Chief Complaint: Progressive vision loss in the left eye

History of Present Illness: A 68-year-old man presented to the emergency department at the University of Iowa with two weeks of progressive vision loss in the left eye. He had been seen by an outside clinician several weeks prior with concern for a branch retinal vein occlusion. At the time of presentation, he reported “looking through a fog” in the left eye. The right eye was asymptomatic.

In addition to his ocular symptoms, the patient was being evaluated for a new skin rash involving the palms of his hands (Figure 1), feet, and genitalia. The rash was characterized as rough, varying in color from white-to-brown, nummular in shape, tender, and non-pruritic. The patient otherwise denied fever, weight loss, shortness of breath, chest pain, or neurologic symptoms such as headache, weakness, and ataxia.

Past Ocular History

Past Medical History

Medications

Allergies

Family History

Social History

Review of Systems

OCULAR EXAMINATION

| Right eye | Left eye | |

|---|---|---|

| Lids/Lashes | Normal | Normal |

| Conunctiva/Sclera | Clear and quiet | Clear and quiet |

| Cornea | Clear | Clear |

| Anterior Chamber | Deep and quiet | Deep and quiet |

| Iris | Normal architecture | Normal architecture |

| Lens | 1+ nucleus sclerosis | 1+ nuclear sclerosis |

| Vitreous | Normal, no cell | Normal, no cell |

| Right eye | Left eye | |

|---|---|---|

| Disc | Normal, no edema or pallor | Trace blurring of the temporal disc margin |

| Cup-to-disc ratio | 0.30 | 0.30 |

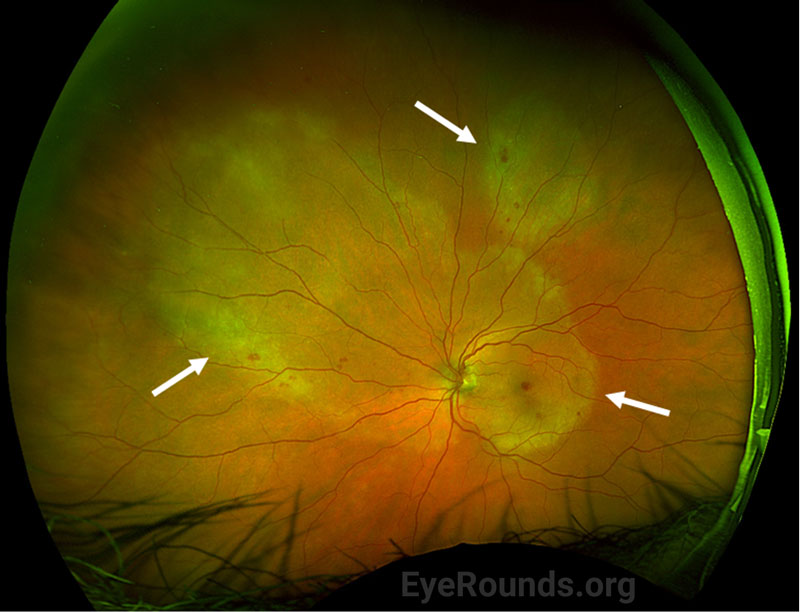

| Macula | Few small hard drusen, no retinal whitening | Confluent placoid regions of retinal opacification throughout the macula with a few intra-retinal hemorrhages |

| Vessels | Normal, no retinal vasculitis | Normal, no retinal vasculitis |

| Periphery | Normal, no retinal whitening | Placoid regions of retinal opacification that extend into the nasal mid-periphery and a second area of opacification superior to the superotemporal arcade |

Differential Diagnosis

CLINICAL COURSE

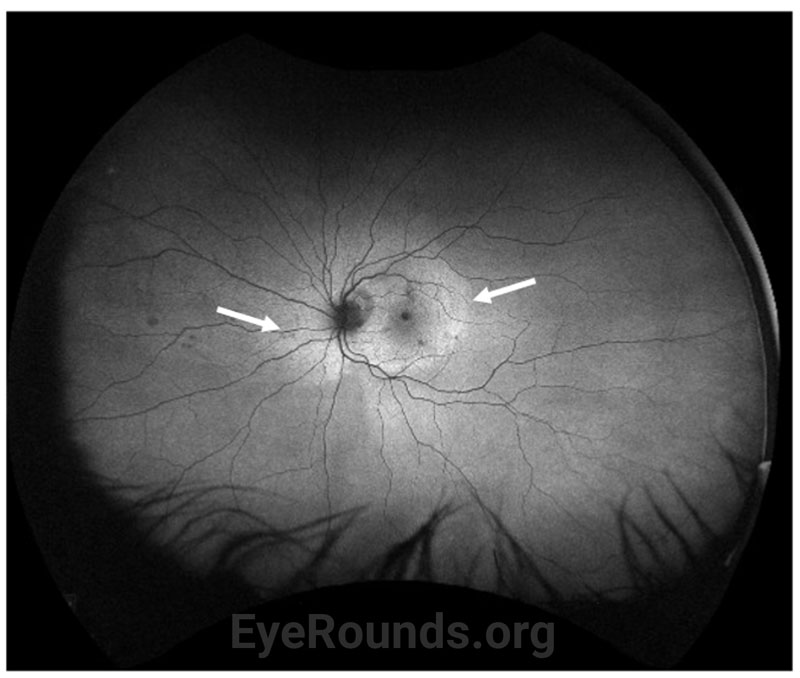

Due to the presence of diffuse placoid retinal opacification in the left eye on presentation (Figure 2), the patient underwent systemic infectious and inflammatory work up as noted above. Syphilitic testing returned positive with a reactive RPR of 1:1024 and positive total syphilis antibody. There was an elevated ESR of 26 mm/Hr and CRP of 10.3 mg/dL, and HIV testing was negative. Continuous IV penicillin 24,000,000 unit infusion over 24 hours for 14 days was initiated per Infectious Disease service recommendations. The patient also underwent an evaluation by the Neurology service for neurosyphilis. MRI of the brain and orbit were unremarkable.

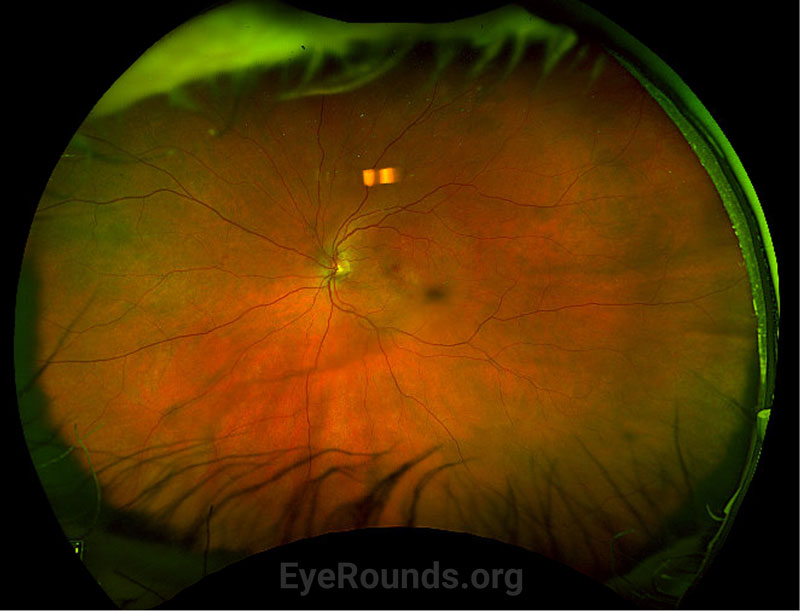

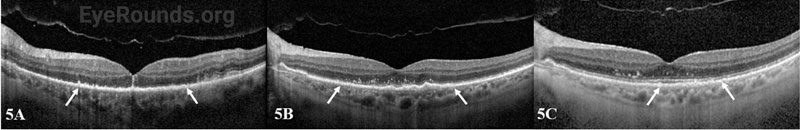

At one-week follow-up, the patient had improvement of his visual acuity to 20/400. Exam demonstrated interval improvement of the confluent areas of placoid whitening. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the left eye demonstrated early reconstitution of the outer retina and improvement of the subretinal hyper-reflective material. At 3-week follow-up, visual acuity improved to 20/50 with near resolution of the previously seen placoid whitening (Figure 4). There was residual outer retinal atrophy seen on OCT with early signs of reconstitution of outer retinal laminations (Figure 5B).

At the 4-month follow-up clinic visit, the patient had further improvement of his visual acuity to 20/25, near complete resolution of the placoid whitening (Figure 6), and continued improvement in reconstitution of the outer retinal layers (Figure 5C).

DIAGNOSIS: Acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis (ASPPC)

DISCUSSION

For the purposes of this discussion, the educational focus will pertain to acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis (ASPPC). For more on other clinical manifestations of ocular syphilis, click here.

Etiology/Epidemiology

In 1990 there were 20.3 cases of syphilis per 100,000 people, which decreased to 2.1 cases per 100,000 people in 2000 as the Centers for Disease Control increased their efforts to eradicate the disease. There has been a rise in syphilis cases in more recent years, and since 2010 the prevalence has doubled [1].

ASPPC is a rare manifestation of ocular syphilis caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. When first described by Gass, it was thought that this clinical phenomenon was predominantly found in immunocompromised patients [2], though current case reports have since demonstrated ASPPC in immunocompetent individuals [3]. Regardless, it is still common practice to test patients for HIV or to investigate other means of immunosuppression, such as chronic steroid use, chemotherapy, and diabetes mellitus [4]. ASPPC occurs bilaterally or unilaterally in even rates, though occurs more often in men compared to women (87% vs 13%) [4].

Pathophysiology

ASPPC was thought by Gass to be due to the widespread dissemination of spirochetes in secondary syphilis causing inflammation near the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). This inflammation near the RPE gives rise to the classic yellow, multifocal, placoid lesions within the macula and peripapillary regions [2]. Others have suggested that this appearance is due to immune complex mediated hypersensitivity[5]. Additional theories include choroidal vessel thrombosis and subsequent dysfunction of the RPE/outer retina due to anti-beta 2 glycoprotein antibodies, which have been shown to be elevated in patients with ASPPC [6]. In reality, the pathogenesis of ASPPC is likely a combination of the two aforementioned infectious and inflammatory pathways that contribute to a common clinical phenotype [7].

Signs/Symptoms

Common presenting symptoms include pain, redness, blurred vision, scotoma, loss of vision, distorted vision, and/or floaters. Classic exam signs include yellowish-white placoid geographic lesions involving the posterior pole [8]. The placoid lesion has a ground-glass appearance that can be distinguished from the whitish necrotic lesions seen in toxoplasma and herpetic eye disease [1]. Retinal lesions are often accompanied by a range of vitritis, and there may be disc edema, serous retinal detachment, retinal hemorrhages, retinal vasculitis, or cystoid macular edema [9].

Testing/Laboratory work-up

Serologic testing for syphilis includes both non-treponemal and treponemal testing. Treponemal testing detects antibodies formed against Treponema pallidum proteins. The main treponemal tests available in the United States include the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test (FTA-ABS), microhemagglutination assay for T. pallidum (MHA-TP), and the T. pallidum enzyme immunoassay (TP-EIA) [10]. In the Unites States, a reactive treponemal test indicates infection with T. pallidum but cannot discern whether the infection is current or resolved, as the antibody remains detectable for life regardless of prior treatment.

Non-treponemal tests detect antibodies formed against decimated host cells, lipid-based antigens, and treponemes. The main non-treponemal tests in the United States include RPR, VDRL, and the toluidine red unheated serum test. These tests indicate the severity of infection and treponemal activity based on titer quantification [11]. The non-treponemal tests are less sensitive and less specific, as they become negative after appropriate treatment. Patients should also be tested for HIV and neurosyphilis should be ruled out with VDRL levels measured from the CSF via lumbar puncture [12].

Imaging

OCT, FAF, indocyanine green angiography (ICGA), fundus photography, fluorescein angiography (FA), and swept source OCT angiography (ss-OCTA) have all been utilized to characterize ASPPC. Below are classical manifestations of ASPPC using these imaging modalities.

Treatment/Management/Guidelines

Co-management with Infectious Disease is recommended. While several case reports have noted spontaneous recovery before treatment [16], general recommendations to optimize overall prognosis and prevent future recurrence include treatment with 10–14 days of IV penicillin [7]. Therefore, the treatment for ocular syphilis is identical to that of neurosyphilis [1].

For patients with primary, secondary, and early stage latent syphilis, the treatment of choice is IM penicillin benzathine G at a dose of 2.4 MU [1]. For patients with a penicillin allergy, desensitization should be considered [17]. If alternative agents must be used, treatment of choice is oral doxycycline at 200 mg for 14 days [1].

In addition, for patients with late-stage latent syphilis, gummatous syphilis, and syphilis affecting the cardiovascular system, the treatment of choice is IM penicillin benzathine G at a dose of 2.4 MU given at 1 week, 8 weeks, and 15 weeks [1]. For patients with a penicillin allergy, treatment of choice is oral doxycycline 200 mg for 21 to 28 days [1].

Sexual contacts should be managed per guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OR ETIOLOGY

|

DIAGNOSIS

|

SYMPTOMS/SIGNS

|

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

|

RELATED CASE: Ocular Syphilis Presenting with Posterior Subcapsular Cataract and Optic Disc Edema

Lee G, Ahmed SB, Mansoor M, Binkley EM. Acute Syphilitic Posterior Placoid Chorioretinitis. EyeRounds.org. Posted August 31, 2023; Available from https://EyeRounds.org/cases/346-ASPPC.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.