New flashing lights and floating "spots."

A 60 year-old female presented to the eye clinic with flashing lights and new floaters in the left eye for the past four days. The floaters were described as "large and stringy", and the flashing lights occurred in the temporal periphery "like a camera flash going off repeatedly". The flashes of light were also worse in a dimly lit environment. She denied any "shades" or "curtains" in her peripheral vision. She denied any recent head trauma or falls. She had no known personal or family history of retinal tears or detachment, and she had no complaints in her right eye. She had no other complaints at presentation.

Eye Drops: None

Past Medical History: Unremarkable

Medications: None

Allergies: No known drug allergies

Family History: No known eye disease

Visual Acuity (Snellen) at distance with correction:

Ocular motility: Full both eyes (OU)

Intraocular Pressure (IOP), via Tonopen: 21 mm Hg OD, 20 mm Hg OS

Pupils: Equally reactive in each eye from 4 mm in the dark to 2 mm in the light. No relative afferent pupillary defect in either eye.

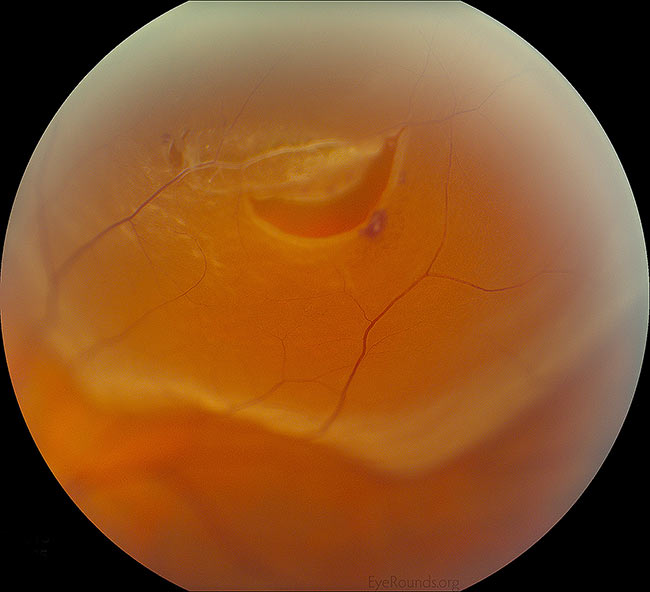

Figure 1: White arrows demonstrate a positive Shafer's sign in a different patient. This patient had strands of vitreous syneresis, which are seen as wispy material just below the white arrows. Our patient did not have Shafer's sign. (Click image for higher resolution)

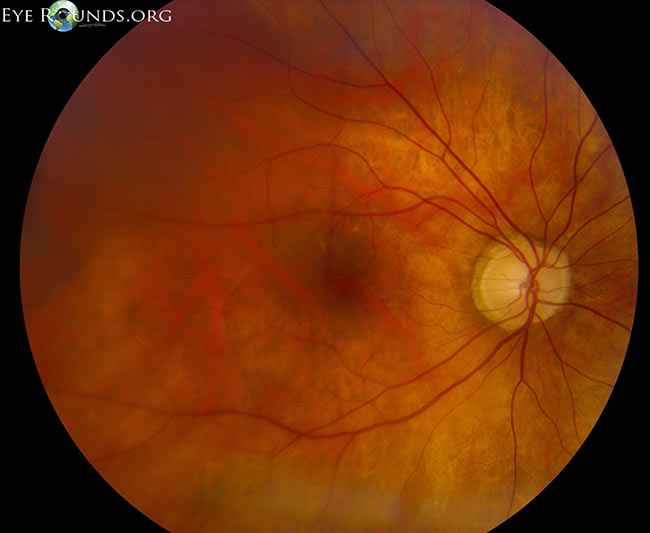

Figure 2: Example of a Weiss ring, indicating detachment of the vitreous from the optic nerve. The optic nerve, retina, and retinal vessels are purposely out of focus because the Weiss ring is located more anteriorly in the vitreous. Credit: PVD Eye Rounds by Matt Weed, MD. (Click image for higher resolution)

The patient had no evidence of a retinal tear or detachment in either eye on 360 degree scleral depressed examination. There was suggestion of an evolving posterior vitreous detachment based on the vitreous syneresis seen in the anterior vitreous and symptoms consistent with separation of the vitreous from the retina. The patient was instructed to monitor her symptoms closely. She was instructed to specifically watch for an increase in amount of severity of her flashes and floaters, or the development of new "curtains" in the periphery of her vision. Follow-up was scheduled for one month for repeat scleral depressed examination in both eyes, sooner if needed.

A posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) is defined as the separation of the posterior hyaloid face from the neurosensory retina. At birth, the vitreous "gel" fills the back of the eye and normally has Jello-like consistency. As one ages, the vitreous undergoes "syneresis," in which it becomes more fluid or liquid-like. The pockets of fluid in the vitreous cavity give the patient a sensation of "floaters" or "cobwebs." As the pockets of fluid collapse on themselves, they gently pull on the retina giving the patient a sensation of "flashes of light" or photopsias. Eventually, the vitreous may completely separate from the neurosensory retina, which is called a posterior vitreous detachment or "PVD" that is confirmed clinically with observation of Weiss ring on funduscopic examination. This usually occurs in one eye at a time, but a PVD in the contralateral eye often occur 6 to 24 months later (6). In high myopia, PVD develops increasingly with age and the degree of myopia (7). As the vitreous gel separates, it may cause a tear in the neurosensory retina which is fragile and thin like a piece of tissue paper. A retinal tear can allow the liquid part of the vitreous to escape behind the retina and separate the retina from its underlying attachments (and blood supply). This is known as a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Typically, however, the vitreous separates without any ill effects on the retina.

Patients are at greatest risk for a symptomatic PVD in the 5th to 7th decade of life, although it can occur much earlier. Most often patients are myopic (near-sighted). High myopes (i.e. refraction of -6.00 or greater) are at increased risk of complications related to a PVD due to thinning of the retina as it is stretched along a longer eye. Other predisposing risk factors for a PVD include a family history of retinal tears or detachments, intraocular inflammation (uveitis), trauma, and previous eye surgery.

The patient in this case exhibited the typical signs and symptoms of an acutely evolving posterior vitreous detachment, including new onset of flashes and floaters. The flashes of light (or photopsias) are often described as a camera flash going off repeatedly in the patient's peripheral vision. The photopsias tend to be more noticeable in dimly lit environments. They are caused by mechanical traction on the retina, caused by the vitreous gel "tugging" on the underlying neurosensory retina.

Patients may also endorse new floaters. Generally these are described by patients as large, wispy objects moving around when they move their eye in different directions of gaze. Sometimes, they will even describe it as something "running" across their vision, like a small mouse, fly, or cobweb in the central or peripheral vision. These are generally a nuisance to the patient, but benign and require only reassurance when in isolation.

Worrisome signs suggestive of a complication related to a retinal tear or detachment may include many, new, tiny floaters often described as "gnats" or "pepper" in the patient's vision. Often these new floaters are "too many to count." This is a worrisome sign, because this may indicate pigment released from the retina and surrounding structures, or red blood cells from a broken retinal vessel. This may indicate that the part of the retina has been torn or detached. Other worrisome signs include a shade or a curtain of vision, which may indicate a retinal detachment where the neurosensory retina has been detached from its underlying connections.

An acute PVD is most commonly caused by the natural process of vitreous shrinkage and liquefaction over time. As mentioned above, as the gel liquefies, the vitreous body collapses and peels off areas of adhesion to the neurosensory retina. The vitreous is normally most strongly adherent to the vitreous base (peripherally and anteriorly), optic nerve, retinal vessels, and fovea center. Other areas of strong adherence are to retinal scars or lattice degeneration. With an acute PVD, symptoms often develop without warning or inciting event. However, in cases of ocular or head trauma, a "traumatic PVD" may occur.

Generally, an acute PVD develops suddenly, but becomes complete within weeks of onset of symptoms. A PVD is considered "partial" when the vitreous jelly is still attached at the macula/optic nerve head and "complete" once total separation of the jelly from the optic nerve head has occurred. Figure 3 shows a horizontal cross section of the neurosensory retina through the fovea center with partial separation of the vitreous gel from the underlying retina. Notice that it is still attached to the optic nerve (right). Accurate staging of this PVD would require evaluation of the peripheral retina; however, OCT confirms that it is only a partial PVD and a complete Weiss ring is unlikely to be present. When a PVD is "complete," the examiner will classically observe a Weiss ring on exam (Figure 2). A "Weiss ring" is the circular peripapillary attachment that is visible within the vitreous after it has become detached from the optic nerve head.

Figure 3: Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the macula from a patient who had complete separation of the vitreous (arrowhead) from the fovea center. Note that the vitreous is still attached at the optic nerve (right side, large arrow), indicating only a partial PVD has occurred.

(Click image for higher resolution)

PVDs can also be associated with vitreous hemorrhage. The presence of blood in the vitreous cavity can make the patient's vision quite poor, and some patients will describe seeing "tiny red floaters" from the red blood cells. It usually is caused by the tearing of a retinal vessel at the time of the vitreous gel peeling off the retina. Spontaneous vitreous hemorrhage in the setting of an acute PVD strongly suggests there may be a retinal tear or detachment. While the blood will likely clear slowly over time, the clinician should have a high index of suspicion for a retinal tear or detachment. The patient should be followed closely to ensure that this is not the case. B-scan ultrasonography may be necessary to assess for retinal tears and detachments if the vitreous hemorrhage is severe enough to obscure the examiner's view.

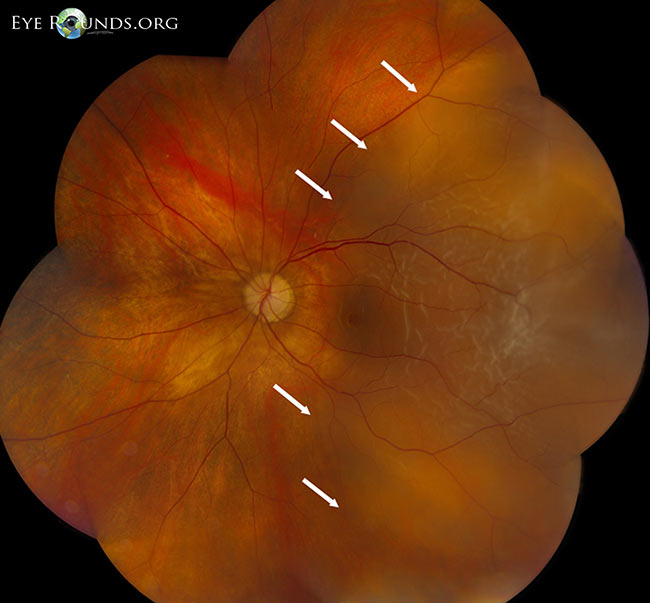

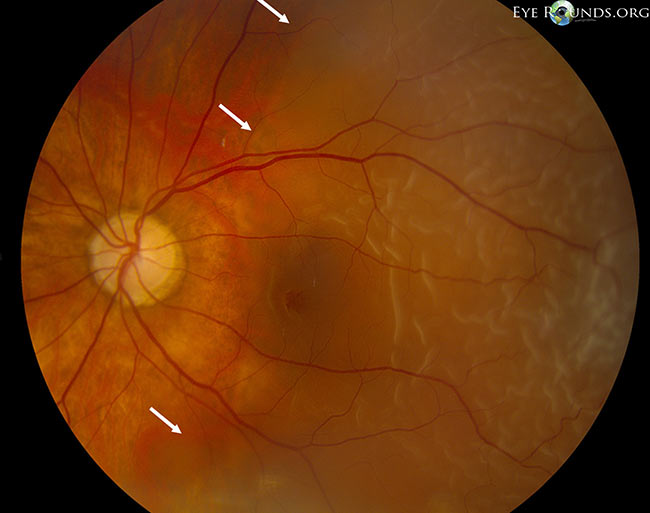

Retinal tears (Figure 4) occur in 10-15% of patients with acute, symptomatic PVDs. For this reason, it is important to have a dilated scleral depressed examination. If a retinal tear occurs, this in and of itself does not have a poor prognosis. Complications arise when the liquefied vitreous escapes through the tear and behind the retina resulting in a neurosensory retinal detachment. If a tear is discovered early, laser demarcation (i.e. "laser barricade" or "laser retinopexy") is a procedure that can be performed in the clinic to prevent progression to a retinal detachment. However, if a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (Figure 5) results, the patient may need to undergo a more involved surgery to reattach the retina. In addition to being a more involved procedure that often warrants going to the operating room, the prognosis may be worse depending on the detachment's severity.

Figure 4: High magnification of a peripheral horseshoe retinal tear adjacent to lattice degeneration, a retinal vessel, and specks of intraretinal hemorrhage. Credit: Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment Eye Rounds by Jesse Vislisel, MD.

(Click image for higher resolution)

|

|

|---|

Figure 5: Low magnification montage, rhegmatogenous macula-off retinal detachment (temporal to the white arrows). Credit: Retinal Detachment Eye Rounds by Eric Chin, MD.

(Click image for higher resolution)

|

|

|

|---|

A hemorrhagic PVD (i.e. vitreous hemorrhage secondary to a PVD) can occur in about 7.5% of PVDs. This occurs when a retinal blood vessel is torn during vitreous separation. The risk of having an underlying retinal tear increases to nearly 70% in the case of a hemorrhagic PVD. Symptoms of a hemorrhagic PVD may include a more significant decrease in vision secondary to the blood dispersed throughout the vitreous cavity.

If one experiences similar symptoms as the patient above (e.g. sudden onset of many new floaters and/or flashes of lights), it is recommended the patient undergo a dilated fundus examination with complete 360 degree scleral depressed examination within 12-24 hours. The examiner should be an eye physician who feels confident in examining the peripheral retina, as this is typically where retinal tears and detachments originate. The examiner will likely examine both eyes thoroughly, even the asymptomatic eye, to ensure no pathology exists. Often times, having a tear in one eye may suggest a predisposition to having additional tears or retinal pathology in the same or contralateral eye. If an isolated retinal tear is found, laser demarcation will likely be advised. If a retinal detachment is present, immediate referral to a retina specialist is warranted.

If an evolving acute PVD is found without any retinal tears or detachments, it is commonly advised to have a follow-up scleral depressed examination approximately one month later. Follow-up varies based on severity, symptoms, and other risk factors. If the PVD is hemorrhagic, or other more concerning signs are present on exam, the examiner may recommend follow-up at more frequent intervals. Although there are no preventative measures, it is generally recommended that the patient avoids heavy exertion, lifting, or bending over in the setting of acute PVD with vitreous hemorrhage so that the blood in the vitreous cavity can settle inferiorly away from the center vision. Elevating the head of the bed will allow gravity to settle the blood inferiorly, out of the visual axis. Patients may continue their blood-thinning medications, as there is no evidence that the discontinuation of antiplatelet or anticoagulant agents speeds the recovery of vitreous hemorrhage.

After the initial examination, the symptoms may persist but hopefully diminish with time. Follow-up at one month is typically adequate barring any new or changing symptoms. Symptoms which would require a more urgent follow-up exam, include many, new, tiny floaters (like "gnats" or "pepper") in the vision, new or increasing frequency of flashes in the vision, or a new shade or curtain of darkness in the visual field.

Acute Posterior Vitreous Detachment (PVD) |

|

Risk factors |

Older age (5th and 7th decades of life) |

Symptoms |

Photopsias (flashes of light), generally unilateral |

Examination |

Dilated fundus exam with 360 degree scleral depression to assess for presence retinal tears or detachments. |

Treatment |

No treatment warranted for an isolated PVD |

Complications |

Vitreous hemorrhage |

Follow up |

Repeat dilated fundus examination within 4-6 weeks for an uncomplicated, non-hemorrhagic PVD, sooner as needed. |

Gauger E, Chin EK, Sohn EH. Vitreous Syneresis: An Impending Posterior Vitreous Detachment (PVD). Oct 16, 2014; Available from: https://eyerounds.org/cases/196-PVD.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.