic Country - A Case Series from South India. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2020;10.1080/09273948.2019.1707235:1-6. https://PubMed.gov/32073939. DOI: 10.1080/09273948.2019.1707235

- Prabhakaran VC, Saeed P, Esmaeli B, Sullivan TJ, McNab A, Davis G, Valenzuela A, Leibovitch I, Kesler A, Sivak-Callcott J, Hoyama E, Selva D. Orbital and adnexal sarcoidosis. Arch Ophthalmol 2007;125(12):1657-1662. https://PubMed.gov/18071118. DOI: 10.1001/archopht.125.12.1657

- Mochizuki M, Smith JR, Takase H, Kaburaki T, Acharya NR, Rao NA. Revised criteria of International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS) for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis. Br J Ophthalmol 2019;103(10):1418-1422. https://PubMed.gov/30798264. DOI: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313356

- Baughman RP, Lower EE, Ingledue R, Kaufman AH. Management of ocular sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2012;29(1):26-33. https://PubMed.gov/23311120

- Herwig MC, Wojno T, Zhang Q, Grossniklaus HE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the orbit: five clinicopathologic cases and review of the literature. Survey of ophthalmology 2013;58(4):330-340. https://PubMed.gov/23246282. DOI: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.09.004

- Lakatos K, Sterlich K, Pötschger U, Thiem E, Hutter C, Prosch H, Minkov M. Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis of the Orbit: Spectrum of Clinical and Imaging Findings. J Pediatr 2021;230:174-181.e171. https://PubMed.gov/33157073. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.10.056

- Kubota T, Moritani S. Orbital IgG4-Related Disease: Clinical Features and Diagnosis. ISRN rheumatology 2012;2012:412896-412896. https://PubMed.gov/22778989. DOI: 10.5402/2012/412896

- Perugino CA, Stone JH. IgG4-related disease: an update on pathophysiology and implications for clinical care. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2020;16(12):702-714. https://PubMed.gov/32939060. DOI: 10.1038/s41584-020-0500-7

- Wallace ZS, Naden RP, Chari S, Choi HK, Della-Torre E, Dicaire JF, Hart PA, Inoue D, Kawano M, Khosroshahi A, Lanzillotta M, Okazaki K, Perugino CA, Sharma A, Saeki T, Schleinitz N, Takahashi N, Umehara H, Zen Y, Stone JH. The 2019 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for IgG4-related disease. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79(1):77-87. https://PubMed.gov/31796497. DOI: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216561

- Chen J, Zhang P, Ye H, Xiao W, Chen R, Mao Y, Ai S, Liu Z, Tang L, Yang H. Clinical features and outcomes of IgG4-related idiopathic orbital inflammatory disease: from a large southern China-based cohort. Eye (Lond) 2021;35(4):1248-1255. https://PubMed.gov/32661337. DOI: 10.1038/s41433-020-1083-x

- Andrew N, Kearney D, Selva D. IgG4-related orbital disease: a meta-analysis and review. Acta Ophthalmol 2013;91(8):694-700. https://PubMed.gov/22963447. DOI: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2012.02526.x

- Tiegs-Heiden CA, Eckel LJ, Hunt CH, Diehn FE, Schwartz KM, Kallmes DF, Salomão DR, Witzig TE, Garrity JA. Immunoglobulin G4-related disease of the orbit: imaging features in 27 patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35(7):1393-1397. https://PubMed.gov/24627453. DOI: 10.3174/ajnr.A3865

- Yamamoto M, Hashimoto M, Takahashi H, Shinomura Y. IgG4 disease. J Neuroophthalmol 2014;34(4):393-399. https://PubMed.gov/25405661. DOI: 10.1097/wno.0000000000000172

- Detiger SE, Karim AF, Verdijk RM, van Hagen PM, van Laar JAM, Paridaens D. The treatment outcomes in IgG4-related orbital disease: a systematic review of the literature. Acta Ophthalmol 2019;97(5):451-459. https://PubMed.gov/30734497. DOI: 10.1111/aos.14048

- Wallwork R, Wallace Z, Perugino C, Sharma A, Stone JH. Rituximab for idiopathic and IgG4-related retroperitoneal fibrosis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97(42):e12631. https://PubMed.gov/30334947. DOI: 10.1097/md.0000000000012631

- Troncoso LL, Biancardi AL, de Moraes HV, Jr., Zaltman C. Ophthalmic manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A review. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23(32):5836-5848. https://PubMed.gov/28932076. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i32.5836

- Ben Abdesslem N, Mahjoub A, Sayadi S, Zbiba W. Ocular manifestations of crohn's disease. Tunis Med 2019;97(5):692-697. https://PubMed.gov/31729742

- Lee DH, Han JY, Park JJ, Cheon JH, Kim M. Ophthalmologic Manifestation of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review. Korean J Gastroenterol 2019;73(5):269-275. https://PubMed.gov/31132833. DOI: 10.4166/kjg.2019.73.5.269

Suggested Citation Format

Ramirez D, Mani S, Shriver E, Vogelgesang S. Orbital Inflammation. EyeRounds.org. March 28, 2022. Available from https://EyeRounds.org/tutorials/orbital-inflammation/index.htm