Chief Complaint: Blurred vision

History of Present Illness: 12-year-old female with history of newly diagnosed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia who presented with new onset blurry vision with a central scotoma in the left eye for the past two days. She saw her local eye care provider one day prior to presentation and was given the diagnosis of central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR) of the left eye. She had not yet begun chemotherapy or steroids at the time of presentation.

Past Ocular History: None

Past Medical History:

Medications:

Allergies: No known drug allergies

Family History: Paternal Grandmother - Cancer

Social History:

Review of Systems:

OCULAR EXAMINATION

| Right | Left | |

|---|---|---|

| Lids/Lashes | Normal | Normal |

| Conunctiva/Sclera | Trace-1+ injection nasally | Clear and quiet |

| Cornea | 1+ punctate epithelial erosions inferiorly | 1+ punctate epithelial erosions inferiorly |

| Anterior Chamber | Deep and quiet, no cell or flare | Deep and quiet, no cell or flare |

| Iris | Normal architecture | Normal architecture |

| Lens | Clear | Clear |

| Vitreous | Normal, no vitreous cell | Normal, no vitreous cell |

| Right | Left | |

|---|---|---|

| Disc | Normal, no disc edema | Normal, no disc edema |

| C/D Ratio | 0.1 | 0.1 |

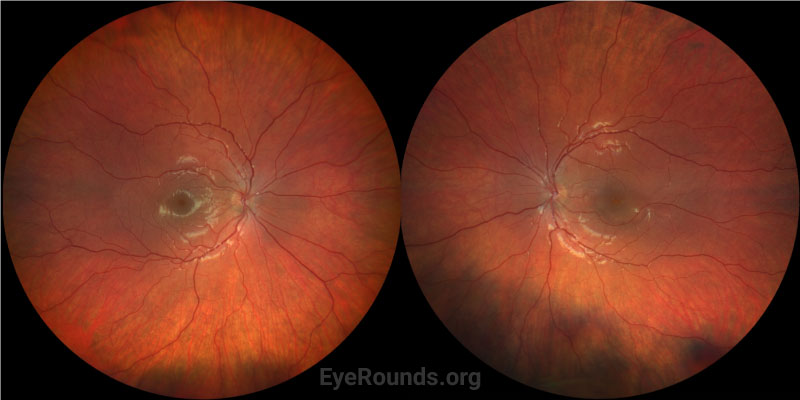

| Macula | Normal | Subretinal fluid with small gutter of fluid inferotemporally, no pigmented epithelial detachment |

| Vessels | Normal | Normal |

| Periphery | Normal, no retinal hemorrhages | Normal, no retinal hemorrhages |

Patient had OCT images and color fundus photos taken on initial presentation. There were additional repeat OCT images taken 2 weeks, 5 weeks, and 3 months after presentation.

Differential Diagnosis

CLINICAL COURSE

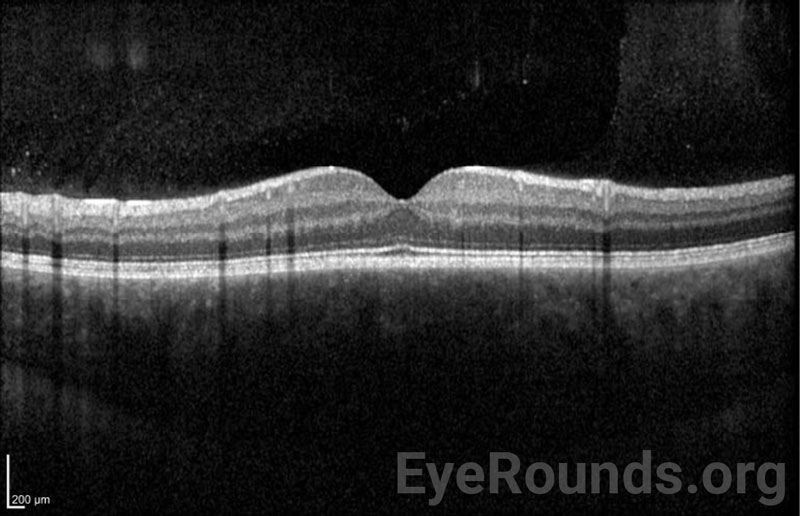

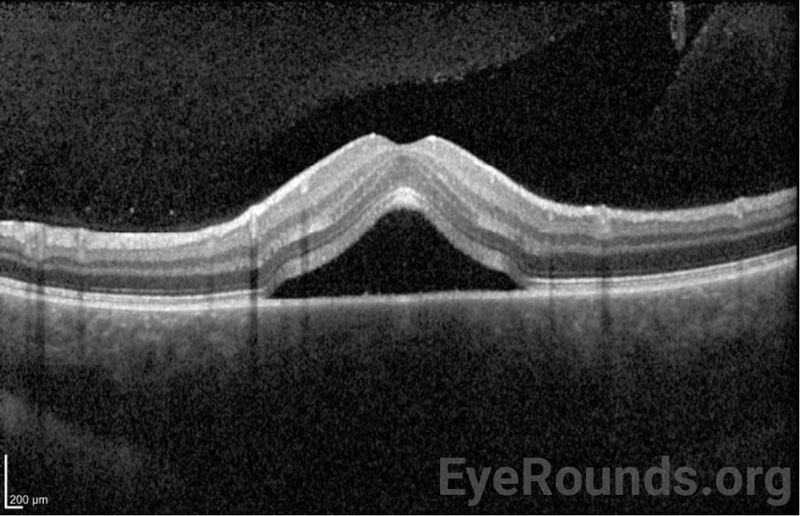

On initial presentation, the patient was diagnosed with a serous macular detachment in the left eye in the setting of bilateral choroidal infiltrates secondary to new diagnosis of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. OCT of the right eye showed normal retinal contour but marked choroidal thickening and congestion. OCT of the left eye showed subfoveal subretinal fluid without a pigment epithelial detachment and choroidal thickening and congestion. Due to the presence of a choroidal infiltrate, she was classified as having central nervous system involvement.[1] She began systemic chemotherapy treatment with cytarabine, vincristine, daunorubicin, pegaspargase, and methotrexate.

At follow-up five weeks later, OCT showed diffuse choroidal thickening that was improved compared to presentation. The serous retinal detachment in the left eye was still present but significantly decreased in size. Her vision was 20/25 with pinhole in both eyes secondary to ocular surface dryness.

At follow up ten weeks after presentation, her vision had improved to 20/20 in both eyes. She remained on the same chemotherapy regimen. OCT of the right eye showed mild, further improved choroidal thickening. OCT of the left eye showed resolved subretinal fluid and continued improvement in choroidal thickening.

At a follow-up appointment three months later, the patient’s OCT of the right and left eyes showed no subretinal fluid with normal choroidal thickness, and her visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes.

At her last oncology follow-up two years after presentation, she remained asymptomatic without recurrence.

DIAGNOSIS: Serous macular detachment with associated choroidal infiltrate secondary to B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia

DISCUSSION

The ocular manifestations of malignant neoplasms of hematopoietic stems cells, such as leukemia, most commonly involve the choroid or retina. In fact, before bone marrow biopsy became the standard of care, ophthalmologists were often consulted to assist with the diagnosis of leukemia as leukemic retinopathy was often present although frequently asymptomatic.[2]

Epidemiology

The eye is involved far more frequently in acute leukemias than in chronic cases.[2] A post-mortem study examining the histopathology of all eyes collected by the Wilmer Eye Institute from 1923 through 1980 found that 80% of patients with all leukemias had ocular involvement (82% in acute leukemia and 75% in chronic leukemia).[2] Clinically, the most often involved tissue is the retina. However, histopathologically the choroid shows leukemic infiltration most consistently.[2] Among the various forms of leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has the highest rate of ocular involvement.[2]

Presentation/Signs/Symptoms

The most common ocular manifestations of leukemia are related to small vessel disease and ischemia, ranging from venous dilatation and tortuosity in the early stages, to cotton wool spots, hemorrhages at all levels of the retina including white-centered hemorrhages, and frank proliferative retinopathy.[2, 3] Serous retinal detachments, as seen in this case, are well-documented as a finding in diagnosis of leukemia but are much less common.[4] The choroid often exhibits thickening secondary to leukemic infiltration.

The most common symptom of leukemic ocular involvement is impaired vision.[3] Presentations differ, with some patients experiencing acute vision loss while others experience blurred vision, scotomas, or metamorphopsia.[5] Patients with serous macular detachment have been reported to experience all of the above symptoms, though blurred vision and metamorphopsia are the most common. Up to 20% of patients have been found to be asymptomatic.[3]

Pathophysiology

The choroid is a sanctuary for leukemic cells due to its high blood flow rate and oxygen availability.[5] In leukemia, the thickening of the choroid is thought to be secondary to perivascular infiltration of neoplastic cells; blast cells have been identified within the choroidal vessels.[4, 6] This leukemic infiltration can result in external compression or internal stagnation of blood leading to choroidal ischemia. Serous macular detachment can occur when the tight junctions within the retinal pigment epithelium are disrupted by ischemia, leading to incompetence of the outer blood retinal barrier, decreased active fluid transport out of the retina, and accumulation of choroidal fluid in the subretinal space.[3, 4] Specific manifestations of leukemic retinopathy seen on fundus exam include cotton-wool spots, intraretinal hemorrhages, and white-centered hemorrhages.[7] It is important to look for optic disc infiltration as it can have a significant impact on vision.[8] Other sequelae of leukemia, including anemia, thrombocytopenia, hyperviscosity, and opportunistic infections, can contribute to the observed retinal findings in leukemic retinopathy.[3]

CSCR is a common mimicker of leukemic choroidal infiltrate due to the shared features of subretinal fluid and choroidal thickening. This is especially true since a major risk factor for CSCR is steroid use, which are commonly prescribed as part of a chemotherapy regimen for leukemias. CSCR on OCT can show dome-shaped serous retinal or RPE detachments, in addition to subretinal fluid.[9] Fluorescein angiography (FA) in CSCR typically shows an expanding area of leakage in the RPE, which is present in about 95% of CSCR cases.[9] Since serous macular detachment due to choroidal infiltration and CSCR have the potential to mimic each other on exam, it is important to consider the context of a patient’s medical history, including a careful history of leukemia and steroid use.[3]

Testing and Laboratory Work-up

OCT and fundus imaging can aid in diagnosis. Initial CBC with differential is imperative if the patient has no previous diagnosis of leukemia. Since ocular findings can be a sign of relapse of leukemia, further laboratory evaluation for systemic recurrence is warranted if they develop after remission.[3]

Treatment

Therapy involves treating the underlying leukemia, typically with systemic chemotherapy.[3, 10] If systemic chemotherapy fails to resolve choroidal or optic nerve infiltration, ocular external beam radiation can be used.[3] Serial OCT imaging is used to monitor progression of choroidal thickening.

Prognosis

In one review of 26 patients with acute leukemia, all patients showed resolution of their serous retinal detachment with treatment of their underlying leukemia. Further, 90% of cases with choroidal thickening showed improvement after systemic leukemia treatment.[5]

SUMMARY

In patients with leukemia, serous macular detachment with associated choroidal infiltrate is a rare, but well-documented ocular finding that can be asymptomatic initially or present as metamorphopsia or loss of visual acuity. Ocular findings may be the initial presentation of leukemia or a sign of disease relapse. The mainstay of treatment is systemic chemotherapy. Systemic therapy often resolves the intraocular pathology and visual symptoms. OCT imaging is helpful in monitoring disease progression and response to treatment.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OR ETIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

*Seen in leukemic retinopathy |

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

|

Kingsbury KD, Hendricks TM, Binkley EM, De Andrade LM. B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with associated choroidal infiltrate and serous macular detachment. EyeRounds.org. Posted August 7, 2023; Available from https://EyeRounds.org/cases/340-B-cell-acute-lymphoblastic-leukemia.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.