Ocular Surface Tumors

Matthew Benage, MD; Austin R. Fox, MD; Michelle R. Boyce, MD; Mark A. Greiner, MD

Key contributor: Nasreen A. Syed, MD

Ocular surface tumors are rare but potentially deadly diseases of the conjunctiva and/or cornea. It is important for ophthalmologists to recognize the characteristics of ocular surface tumors and to have an understanding of their management. Below, we will review the diagnosis, pathology, and treatment of the most common ocular surface tumors.

Conjunctival melanomas (CM) comprise approximately 2% of all ocular surface malignancies and 0.25% of all melanomas.[1] Non-Hispanic Caucasians are most commonly affected, with an incidence of 0.2-0.8 per million. Non-whites are rarely affected.[2] Studies have failed to show consistent predilection for sex.[3] The median age of presentation is approximately 60 years.[4] Risk factors have been difficult to ascertain due to the low incidence of disease. However, studies have reported risk for those with fair skin and hair, a family history, certain genetic syndromes (familial melanoma syndromes, xeroderma pigmentosum), and significant ultraviolet (UV) light exposure.[5-7]

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) study reported an increased incidence of conjunctival melanoma in white males. The mechanism is hypothesized to be secondary to increased UV light exposure.[8] There is also a strong association between primary acquired melanosis (PAM) and conjunctival nevi with CM.[4,9] In particular, PAM with severe atypia transforms into CM in 13% of cases, with greater risk associated with more extensive circumferential spread of PAM.[9] PAM without atypia or with mild atypia does not demonstrate a predisposition for progression to melanoma.[9] Conjunctival melanomas arises from three sources: PAM, de novo, and nevus; with PAM being most common and nevus being least common.[4]

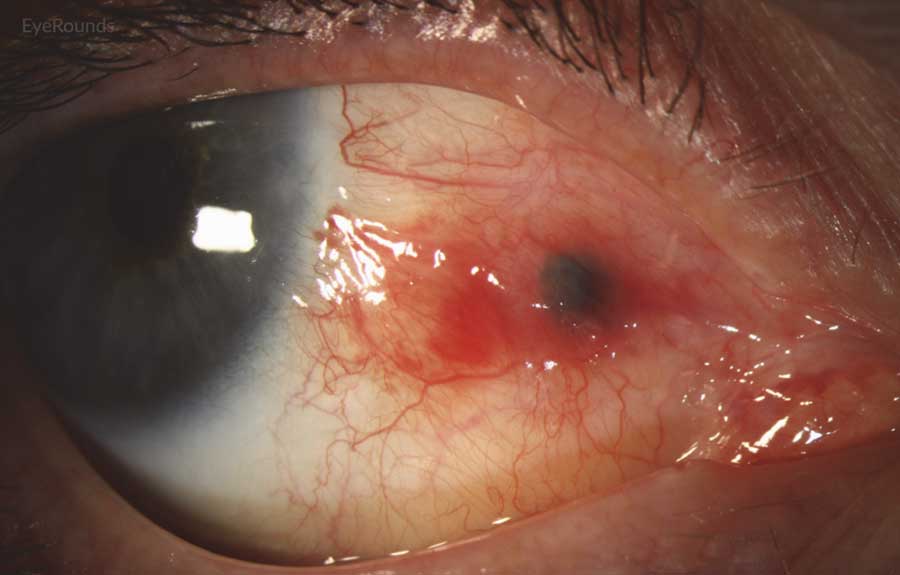

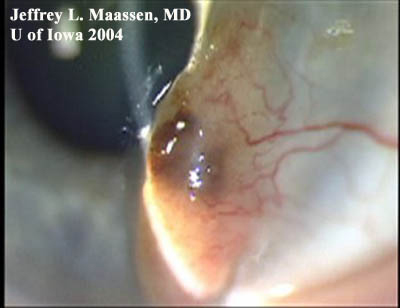

CM commonly presents as a raised, thick, pigmented lesion with surrounding feeder vessels. However, amelanotic lesions occur in approximately 15-20% of cases.[10] CM is typically unilateral and can occur at almost any anatomical location within the conjunctiva, with the most common location being on the bulbar conjunctiva (Figures 1 and 2).[10] Less commonly, CM occurs on the palpebral and forniceal conjunctiva, the plica semilunaris, caruncle, or cornea, with these locations portending a poorer prognosis.[10] Deep extension into the cornea is limited by Bowman's membrane, which acts as a barrier, though it can extend across the corneal epithelium (Figure 3).[1] CM has a propensity to metastasize, most commonly to the preauricular or anterior cervical lymph nodes.

|

|

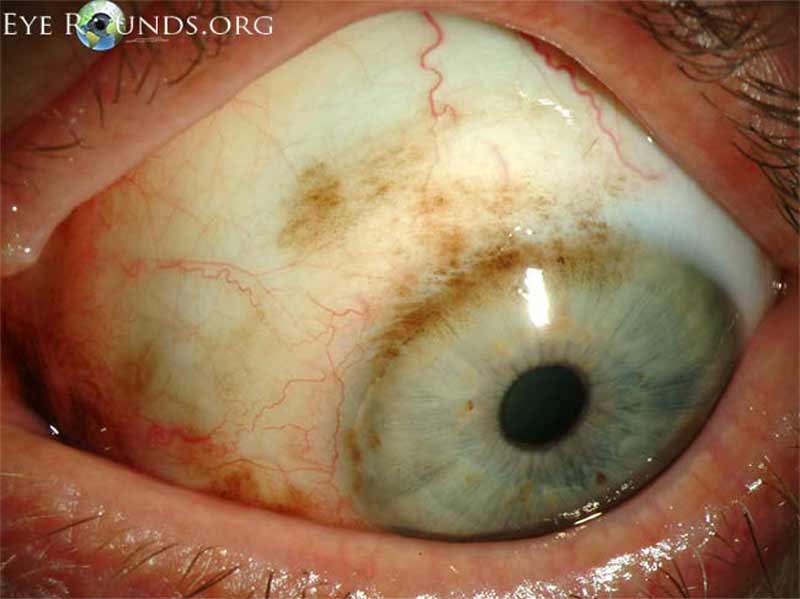

Figure 1: Conjunctival melanoma

Slit lamp photograph demonstrating a slightly elevated pigmented lesion with small feeder vessels. Clinically, there was recent growth noted, initiating biopsy and subsequent diagnosis of conjunctival melanoma

|

|

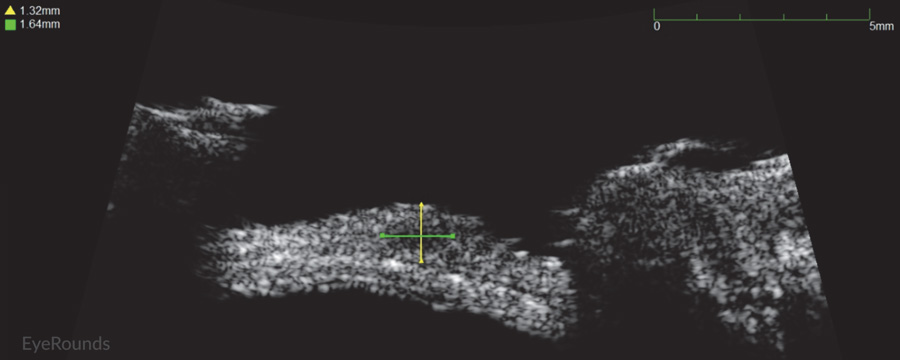

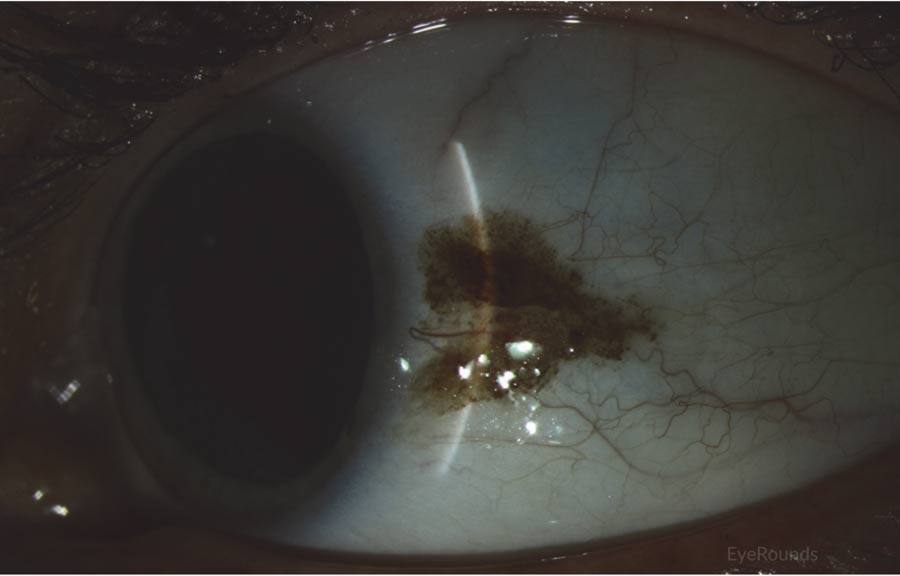

Figure 2: Conjunctival melanoma recurrence

Slit lamp photograph demonstrating recurrence of amelanotic melanoma with underlying scleral degeneration (upper images). High-frequency anterior segment ultrasound displaying elevation of conjunctival lesion without extension into sclera (bottom image).

|

|

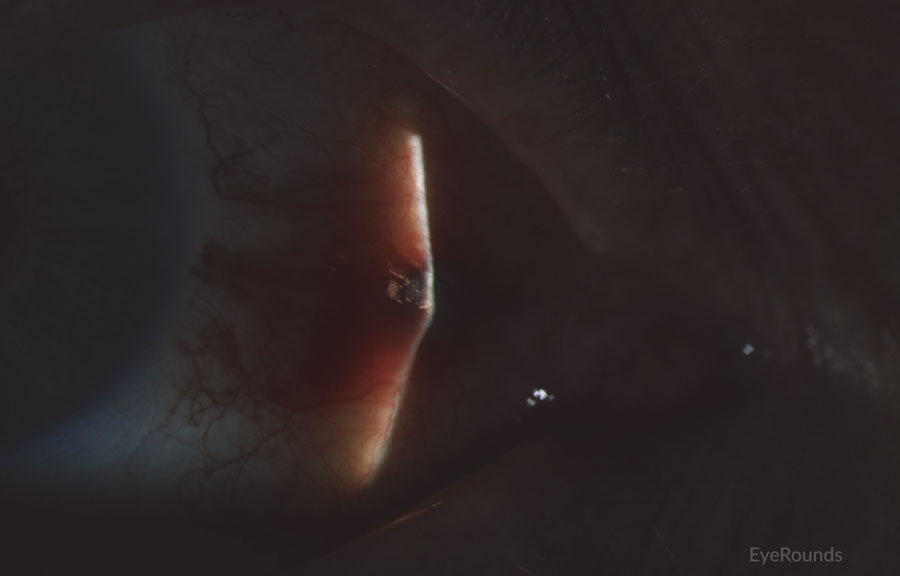

Figure 3: Conjunctival melanoma after resection

Slit lamp photo demonstrating the recurrence of a large raised, pigmented lesion extending onto the cornea with a prominent feeder vessel.

Melanocytic tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea include benign conjunctival nevi, primary acquired melanosis (PAM), as well as the less common, but more dangerous, invasive melanoma. Therefore, an important task is differentiating CM from PAM and conjunctival nevi.

PAM is a common entity, with one study of Caucasians displaying PAM in one-third of patients.[11] PAM typically presents as a unilateral, pigmented, flat, non-cystic lesion on the conjunctiva, often with pigment stippling extending beyond the main concentration of pigmentation (Figure 4). PAM involves the conjunctiva, unlike scleral pigmentation that occurs in ocular melanocytosis. Therefore, the overlying pigmented conjunctiva can be moved with a cotton tip over the underlying sclera.

While no consensus has been established for clinical characteristics that distinguish between benign PAM from premalignant PAM or malignant melanoma, suspicion should be high for lesions that display the following characteristics: extension of pigmentation greater than 3 clock hours of conjunctiva, large, raised, thickened, darkly melanotic, multifocal, or rapidly progressive lesions. In addition, lesions in unusual locations such as the fornix, semilunar fold, caruncle, or palpebral conjunctiva should be viewed with suspicion for malignant potential (Table 1). Importantly, an extension of pigmentation >3 clock hours portends a 20% risk of malignant transformation. Each clock hour increases relative risk of transformation to melanoma by 1.7 times.[9]

Table 1.

| PAM Risk Factors | |

| Higher Risk | Lower Risk |

| >3 clock hours involvement of conjunctiva | Small, circumscribed without extensive involvement of conjunctiva |

| Extension onto cornea | Confinement to the conjunctiva |

| Nodular | Flat |

| Multifocal | One lesion |

| Highly vascular | Minimal vasculature |

| History of skin or conjunctival melanoma | No history of skin or conjunctival melanoma |

| Older age | Young age |

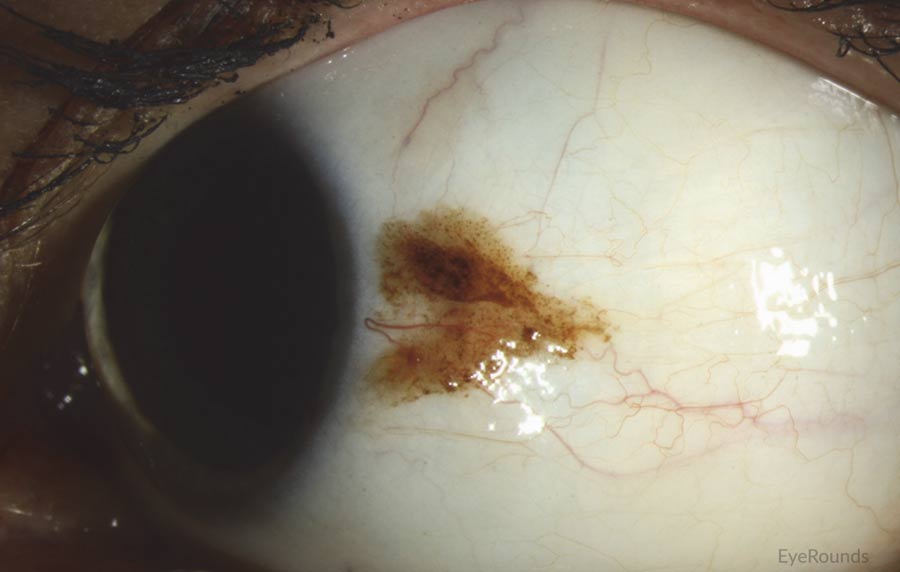

Figure 4: Primary acquired melanosis

Slit lamp photo displaying flat, non-cystic PAM that covers 2.5-3 clock hours of conjunctiva.

Conjunctival nevi typically present as unilateral, pigmented, and oftentimes cystic lesions (figure 5). These lesions are typically located on the limbal or perilimbal conjunctiva in the interpalpebral fissure. An important distinguishing factor from invasive melanoma is the lack of prominent feeder vessels and presence of cysts. It is believed that some conjunctival nevi may rarely undergo malignant transformation.[12]

Figure 5: Conjunctival nevus

Slit lamp photograph displaying a well circumscribed, slightly elevated lesion. Note the small cysts medially.

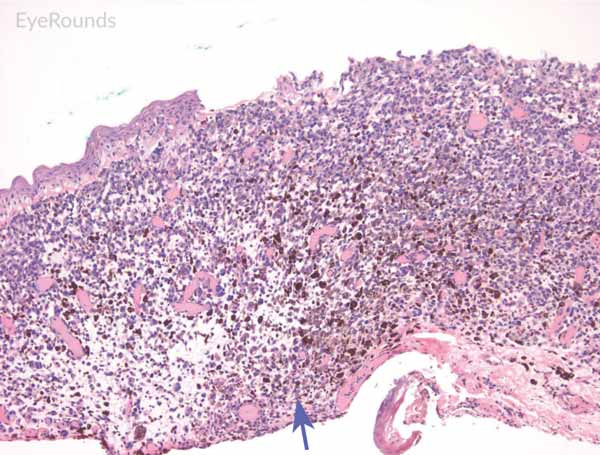

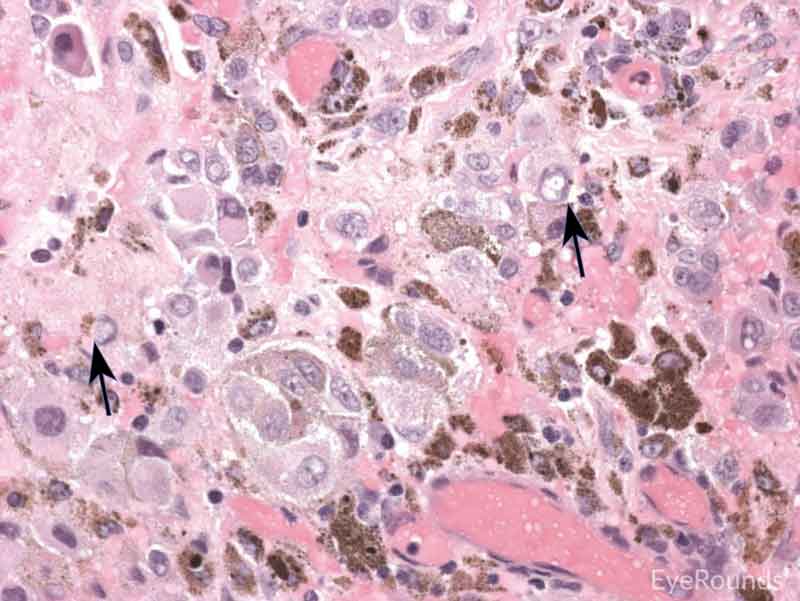

Malignant conjunctival melanoma is composed of invasive anaplastic melanocytes, which invade the underlying basement membrane of the substantia propria (Figure 6). [14] Invasion may be noted within the vessels, lymphatics, sclera, or cornea. It is important to evaluate deep and peripheral margins for tumor invasion, which requires careful tissue handling at the time of biopsy. Adjacent areas of PAM with atypia or nevi can be noted.

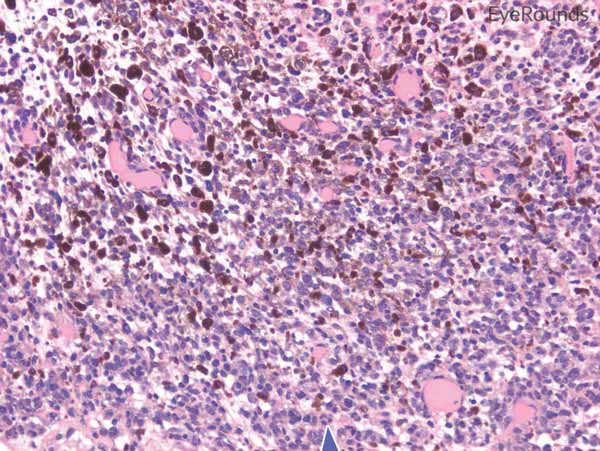

Primary acquired melanosis (PAM)is identified as abnormal, prominent intraepithelial melanocytes secondary to increased melanin and/or hyperplasia of melanocytes within the conjunctiva. Further classification is based upon presence and growth pattern of melanocytic hyperplasia, as well as the presence of atypical melanocytes. PAM without atypia is characterized by minimal melanocytic hyperplasia with minimal atypia of melanocytes. PAM with atypia is characterized by nests of atypical melanocytes and melanocytic hyperplasia. Atypia of melanocytes is defined by abnormally large cells, high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, and prominent nucleoli with mitotic figures (Figure 7).

The typical melanocytic conjunctival nevus displays conjunctival architecture composed of nests of benign melanocytes within the superficial substantia propria and epithelium. [13] Inclusion cysts are frequently noted in the conjunctiva (Figure 8 and 9). Nevi tend to migrate deeper as patients age.

While clinical characteristics may suggest a lesion is PAM or conjunctival nevi, any concern or uncertainty in diagnosis should be confirmed by biopsy.

|

|

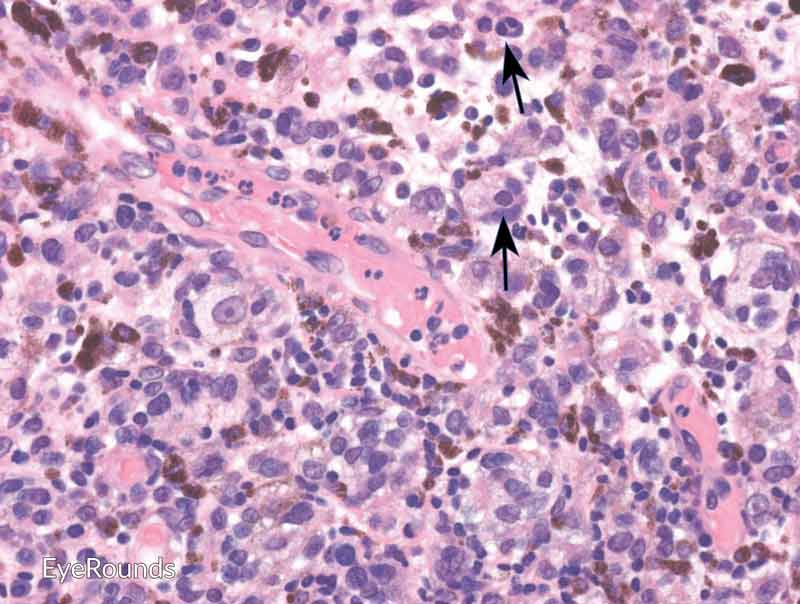

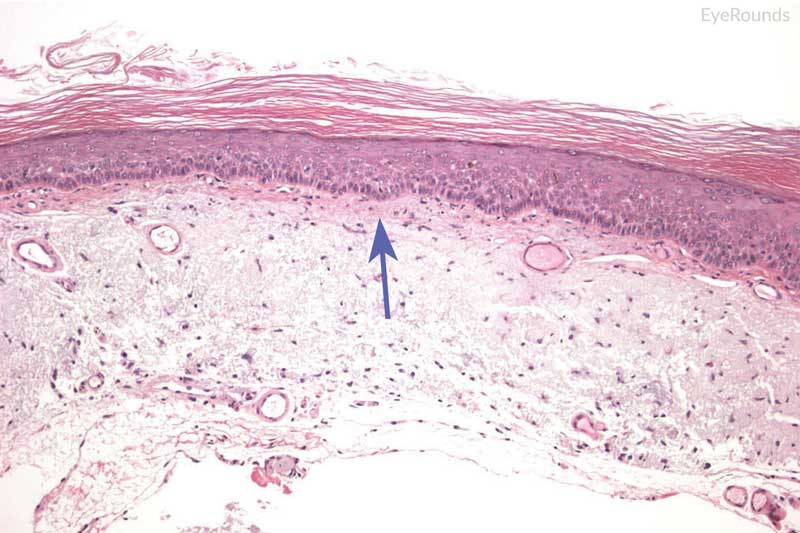

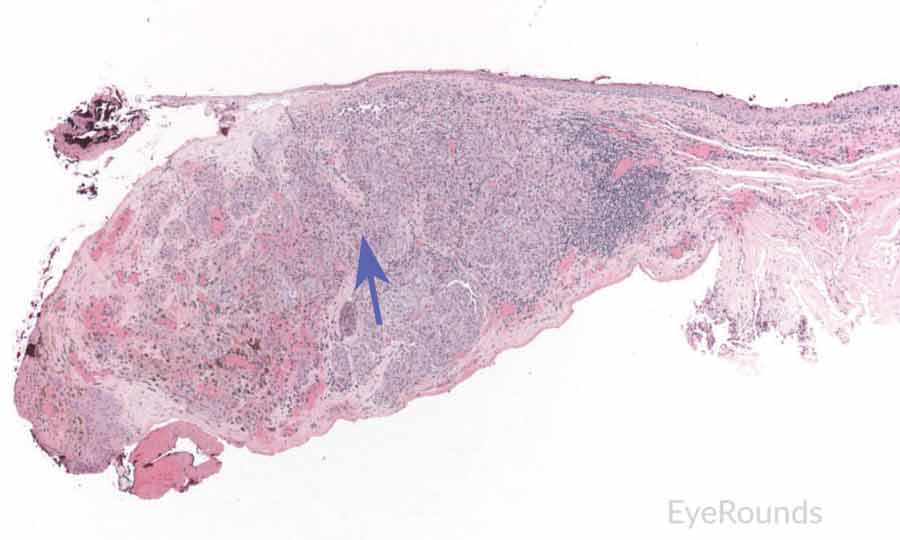

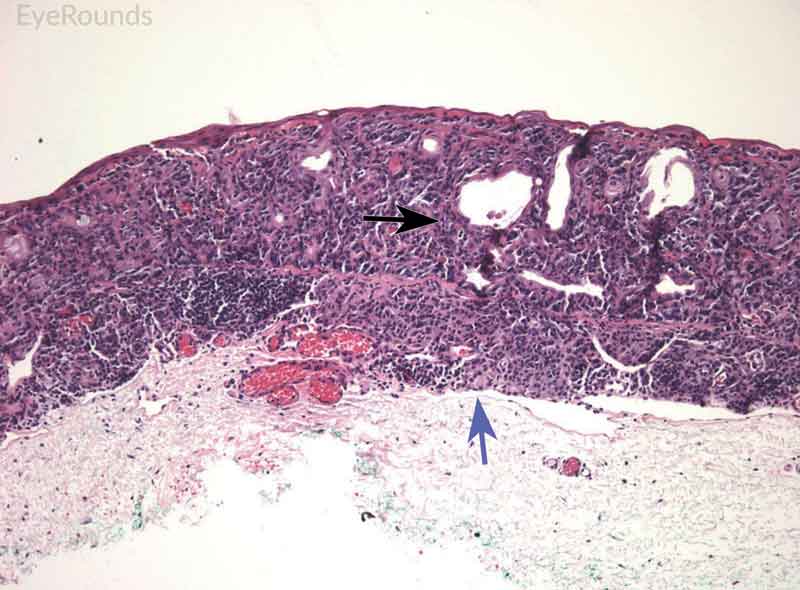

Figure 6: Invasive conjunctival melanoma

Hematoxylin and eosin stain displaying malignant melanoma invading the underlying substantia propria (blue arrow). Cytologically, the cells are notable for dysplastic features and prominent nucleoli with irregular shape and chromatin (black arrow).

|

|

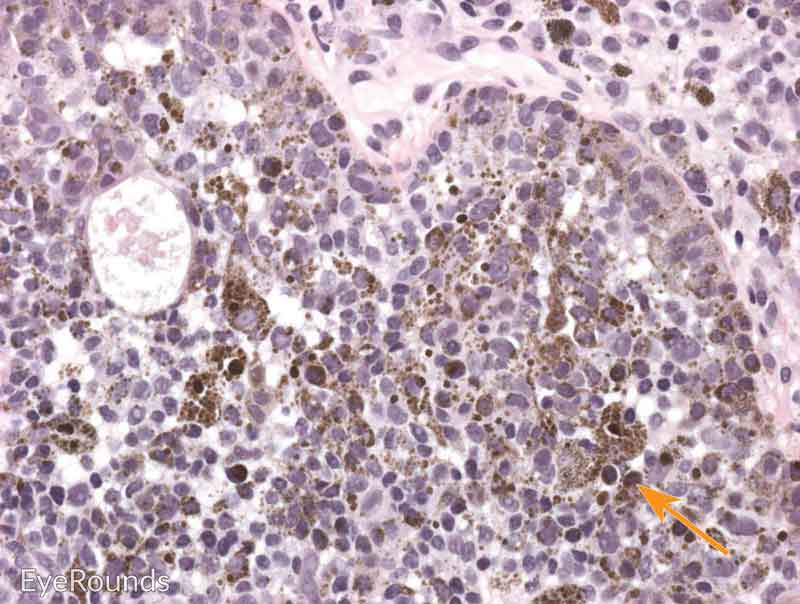

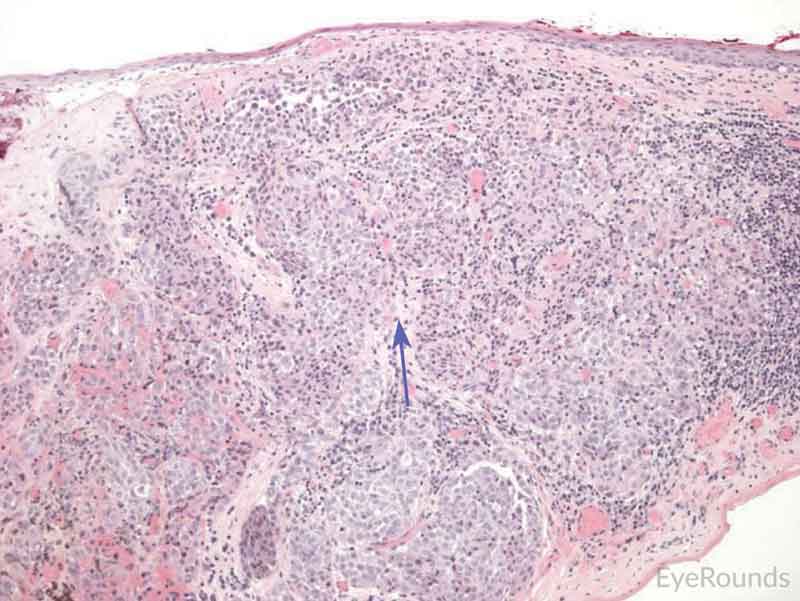

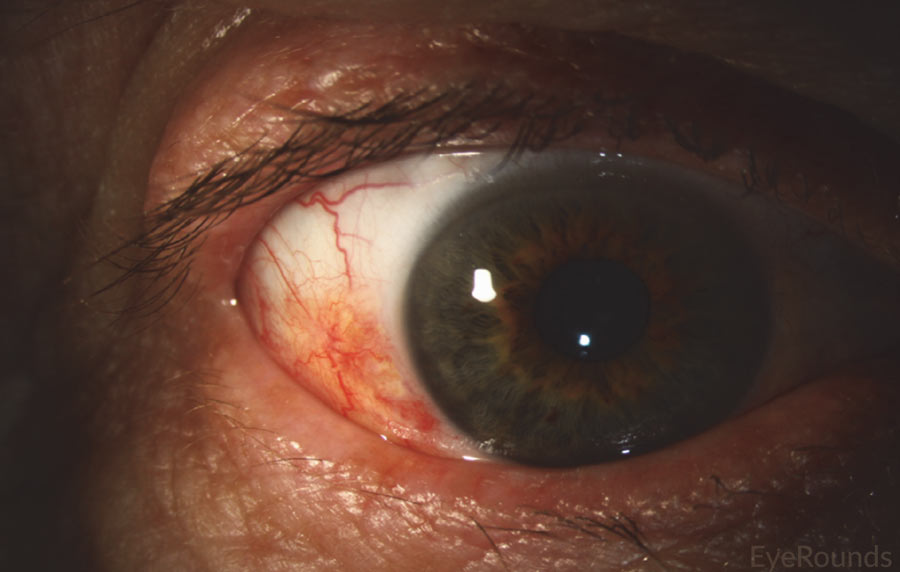

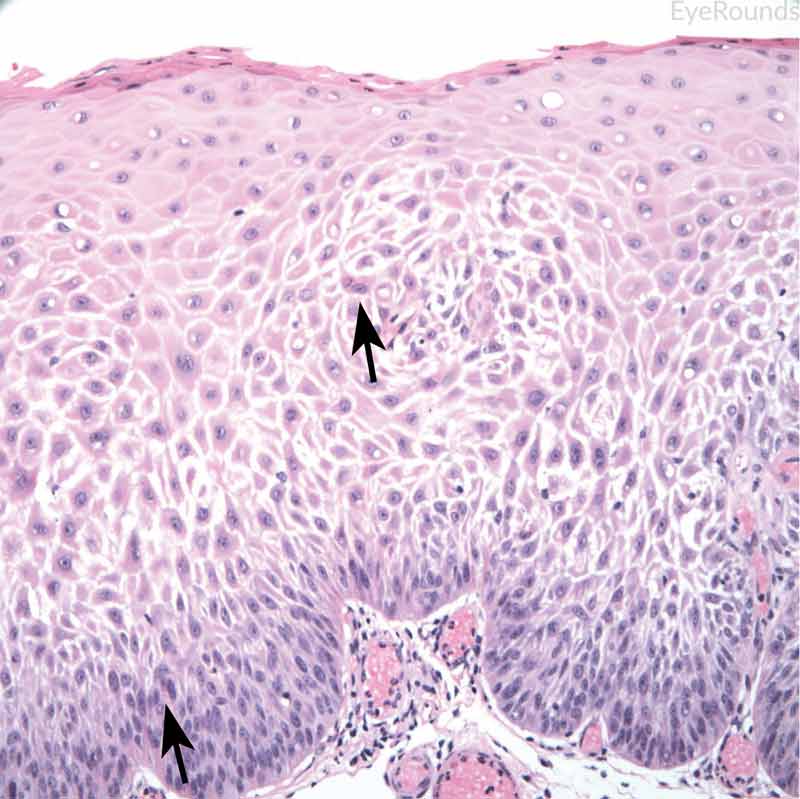

Figure 7: Primary acquired melanosis with severe atypia

Hematoxylin and eosin stain displaying PAM. The cells are characterized by abnormal melanocytes at the basal layer. Note abnormal melanocytes with dysplastic appearing nuclei (black arrow) and full thickness infiltration (blue arrow) of melanocytic cells.

|

|

|

|

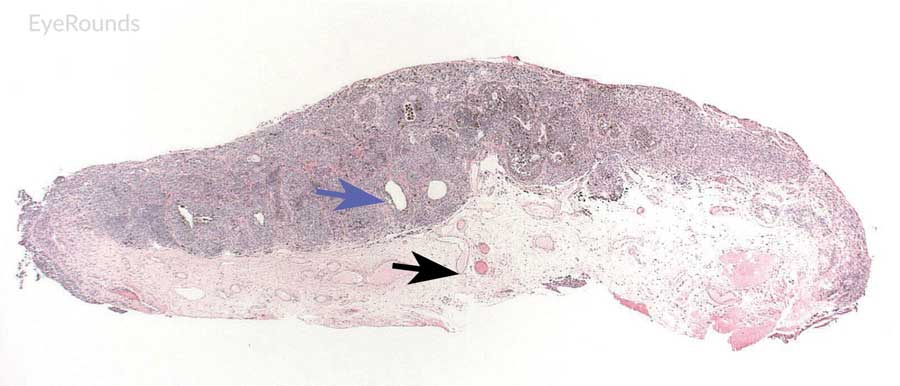

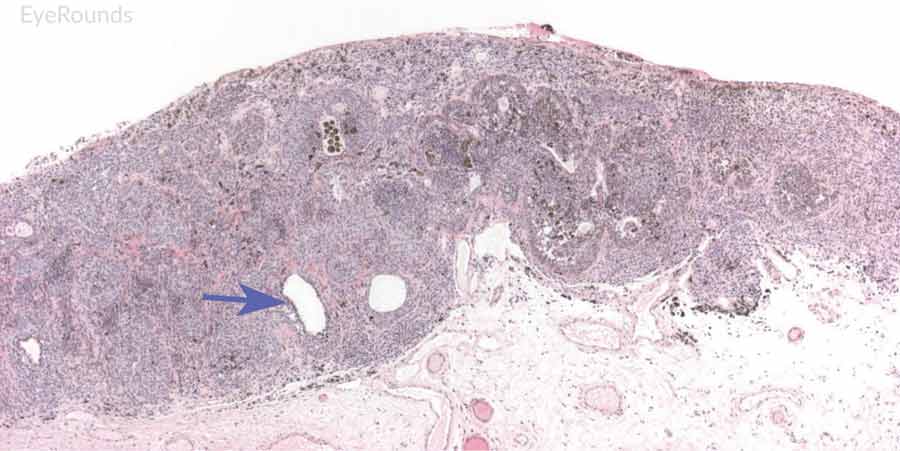

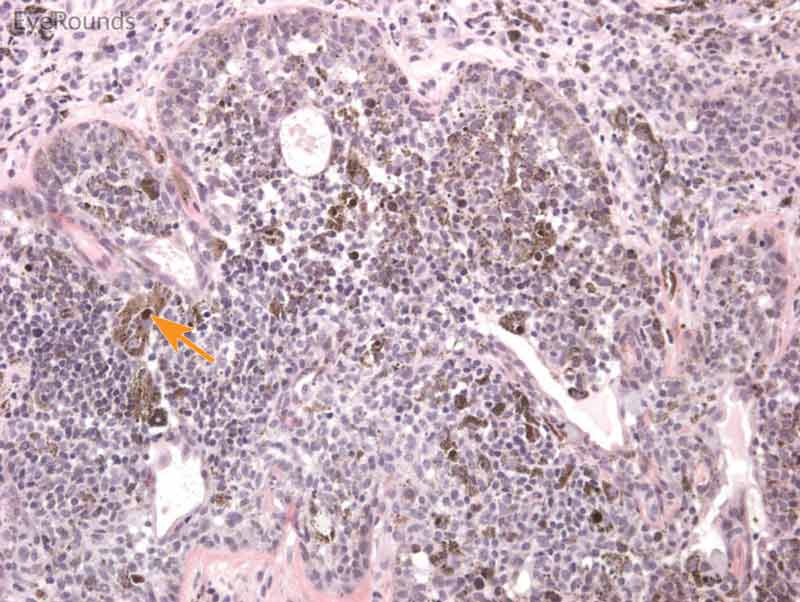

Figure 8: Conjunctival nevus

Hematoxylin and eosin stain displaying conjunctival nevus. Note the diffuse infiltration of melanocytes without atypia or dysplastic features (orange arrows). Note the cysts within the lesion (blue arrow) and intact substantia propria (black arrow).

|

|

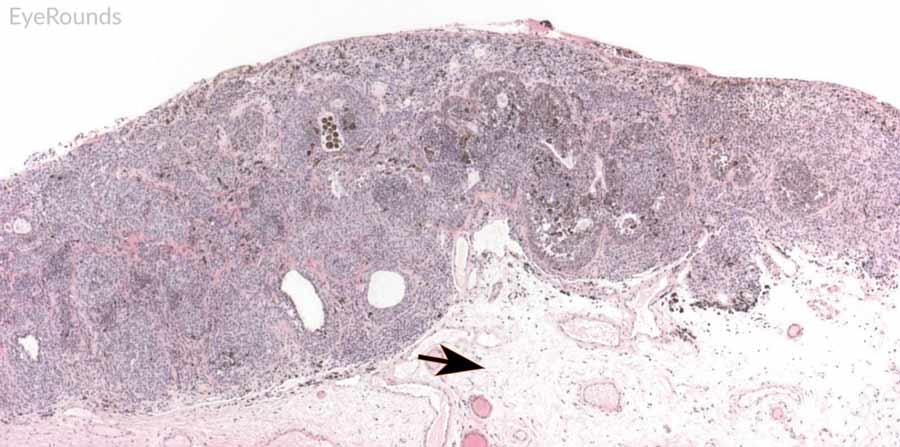

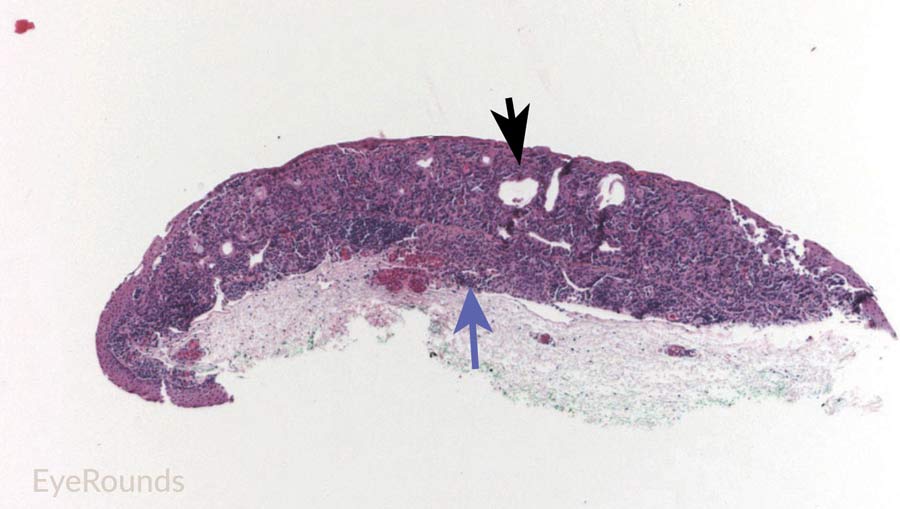

Figure 9: Junctional conjunctival nevus

Hematoxylin and eosin stain displaying conjunctival nevus from young patient at the border of the basal epithelial layer and underlying substantia propria (blue arrow). Note the cysts within the lesion (black arrow).

The surgical management of any suspicious pigmented conjunctival lesion is a complete excisional biopsy of the lesion with cryotherapy to the surrounding conjunctiva. At the University of Iowa, our preferred practice pattern is excisional biopsy with 4-5 mm of clear margins using a no-touch technique (topical absolute alcohol before and, if possible, after excision as long as not located over a muscle) with adjuvant cryotherapy, double freeze-thaw, and ocular surface reconstruction with amniotic membrane grafting. [15] Adjuvant post-excisional therapies include topical and/or subconjunctival injection of interferon alpha-2b, topical mitomycin C, brachytherapy, or external beam radiotherapy and proton beam radiotherapy, which are typically reserved for recurrent cases. No consensus exists regarding the best adjuvant treatment. Rarely, enucleation is indicated due to intraocular invasion or exenteration is indicated due to unresectable orbital invasion though there is no survival benefit. [16]

Video 1. Conjunctival Melanoma: "No Touch" Excisional Biopsy

If video fails to load, use this link: https://youtu.be/ESETk1l5kfw

Video 2. Conjunctival Melanoma - Excisional Biopsy with Lamellar Sclerokeratectomy

If video fails to load, use this link: https://youtu.be/znvJSwa9If0

Currently, there are no guidelines for systemic evaluation for metastases, with different institutions following local practice patterns. In general, positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scans, chest x-ray, liver ultrasound and liver function tests (LFTs) can be performed. Sentinel lymph node biopsies may be performed for tumors greater than 2 mm in thickness or in cases in which there is a higher degree of suspicion for metastasis such as recurrent biopsy-proven melanoma. [17]

Ocular surface melanoma related mortality rates at 10 years are 25-30%. [4] The most common locations for metastases are the lungs, brain, liver, skin, and bones. [17] Local recurrence occurs in up to 40% of cases, with risk factors including: thickness of primary tumor (greater than 2 mm), incomplete excision at the time of surgery, non-limbal tumor location (fornix, semilunar fold, caruncle, or tarsal conjunctiva), and older patient age. [6] Tumors at the caruncle portend the worst prognosis, with up to 50% mortality at 3 years (Table 2).

Table 2.

| Prognostic Indicators for Conjunctival Melanoma | |

| Higher Risk | Lower Risk |

| Tarsus, caruncle, forniceal involvement | Localized |

| Deeper extension into tissue | Limbal or bulbar |

| Thickness >1.8 mm | Thin |

| Lymphadenopathy | |

| Lid margin involvement | |

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) is the most common type of primary ocular surface neoplasm. It consists of a broad range of pathologic squamous cell dysplasia including: conjunctival and corneal intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), with mild, moderate, and severe atypia, carcinoma in situ, and invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). [18] OSSN is rare, with incidence of 0.02-3.5 per 100,000, and most commonly affects older adults. There is greater incidence near the equator. [19] Risk factors include male gender, advanced age, exposure to tobacco smoke, ultraviolet B light, chemical exposure, human papillomavirus virus (HPV) infection types 16 and 18, and immunosuppression including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). [20]

OSSN clinical manifestations occurs on a spectrum. Most lesions are pathologically benign, such as papillomas or actinic keratosis. However, other lesions are more nefarious, such as carcinoma in situ and invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

OSSN appears on slit lamp biomicroscopy as a poorly defined gelatinous lesion, usually blending with surrounding conjunctiva. There is typically an abrupt transition from normal to dysplastic epithelium. [22] Conjunctival carcinoma in situ appears as a papillary mass, usually near the limbus, with minimal leukoplakia (Figure 10). Invasive squamous cell carcinoma, representing the final stage of malignancy (occurring in less than 2% of cases), manifests as a raised, poorly defined, gelatinous lesion with or without leukoplakia. Feeder vessels often supply invasive masses, and as the lesion becomes more advanced, there is decreasing mobility of the tumor due to the conjunctiva becoming fixed to the deeper sclera. It should be noted that carcinoma in situ and invasive squamous cell carcinoma can be very difficult to differentiate at the slit lamp. Thus, biopsy is very helpful in making the diagnosis.

|

|

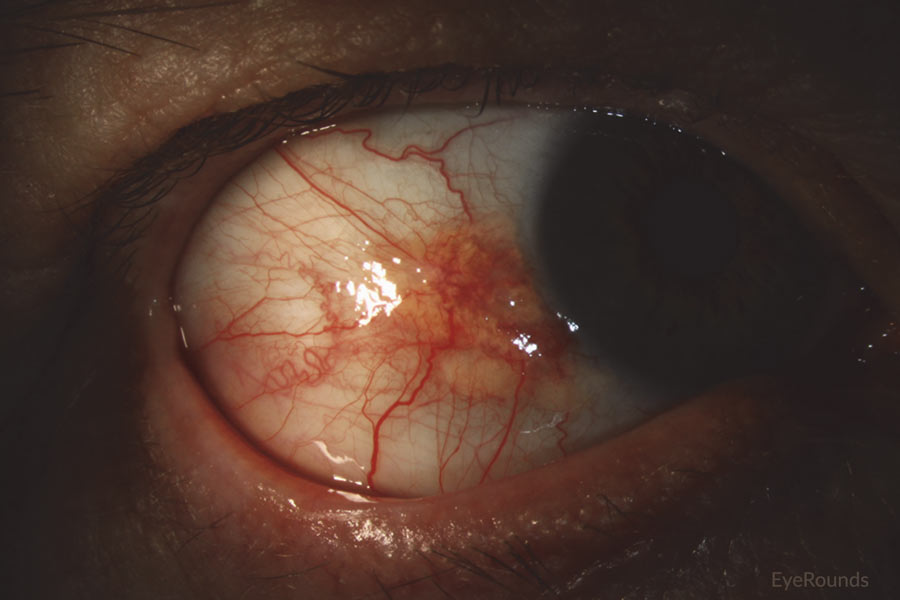

Figure 10: Conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in situ

Slit lamp photograph displaying patchy, limbal-based gelatinous mass. Vascular engorgement is noted. This is an example of carcinoma in situ.

The gold standard for diagnosis is histopathological evaluation following biopsy. Carcinoma in situ is characterized by full-thickness replacement of the epithelium with anaplastic cells; however, the basement membrane remains intact and the underlying substantia propria is not affected. Histology displays a mixture of spindle and epidermoid cells, with disorganization of cells, increased nuclear to cytoplasm ratio, and abnormal polarity. There is generally a characteristic demarcation between diseased epithelium and adjacent normal tissue (Figure 11). [24] Invasive squamous cell carcinoma is characterized by severely anaplastic cells with penetration of the basement membrane and extension into the underlying stromal tissue (Figure 12). As the tumor invades, it can appear as cords of invasive cells or as broad, expansive fronds. [24] Spindle cell carcinoma and mucoepidermoid cell carcinoma are variants representing more invasive tumors.

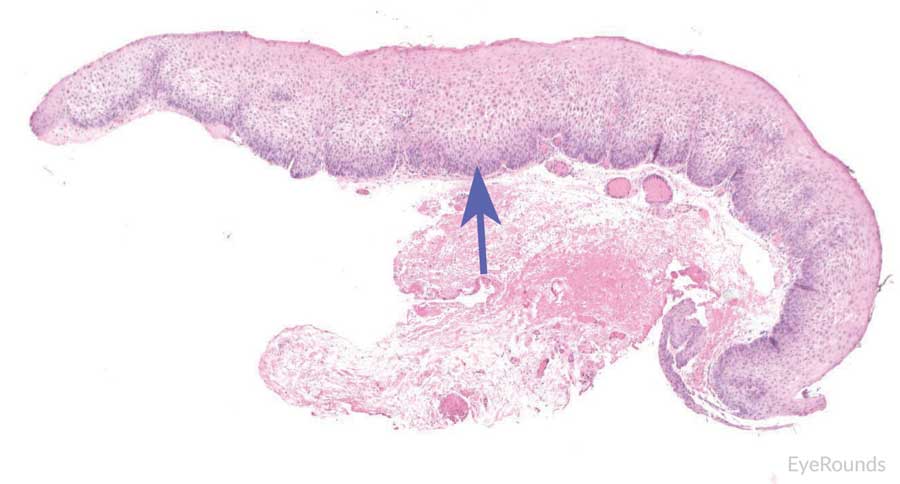

Figure 11: Carcinoma in situ

Hematoxylin and eosin stain displaying full thickness dysplastic changes, without extension below basal epithelial layer (blue arrow).

|

|

Figure 12: Invasive conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma

Hematoxylin and eosin stain displaying full thickness squamous cell carcinoma (blue arrow) with breakthrough of basement membrane. Image on right displays acanthosis, dyskeratosis, and bizarre cells (black arrow).

Adequate treatment of squamous cell neoplasms depends upon the clinical characteristics of the lesions. Factors such as size, location, and invasiveness of the tumor influence the appropriate treatment of neoplasms. For discrete masses, complete excision with adequate margins is the treatment of choice, often aided by alcohol epitheliectomy. It is important to ensure adequate margins, which may include up to 3-4 mm of uninvolved conjunctiva. Most surgeons will apply double freeze thaw cryotherapy to the adjacent bulbar conjunctiva in order to provide better local control. Additionally, amniotic membrane grafts can be used to close a resection site. Other adjunctive therapies include interferon α2b, mitomycin C, and 5-flurouracil. No consensus exists for use of these therapies. [25] Interferon α2b is commonly used due to its lower risk profile. Enucleation or exenteration may be required with invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Enucleation is necessary in cases of invasion through the cornea or sclera without orbital or regional spread. Exenteration is necessary when tumor has invaded the orbit. [26]

Video 3. Conjunctival Excisional Biopsy for Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia

If video fails to load, use this link: https://vimeo.com/169300308Outcomes for squamous cell tumors are related to the degree of aggressiveness of the tumors. For carcinoma in situ, patients with completely excised tumors have great outcomes, with risk of local recurrence around 2% and regional lymph node metastasis at around 1%. [27] If there is a recurrence, more aggressive resection as well as use of adjunctive therapies may be required. In cases of invasive squamous cell carcinoma with complete resection the rate of local recurrence is 5%, with approximately 2% displaying regional lymph node metastases. [28]

Lymphoid tumors of the conjunctiva can present on a spectrum from benign to malignant disease. Benign tumors are reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, intermediate lesions present as atypical lymphoid hyperplasia, and malignant tumors are lymphomas. Lymphoid tumors of the conjunctiva are very rare, and the exact incidence is unknown. In a large series of conjunctival tumors, Shields et al. noted 128 lymphoid lesions out of 1634 total tumors. [29] Malignant lymphomas tend to occur in older adults, while benign lymphoid tumors tend to occur in younger patients. Known risk factors for malignancy include older age, history of systemic lymphoma, and immunosuppression. [30]

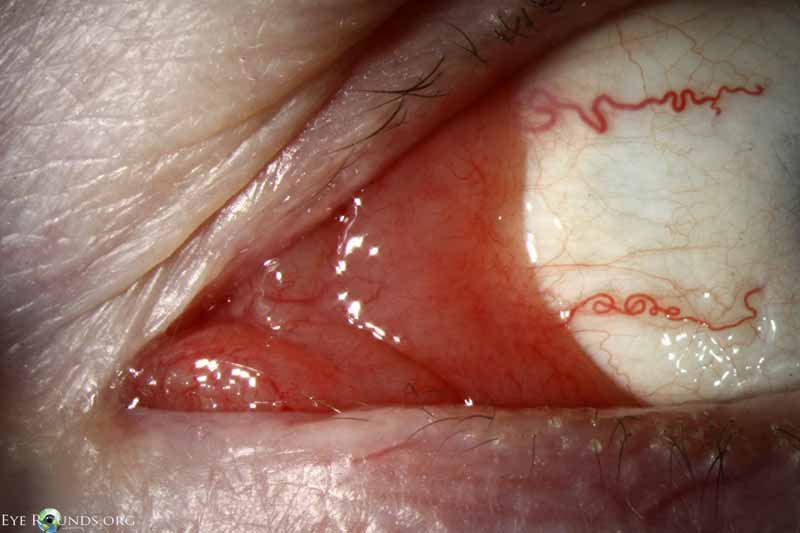

Conjunctival lymphoid tumors appear as salmon colored, smooth, elevated lesions of the bulbar or forniceal conjunctiva (Figures 13 & 14). There is a predisposition for the inferior fornix. [31] Nasal lesions have poor outcomes due to potentially deeper extension into surrounding tissue. Bilateral involvement is present in up to 20% of all patients, although the lesions tend to be asymmetric. Importantly, systemic lymphoma develops in 17% of patients with unilateral lesions and in 47% of patients with bilateral disease. [31] It is difficult to differentiate benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia from malignant lymphoma on slit lamp exam. Thus, excisional biopsy is required for diagnosis.

Figure 13: Conjunctival benign lymphoid hyperplasia

Slit lamp photo displaying superior conjunctival lesion with characteristic salmon patch appearance.

|

|

Figure 14: Conjunctival lymphoma

Slit lamp photo displaying salmon patch lesion extending into the semilunaris and caruncle.

It is important to obtain immunofluorescence testing and fresh samples for appropriate pathological diagnosis. Benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia is characterized by polymorphic, well-differentiated lymphocytes and possibly plasma cells. These cells tend to have well-developed germinal centers. Lymphomas are monomorphic, without germinal centers. Flow cytometry is helpful in determining whether cells are monoclonal or polyclonal, whether cells are B or T cells, and if DNA abnormalities are present. The majority of conjunctival lymphomas are B cell lymphomas (68-81%). [32,33]

Treatment of lymphoid tumors depends upon the underlying diagnosis. In a patient with a suspected lymphoid tumor, a complete medical workup for systemic lymphoma is warranted. Included in the initial investigation is a history and physical, complete blood count with differential, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brain and orbits, as well as PET scan to identify a systemic lymphoma. In addition to a comprehensive evaluation, excisional biopsy should be completed to identify the underlying pathology. In the case of benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, treatment can be observation or topical steroids for a few weeks. In the case of low-grade lymphoid neoplasm, low-dose external beam radiation therapy is recommended. In the case of high-grade lymphoma, higher dose external beam radiation is recommended (usually 40-45Gy). [34] Generally, lymphomas respond well to radiation. If systemic lymphoma is discovered on workup, then treatment consists of chemotherapy with or without radiation. [30]

Patients with benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia have a very good prognosis, and lesions generally resolve with excision, steroids, or observation. Most localized lymphomas respond well to excision and radiation. In patients with systemic lymphoma, chemotherapy is often indicated for treatment, with rituximab as the treatment of choice., A recent study reported that the 10-year progression free survival in bilateral disease is 48% compared to 72% survival rate in those with unilateral disease. [35] Due to risk of recurrence, patients with lymphoma should be followed indefinitely, with follow up every 3 months for the first year, and every 6-12 months thereafter. [36]

- Seregard S. Conjunctival melanoma. Surv Ophthalmol 1998;42(4):321-350. https://PubMed.gov/9493274

- Isager P, Osterlind A, Engholm G, Heegaard S, Lindegaard J, Overgaard J, Storm HH. Uveal and conjunctival malignant melanoma in Denmark, 1943-97: incidence and validation study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2005;12(4):223-232. https://PubMed.gov/16033743 . DOI: 10.1080/09286580591000836

- McLaughlin CC, Wu XC, Jemal A, Martin HJ, Roche LM, Chen VW. Incidence of noncutaneous melanomas in the U.S. Cancer 2005;103(5):1000-1007. https://PubMed.gov/15651058 . DOI: 10.1002/cncr.20866

- Shields CL, Shields JA, Gunduz K, Cater J, Mercado GV, Gross N, Lally B. Conjunctival melanoma: risk factors for recurrence, exenteration, metastasis, and death in 150 consecutive patients. Arch Ophthalmol 2000;118(11):1497-1507. https://PubMed.gov/11074806

- Gandini S, Sera F, Cattaruzza MS, Pasquini P, Zanetti R, Masini C, Boyle P, Melchi CF. Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: III. Family history, actinic damage and phenotypic factors. Eur J Cancer 2005;41(14):2040-2059. https://PubMed.gov/16125929 . DOI: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.03.034

- Wong JR, Nanji AA, Galor A, Karp CL. Management of conjunctival malignant melanoma: a review and update. Expert Rev Ophthalmol 2014;9(3):185-204. https://PubMed.gov/25580155 . DOI: 10.1586/17469899.2014.921119

- Hurst EA, Harbour JW, Cornelius LA. Ocular melanoma: a review and the relationship to cutaneous melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2003;139(8):1067-1073. https://PubMed.gov/12925397 . DOI: 10.1001/archderm.139.8.1067

- Yu GP, Hu DN, McCormick S, Finger PT. Conjunctival melanoma: is it increasing in the United States? Am J Ophthalmol 2003;135(6):800-806. https://PubMed.gov/12788119

- Shields JA, Shields CL, Mashayekhi A, Marr BP, Benavides R, Thangappan A, Phan L, Eagle RC, Jr. Primary acquired melanosis of the conjunctiva: experience with 311 eyes. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2007;105:61-71; discussion 71-62. https://PubMed.gov/18427595

- Shields CL, Markowitz JS, Belinsky I, Schwartzstein H, George NS, Lally SE, Mashayekhi A, Shields JA. Conjunctival melanoma: outcomes based on tumor origin in 382 consecutive cases. Ophthalmology 2011;118(2):389-395 e381-382. https://PubMed.gov/20723990 . DOI: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.06.021

- Gloor P, Alexandrakis G. Clinical characterization of primary acquired melanosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1995;36(8):1721-1729. http://iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2161849

- Gerner N, Norregaard JC, Jensen OA, Prause JU. Conjunctival naevi in Denmark 1960-1980. A 21-year follow-up study. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 1996;74(4):334-337. https://PubMed.gov/8883545

- Folberg R, Jakobiec FA, Bernardino VB, Iwamoto T. Benign conjunctival melanocytic lesions. Clinicopathologic features. Ophthalmology 1989;96(4):436-461. https://PubMed.gov/2657539

- Jakobiec FA, Folberg R, Iwamoto T. Clinicopathologic characteristics of premalignant and malignant melanocytic lesions of the conjunctiva. Ophthalmology 1989;96(2):147-166. https://PubMed.gov/2649838

- Shields JA, Shields CL, De Potter P. Surgical management of circumscribed conjunctival melanomas. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;14(3):208-215. https://PubMed.gov/9612814

- Rodriguez-Reyes AA, Rios y Valles-Valles D, Corredor-Casas S, Gomez-Leal A. Advanced conjunctival melanoma. Can J Ophthalmol 2004;39(4):453-460. https://PubMed.gov/15327112

- Esmaeli B. Regional lymph node assessment for conjunctival melanoma: sentinel lymph node biopsy and positron emission tomography. Br J Ophthalmol 2008;92(4):443-445. https://PubMed.gov/18369054 . DOI: 10.1136/bjo.2007.131615

- Lee GA, Hirst LW. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Surv Ophthalmol 1995;39(6):429-450. https://PubMed.gov/7660300

- Kiire CA, Dhillon B. The aetiology and associations of conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90(1):109-113. https://PubMed.gov/16361679 . DOI: 10.1136/bjo.2005.077305

- Karcioglu ZA, Wagoner MD. Demographics, etiology, and behavior of conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in the 21st century. Ophthalmology 2009;116(11):2045-2046. https://PubMed.gov/19883851 . DOI: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.09.031

- Sjo N, Heegaard S, Prause JU. Conjunctival papilloma. A histopathologically based retrospective study. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2000;78(6):663-666. https://PubMed.gov/11167228

- Shields CL, Shields JA. Tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea. Surv Ophthalmol 2004;49(1):3-24. https://PubMed.gov/14711437

- Tunc M, Char DH, Crawford B, Miller T. Intraepithelial and invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva: analysis of 60 cases. Br J Ophthalmol 1999;83(1):98-103. https://PubMed.gov/10209445

- Mittal R, Rath S, Vemuganti GK. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia - Review of etio-pathogenesis and an update on clinico-pathological diagnosis. Saudi J Ophthalmol 2013;27(3):177-186. https://PubMed.gov/24227983 . DOI: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2013.07.002

- Sayed-Ahmed IO, Palioura S, Galor A, Karp CL. Diagnosis and Medical Management of Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia. Expert Rev Ophthalmol 2017;12(1):11-19. https://PubMed.gov/28184236 . DOI: 10.1080/17469899.2017.1263567

- Shields CL, Chien JL, Surakiatchanukul T, Sioufi K, Lally SE, Shields JA. Conjunctival Tumors: Review of Clinical Features, Risks, Biomarkers, and Outcomes--The 2017 J. Donald M. Gass Lecture. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2017;6(2):109-120. https://PubMed.gov/28399347 . DOI: 10.22608/APO.201710

- Honavar SG, Manjandavida FP. Tumors of the ocular surface: A review. Indian J Ophthalmol 2015;63(3):187-203. https://PubMed.gov/25971163 . DOI: 10.4103/0301-4738.156912

- Tabin G, Levin S, Snibson G, Loughnan M, Taylor H. Late recurrences and the necessity for long-term follow-up in corneal and conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Ophthalmology 1997;104(3):485-492. https://PubMed.gov/9082277

- Shields CL, Demirci H, Karatza E, Shields JA. Clinical survey of 1643 melanocytic and nonmelanocytic conjunctival tumors. Ophthalmology 2004;111(9):1747-1754. https://PubMed.gov/15350332 . DOI: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.013

- Tsai PS, Colby KA. Treatment of conjunctival lymphomas. Semin Ophthalmol 2005;20(4):239-246. https://PubMed.gov/16352495 . DOI: 10.1080/08820530500350845

- Shields CL, Shields JA, Carvalho C, Rundle P, Smith AF. Conjunctival lymphoid tumors: clinical analysis of 117 cases and relationship to systemic lymphoma. Ophthalmology 2001;108(5):979-984. https://PubMed.gov/11320031

- Coupland SE, Krause L, Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Foss HD, Hummel M, Bornfeld N, Lee WR, Stein H. Lymphoproliferative lesions of the ocular adnexa. Analysis of 112 cases. Ophthalmology 1998;105(8):1430-1441. https://PubMed.gov/9709754 . DOI: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)98024-1

- Knowles DM, Jakobiec FA, McNally L, Burke JS. Lymphoid hyperplasia and malignant lymphoma occurring in the ocular adnexa (orbit, conjunctiva, and eyelids): a prospective multiparametric analysis of 108 cases during 1977 to 1987. Hum Pathol 1990;21(9):959-973. https://PubMed.gov/2394438

- Uno T, Isobe K, Shikama N, Nishikawa A, Oguchi M, Ueno N, Itami J, Ohnishi H, Mikata A, Ito H. Radiotherapy for extranodal, marginal zone, B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue originating in the ocular adnexa: a multiinstitutional, retrospective review of 50 patients. Cancer 2003;98(4):865-871. https://PubMed.gov/12910532 . DOI: 10.1002/cncr.11539

- Kirkegaard MM, Rasmussen PK, Coupland SE, Esmaeli B, Finger PT, Graue GF, Grossniklaus HE, Honavar SG, Khong JJ, McKelvie PA, Mulay K, Prause JU, Ralfkiaer E, Sjo LD, Toft PB, Vemuganti GK, Thuro BA, Curtin J, Heegaard S. Conjunctival Lymphoma--An International Multicenter Retrospective Study. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016;134(4):406-414. https://PubMed.gov/26891973 . DOI: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.6122

- Tanimoto K, Kaneko A, Suzuki S, Sekiguchi N, Maruyama D, Kim SW, Watanabe T, Kobayashi Y, Kagami Y, Maeshima A, Matsuno Y, Tobinai K. Long-term follow-up results of no initial therapy for ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma. Ann Oncol 2006;17(1):135-140. https://PubMed.gov/16236754 . DOI: 10.1093/annonc/mdj025

- Rath S, Connors JM, Dolman PJ, Rootman J, Rootman DB, White VA. Comparison of American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM-based staging system (7th edition) and Ann Arbor classification for predicting outcome in ocular adnexal lymphoma. Orbit 2014;33(1):23-28. https://PubMed.gov/24180616 . DOI: 10.3109/01676830.2013.842257

Suggested Citation Format

Benage M, Fox AR, Boyce MR, Greiner MA, with Syed NA. Ocular Surface Tumors. EyeRounds.org. posted December 20, 2017; Available from: https://eyerounds.org/tutorials/Ocular-Surface-Tumors/