The University of Iowa

Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences

Conversion to extra-capsular cataract extraction (ECCE) often comes at a difficult time. The lens is about to fall south, the vitreous has prolapsed and the surgeon is stressed. Understanding the steps and process of conversion to ECCE is essential and study before the crisis will help soothe the stress when this inevitable process occurs. We will cover several areas: identifying patients at risk for the need for conversion to ECCE, indications for conversion, conversion from topical to sub-Tenon’s, wound preparation, expressing the lens material, closure of the wound, placement of the IOL, post-operative issues, and a brief section on anterior vitrectomy.

Patients at risk for conversion to ECCE: One of the most important parts of the pre-operative process for cataract patients is to assess the factors increasing surgical difficulty that may lead to conversion to ECCE or otherwise complicate the procedure.You may want to add operative time to your schedule or ask for additional equipment. You may want to change to a superior limbal wound which facilitates conversion to an ECCE rather than a temporal clear corneal incision. You may want to do a retrobulbar block rather than topical anesthesia as the case may last longer or is more likely to become complicated. In some situations, the pre-operative risk factors make you consider inviting someone more experienced to do the case.

| Factor | Time | Equipment/Anesthesia |

|---|---|---|

| Zonular Laxity | Double |

|

| Rock Hard Lens | Add 50% |

|

| Small Pupil | Add 50% |

|

| Flomax | Add 50% |

|

| Poor Red Reflex | Add 50% |

|

| Big Brow | Add 25% |

|

| Narrow Angle | Add 25% |

|

| Predisposition to corneal decompensation | 0% |

|

| Existing Trabeculectomy bleb | 0% |

|

| Prior vitrectomy (PPVx) | 0% |

|

| Cannot lay flat | 0% |

|

| Anticoagulant use | 0% |

|

| Monocular patient | 0% |

|

| (modified from Oetting, Cataract Surgery for Greenhorns, http://medrounds.org/cataract-surgery-greenhorns) | ||

Indications for conversion: Conversion to ECCE is indicated when phacoemulsification is failing. Sometimes this is due to a very hard lens which does not submit to ultrasound or a lens that is hard enough that the surgeon is concerned that the required ultrasound energy will harm a tentative cornea (e.g. Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy or posterior polymorphous dystrophy [PPMD]). Sometimes one will convert to ECCE when an errant capsulorhexis goes radial especially with a hard crystalline lens when the surgeon is concerned that the risk of dropping the lens is too great with continued phacoemulsification. A surgeon may choose to convert to ECCE when the anterior capsule is hard to see and capsulorhexis must be completed with the can opener technique (however, with the use of Trypan Blue stain this is less commonly indicated). More often the conversion is indicated when the crystalline lens is loose from weak zonules or a posterior capsule tear which make phacoemulsification less safe than extending the wound and removing the residual lens material. Indications for conversion to ECCE include:

Converting to sub-Tenon’s anesthesia. Often we convert cases from topical clear corneal to ECCE. While the ECCE can be done under topical it is usually more comfortable and safer to give additional anesthetic which is typically a sub tenon’s injection of bupivicaine and lidocaine. This will provide some akinesia and additional anesthesia. There is usually subconjunctival hemorrhage and if the injection is made too anterior it can cause chemoisis and ballooning of the conjunctiva. The steps of the sub-Tenon’s injection are outlined below:1

Converting the Wound: The major step toward converting to ECCE is to either extend the existing wound or close and make another. The ECCE will require a large incision of from 9-12 mm which is closed with suture. The decision to extend the existing wound or make a new wound hinges on several factors: location of the original wound, size of the brow, past surgical history, and possible need for future surgery.

| Original wound | Advantages of making new wound for ECCE | Advantages of extending existing wound for ECCE |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal |

|

|

| Supero-temporal (Left eye) |

|

|

| Infero-temporal (Right eye) |

|

|

| Superior |

|

|

Making a new incision during conversion is identical to that for a planned ECCE. The original incision is closed with a 10-O nylon suture. The surgeon and microscope are rotated as the surgeon should sit superior. The steps to make a new superior incision are:

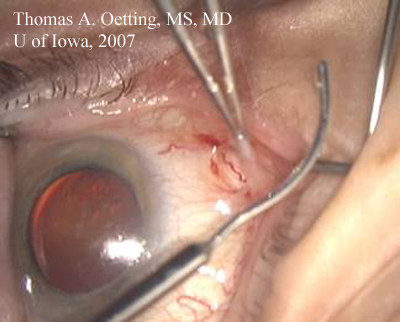

Extending an existing incision can be tricky and the technique is different for scleral tunnels compared to clear corneal incisions. However in both cases the original extension is brought to the limbus. In the case of an original scleral incision the incision is brought anterior to join the limbus on either end before extending along the limbus for a chordlength of about 11mm. In the case of an existing corneal incision the corneal incision is brought posterior toward the limbus before extending the wound along the limbus for a chord length of about 11mm. When iris hooks are being used in a diamond configuration the wound can be extended to preserve the sub-incisional hook and the large pupil.2

Removing the lens: One has to be far more careful when removing the nucleus during the typical conversion to ECCE which comes along with vitreous loss. First the anterior capsule must be large enough to allow the nucleus to express which may require relaxing incisions in some cases. When the zonules are weak or the posterior capsule is torn the lens cannot be expressed with fluid or external pressure as is often done with a planned ECCE with intact capsule/zonlules. After any vitreous is removed (see below), the lens must be carefully looped out of the anterior chamber with minimal pressure on the globe. If the posterior capsule and zonlues are intact then the lens can be expressed as described with a planned ECCE.

Removing lens with intact capsule complex:

Removing lens with vitreous present:

Placement of the IOL: IOL selection with ECCE conversion depends on the residual capsular complex.3,4 The key to IOL centration is to get both of the haptics in the same place: either both in the bag or both in the sulcus.

Post-operative issues: Post-operative care for patients following conversion from phaco to ECCE is a bit more complicated and focuses on preventing cystoid macular edema (CME) and limiting induced astigmatism. Often the care is very similar to that of a planned ECCE with about 3 post-operative visits (one the same or next day, one a week later, and one about 5-6 weeks later). Depending on the amount of astigmatism the patient may require several visits to sequentially remove sutures while eliminating induced astigmatism.

First post-operative visit: This visit is often on the same afternoon (4-6 hours following surgery) or the next morning with the primary emphasis to check the IOP, look for wound leaks, and scan for residual lens material or vitreous in the anterior chamber. Certainly most wound leaks should be sutured, but if the AC is not formed closing these is mandatory. Residual nuclear material should be removed in the next few days if present but residual cortical material will often dissolve away with little inflammation. You would expect poor vision in the 20/200 range due to astigmatism and edema. The anterior chamber should be formed and typically has moderate cell (10-20 cells/hpf with 0.2 mm beam). If the IOP is less than 10 mmHg, search carefully with a high index of suspicion for a leak using Seidel testing. If the IOP is in the 10-29 range, then everything is probably okay unless the patient is a vasculopath, in which case your upper limit of IOP tolerance should be lowered. If the IOP is in the 30-39 range consider aqueous suppression. If the IOP is >40 than consider aqueous suppression and "burping" or "bleeding down" the IOP through the paracentesis or an anterior chamber tap. The IOP should be rechecked 60-90 minutes later to ensure success with your treatment. Look at the fundus to rule out retinal detachment (RD) and choroidal effusion or hemorrhage. Typically patients are placed on prednisolone acetate 1% 1 drop 4 times a day (QID), cyclogyl 1% 1 drop 2 times a day (BID), and an antibiotic 1 drop QID for the next week.

Week 1 post-operative visit: The vision and pressure should dramatically improve in patients over the next week after a case that was converted to ECCE. The vision should be in the 20/100 range with pinhole improvement to around 20/50. The vision is usually limited by residual edema and astigmatism. In a study of our ECCE cases, we found about 7.0 diopters of cylinder at the one week visit. You should expect very little inflammation and document that no RD exists. Search for residual lens material in the anterior segment and posterior pole. You can discontinue the cyclogyl and the antibiotic. Slowly taper the prednisolone acetate (e.g., 1 gtt QID for 7 more days, then 1 gtt three times a day [TID] for 7 days, then 1 gtt BID for 7 days, then 1 gtt QD for 7 days), then discontinue. If the patient is at risk for cystoid macular edema (CME), as is possible with vitreous loss, then you should keep on prednisolone at the higher frequency (e.g., QID) and start a non steroidal (like topical ketorolac or equivalent 1 gtt QID) until the next visit 4 -6 weeks later.

Week 5 post-operative visit: The vision should continue to improve as the astigmatism settles and the cornea clears further. The eye should be comfortable. The vision should be in the 20/80 range, improving to 20/40 with pinhole. In our study the astigmatism induced by ECCE sutures was about 5.0 diopters at the incision. The anterior segment should be quiet and the IOP normal (unless the patient is a "steroid responder"). Consider CME as a possibility in patients where conversion was required as these cases are often long and can involve vitreous loss. Evaluate as clinically indicated by exam or history with optical coherence tomography (OCT) or flourescein angiography (FFA).

By this point in the recovery, the main issue is astigmatic control with suture removal. Use keratometry, refraction, streak retinoscopy, or topography to guide your suture removal. If the keratometry is 45.00 @ 90, and 40.00 @ 180, then look for tight sutures at around 90 degrees (12 o'clock) that are causing 5 diopters of cylinder. You can take only one suture at 5 weeks, but by the 8 week evaluation, you could consider 2 sutures removed at a time. The plan is to remove a suture and see how the cornea settles. When the astigmatism is less than about 1.0 to 1.5 diopters you should stop suture removal and correct any residual astigmatism with refraction. Use antibiotic drops prophylactically for a few days after each suture removal. After this visit you should consider the following choices with each visit (don’t waste too much time thinking about other possibilities and remember not everybody is going to be 20/20):

Anterior Vitrectomy. Converting to ECCE is almost always accompanied by vitreous. Sometimes the conversion comes when the lens is too hard and the capsule is intact but most often it seems conversion comes when the zonules or capsule releases the vitreous into the reluctant hands of the anterior segment surgeon. We will cover the causes and signs of vitreous prolapse and the principals of anterior vitrectomy in various situations.

Causes of vitreous prolapse. The vitreous either comes around the zonules or through a tear in the posterior capsule. Posterior capsular tears are caused commonly by 1) anterior tear extending posteriorly – most common, 2) posterior tear – secondary to phaco needle or chopper being too deep, 3) during manipulation with the I/A instrument, or 4) a pre-existing injury (e.g., posterior polar cataract, iatrogenic from PPVx, or from penetrating lens trauma). Zonular problems are often pre-existing (e.g., from trauma, PXF, or Marfan’s syndrome) but can also be iatrogenic from forceful rotation of the lens or pulling on the capsule during I/A.

Signs of vitreous prolapse. Thefirst sign of vitreous prolapse is denial. Something seems wrong but you can’t quite pin point the issue. At first you deny that an issue exists but soon it becomes clear. More tell-tale signs of vitreous prolapse include 1) deepening of the chamber, 2) widening of the pupil, 3) lens material no longer centered, 4) lens particles no longer come to phaco or I/A, and 5) the lens no longer rotates freely. When you suspect vitreous prolapse you should place dispersive OVD into the eye before removing the phaco needle or I/A and can check the wound with a Weck-Cel (or similar arrow sponge) for vitreous.

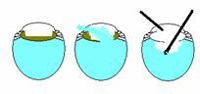

Basic Principles of anterior vitrectomy. The key to a successful anterior vitrectomy is to control the fluidics of the eye. The first step is to close the chamber. This is often hard when you have converted to an ECCE as the wound is large. However you must close the wound so that the only exit point for fluid is the aspiration/cutting device. Separate the irrigation device from the aspiration/cutting device so that you can create a pressure differential such that the vitreous is encouraged to go to the aspiration/cutter. The final important point is to cut low and irrigate high. If you can place the irrigation device in the anterior chamber above the aspiration/cutter down near the plane of the posterior capsule than the vitreous will leave the anterior chamber.

|

|

In general the bottle height should be low – just high enough to keep the AC formed and not so high to push fluid and possibly vitreous out from the eye. The cutting rate should be as high as possible when cutting vitreous and low when cutting cortical lens material. We will separately discuss early-, mid-, and late-case vitreous loss below.

Vitreous Presenting early in case –while most of crystalline lens is in eye: This is the worst time for vitreous to prolapse and one should strongly consider converting to ECCE. The steps to consider are outlined below:1

Staining the Vitreous with Kenalog: Scott Burk at Cincinatti Eye described using Kenalog off-label to stain vitreous that had prolapsed into the anterior chamber5 link to Facebook video. As Kenalog is not approved by the FDA for this indication and as some retnal surgeons have had sterile (and even infectious) endophthalmitis from using Kenalog, its use is controversial. However it is a very useful adjunct to anterior vitrectomy. The method for mixing the triamcinolone (Kenalog) to dilute 10:1 and to wash off the preservative follows: