"Floaters and a shadow in my vision"

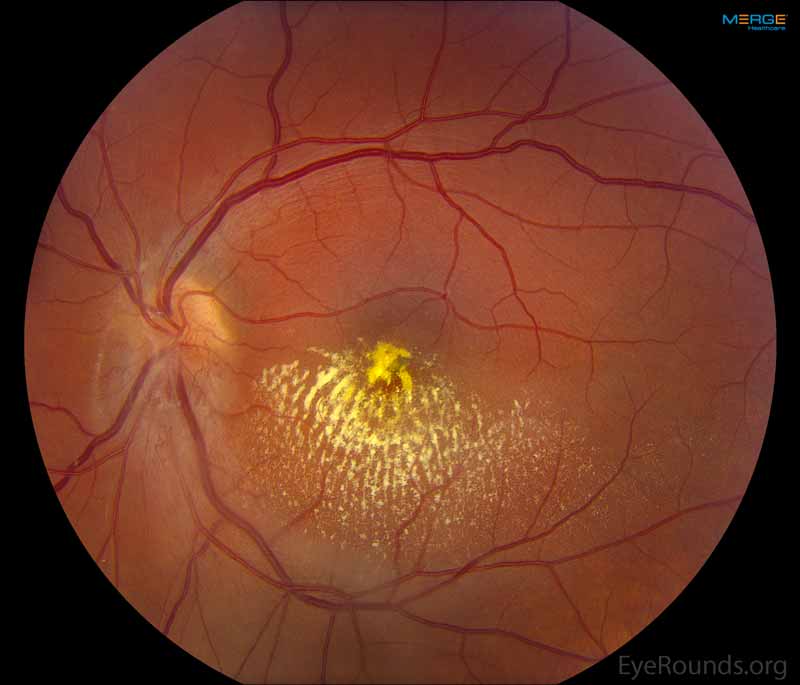

A 19-year-old male presented to his local optometrist with a 4-week history of floaters and a shadow in the superotemporal visual field of his left eye. During this time, he also developed blurring and distortion of his central vision. He denied photopsias or pain. He was asymptomatic in his right eye. The optometrist referred him to a local vitreoretinal surgeon due to concern for a retinal detachment. He was found to have pre-retinal and vitreous hemorrhages in addition to telangiectatic vessels, yellow exudates, and a retinal angioma in the left eye. The patient was then sent to the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics for further evaluation and management.

Figure 1: Right Eye, Color fundus photo from day of presentation. There was a hazy view due to vitreous hemorrhage. There were lipid exudates in the central and inferior macula. There were no light-bulb lesions in the macula.

Figure 2: Right Eye, Wide-field color fundus photo from day of presentation. Telangiectatic vessels with exudates and light bulb lesions were seen at 4:30 in the far periphery.

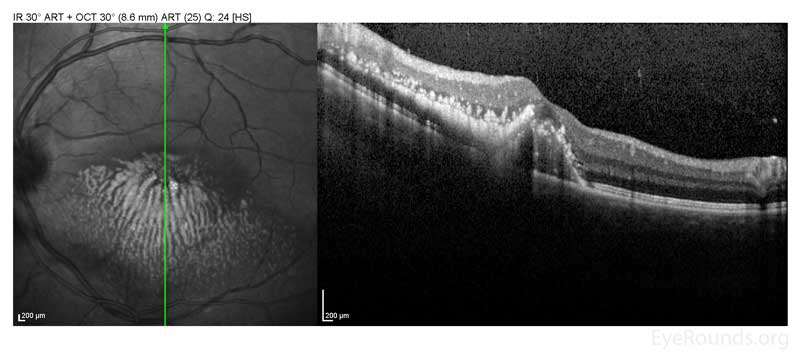

After a funduscopic examination was performed, optical coherence tomography of the macula was obtained which showed a neurosensory retinal detachment of the central and inferior macula with lipid exudates in the left eye (figure 3). Fluorescein angiography showed late hyperfluorescence of the disc and numerous leaking telangiectatic vessels in the left eye (figure 4). Given the patient's age, gender, unilateral findings, and clinical findings of telangiectatic "light bulb" aneurysms, a diagnosis of classical Coats disease was made. B-scan echography was also obtained of the elevated lesion, which was found to be consistent with a vasoproliferative tumor (VPT) (figure 5).

Figure 3: Left Eye, Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the macula. There is a neurosensory detachment of the macula with lipid exudation and vitreous opacities.

Figure 4: Left Eye, B-scan of elevated peripheral VPT. The lesion was found to have medium to high internal reflectivity and measured 1.44 mm (height) by 7.8 mm (base).

Figure 5: Left Eye, Late phase fluorescein angiography (FA) showing disc hyperfluorescence and late leakage of telangiectatic vessels.

The patient elected to proceed with intravitreal injection of bevacizumab that day in clinic. One week later, he underwent focal laser to the retinal telangiectasias inferiorly and to the pseudo-angioma in the left eye. He received several more bevacizumab injections and his vision improved to 20/50 with improvement of his macular edema and lipid exudation (figures 6-7).

Figure 6: Left Eye, Color fundus photo 5 months after presentation following intravitreal bevacizumab and focal laser.

Figure 7: Left Eye, OCT of the macula 5 months after presentation showing improved macular edema after intravitreal bevacizumab.

Coats Disease

Coats disease was first described by Dr. George Coats in 1908.[1] The definition of the disease has since been refined by Reese in 1956 [2] and Shields in 2000.[3] It is characterized by unilateral telangiectatic and aneurysmal retinal vessels with intraretinal fluid, subretinal fluid (SRF), and lipid exudation. It is most commonly found in young males although an adult onset form of the disease has been described.[4] Affected eyes can develop outer retinal thickening and total or partial exudative retinal detachment. The subretinal fluid is viscous and laden with lipid crystals. Retinal capillary dropout is seen distal to the telangiectasias and can lead to neovascularization of the disc with increasing severity of ischemia. The pathology is present in the retinal vasculature, which acquires numerous aneurysms that rarely bleed. Histopathology of the involved vessels reveals a loss of endothelial cells and pericytes along with adventitial thickening.[4] This loss of vascular integrity allows for exudation, resulting in the clinical findings. Research has been undertaken to determine the genetic causes of Coats disease. Several genes such as NDP, CRB1, and PANK2 have been implicated in Coats disease, but none have been definitively related. This has led to the suggestion that a somatic mutation may be the cause.[5]

Coats disease most commonly presents with a chief complaint of decreased visual acuity (43% of cases). Other presenting signs and symptoms include strabismus (23%), leukocoria (20%), pain (3%), heterochromia (1%), and nystagmus (1%). About 8% of cases are detected on routine ocular examination.[6] Initial signs and symptoms of the disease are largely dependent on the age of the patient. Younger children are more likely to present with leukocoria and strabismus, while older children and adults are more likely to detect and report a decrease in visual acuity.[7] The majority of cases present in the first and second decade of life, with the average age of presentation occurring around 5 years old. While it has been clearly shown that younger patients present with higher stages of Coats Disease, no studies to date have linked this to a more rapid progression.[6-9] In fact, it has been shown that age of onset is not directly correlated to poorer visual prognosis.[9] (See below for more discussion on prognosis). Unilateral Coats Disease is most common, and has been reported in >90% of patients in some studies. However, a recent study found subtle peripheral vascular abnormalities in the fellow eye in 22 of 32 patients with unilateral Coats disease.[10] The significance of these findings is unclear.

Visual Acuity: The visual acuity at the time of presentation is highly variable and largely dependent on the extent of disease. Poor vision (≤20/200 VA or comparable) at the time of initial presentation has been shown to occur 44-88% of the time.[6-9]

Anterior Segment: The anterior chamber is normal in about 90% of eyes. However, findings may include cataract (8%), iris neovascularization (4-8%), shallow anterior chamber (4%), cholesterol in the anterior chamber (3%), or megalocornea (2%). Leukocoria has been shown to occur in 20-24% of cases.[6,7]

Dilated Fundus Exam: By definition, all affected eyes will have telangiectasia.[1,2] Other findings include intraretinal exudation (99% of cases), partial exudative retinal detachment (31%), total exudative retinal detachment (47%), retinal hemorrhage (13%), retinal macrocyst (11%), vasoproliferative tumor (6%), optic disc neovascularization (2%), retinal neovascularization (1%), and vitreous hemorrhage.[6]

Currently, no significant correlations have been shown regarding family history, past medical history (including birth and pregnancy history), and systemic signs or symptoms.

It is typically unnecessary to pursue a laboratory evaluation, as Coats disease is primarily a clinical diagnosis.

Numerous imaging modalities have been described and have proven useful in the diagnosis and management of Coats disease. Fluorescein angiography is often quite helpful. This can demonstrate classic findings including telangiectasias and aneurysms, early and progressive vessel leakage, capillary dropout with peripheral areas of non-perfusion, and neovascularization of the disc.[1] Echography can be used to help differentiate lesions from retinoblastoma and can also help to further characterize the type of retinal detachment.[1] Optical coherence tomography can show exudation and neurosensory detachment of the retina. Fine needle aspiration is not recommended and is contraindicated in the presence of total RD or retinoblastoma.

In their review of Coats disease, Ghorbanian and Jaulim explained the usefulness of other imaging modalities such as CT and MRI. When trying to differentiate between advanced Coats disease and retinoblastoma, MRI is superior as it allows for clearer differentiation between subretinal exudation and a solid mass.[11] Also, while intraocular calcifications are a manifestation of retinoblastoma, boney formation has also been seen in cases of Coats disease and therefore this finding should not be used as a means of differentiation.[12] The exudates seen in Coats Disease will be hyperintense on both T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRI images.[12]

It is beneficial to classify the severity of the disease, as this will affect further management and prognosis. Shields et al. stratified the disease into 5 main stages with further substaging (Table 1). Their study showed that after appropriate therapy, the final visual acuity was worse than 20/200 in 0% of patients with stage 1 disease, 53% for stage 2, 74% for stage 3, and 100% for stage 4 and 5.[3] This data should be used to guide counseling sessions and help frame patient and family expectations and goals. The main purpose of management is to reduce retinal telangiectasias and eliminate exudation.

Stage |

Clinical Findings |

Stage 1 |

Retinal telangiectasia only |

Stage 2a |

Telangiectasia and extrafoveal exudation |

Stage 2b |

Telangiectasia and foveal exudation |

Stage 3a1 |

Subtotal, extrafoveal, exudative retinal detachment |

Stage 3a2 |

Subtotal, foveal, exudative retinal detachment |

Stave 3b |

Total exudative retinal detachment |

Stage 4 |

Total retinal detachment and glaucoma |

Stage 5 |

Advanced end-stage disease |

Observation: Clinical observation is recommended for stage 1 and stage 5 disease. Shields et al. showed that Stage 1 disease (telangiectasia with no exudation) that is not threatening vision should simply be observed, as progression is not always imminent.[3] Observation has also been utilized in cases where regaining any vision was highly unlikely. In such cases, enucleation was required in ~20% of cases due to painful secondary glaucoma.[3]

Laser photocoagulation: Laser photocoagulation via indirect ophthalmoscopy is the first-line treatment for Coats disease.[13,14] The goal of laser photocoagulation is to cauterize affected retinal vasculature.[15] While direct treatment to the telangiectatic vessels is the primary mechanism, additionally treating the areas surrounding exudation to act as a barrier has also been described.[13] Argon (most common), Diode, and FD-YAG lasers have all been used.[13]

Cryotherapy: Historically, cryotherapy was the first-line treatment for Coats disease.[3] Now, it's use is typically limited as an adjuvant to laser photocoagulation in more advanced cases when exudation is too thick for laser penetration.[13,16] When utilized as a treatment modality, a double freeze-thaw method is generally used.

Vitreoretinal Surgery: In advanced stage disease unable to be managed with laser photocoagulation or cryotherapy, surgery may be necessary. Methods such as vitrectomy, posterior retinotomy, intraocular silicone or gas use, scleral buckling, and newer minimally invasive techniques have all been described.[17]

Triamcinolone: Intravitreal triamcinolone injection has been shown to reduce subretinal fluid and macular exudates in some studies.[16,18-20] This can facilitate future treatment with laser photocoagulation or cryotherapy. However, due to the common side effects of cataract formation and ocular hypertension, its use is limited.[18] The combination of triamcinolone and cryotherapy has been reported to be associated with inoperable rhegmatogenous retinal detachments and proliferative vitreo-retinopathy.[16]

Anti-VEGF agents: VEGF is increased in the aqueous and vitreous humor of patients with Coats disease.[21] Since 2007, there have been numerous case reports of intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents decreasing subretinal fluid.[11,22] Vitreoretinal fibrosis and traction retinal detachments have been reported following anti-VEGF therapy, so some authors have recommended that the use of injection therapy should be limited to more severe cases in which a decrease in subretinal fluid would aid laser or cryotherapy.[23,24] Ruling out retinoblastoma is crucial prior to injection as treatment in such an eye could result in cancer spread. Diffuse unilateral retinoblastoma can present with an exudative retinal detachment without a calcified mass, making this differentiation challenging.

Enucleation: With advances in treatment and methods to rule out retinoblastoma, enucleation is becoming less common. However, it is still utilized in end stage disease in which secondary glaucoma has resulted in a blind, painful eye.

Intraretinal/Subretinal exudation, retinal detachment (typically worse in younger patients), retinal hemorrhage, vitreous hemorrhage, neovascularization of retina and/or disc, neovascular glaucoma, anterior chamber cholesterolosis, cataracts, uveitis, phthisis

The visual prognosis is directly linked to the stage of disease at the time of presentation.[3,9,25] Involvement of the fovea (exudation and/or detachment) and the presence and extent of retinal detachment have been linked to poorer visual prognosis. The key to better prognosis is earlier detection, which yields earlier treatment.

ETIOLOGY/EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

SIGNSSystemic

Gross findings

DFE

FA

|

PRESENTATION

|

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

|

Kramer BA, Ricca AM, Binkley EM, Boldt HC. Coats Disease. EyeRounds.org. June 30, 2016; Available from: https://eyerounds.org/cases/237-Coats-Disease.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.