The University of Iowa

Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences

June 14, 2017

A thorough ophthalmic examination should always include careful inspection of the external periocular tissues. These tissues include specialized structures that are prone to unique pathology. For example, the eyelid has cilia, sebaceous glands of Zeis, apocrine sweat glands of Moll, eccrine sweat glands, and vellus hairs. Deep to the eyelid dermis lays the orbicularis muscle followed by the tarsal plate containing the sebaceous Meibomian glands and ducts. These structures can give rise to both benign and malignant proliferations. Here we discuss those that are malignant. Please refer to this article to see benign eyelid lesions. The following discussion includes the presentation and pathology of common eyelid malignancies. This is meant to be an overview and tutorial. Additionally, treatment options are briefly discussed but are not exhaustive. Treatment of these malignant tumors depends on the extent of invasion as well as lymph node and systemic involvement.

Keratoacanthoma is a rare tumor usually occurring in fair-skinned individuals over areas of chronic sun exposure or sites of prior trauma. Most commonly occurs during the 6th decade of life. They are regarded as part of the spectrum of squamous cell carcinomas. These are more common in immunocompromised individuals. Some classify keratoacanthoma as a low grade malignancy and refer to them as "squamous cell carcinoma with keratoacanthoma-like features".[1]

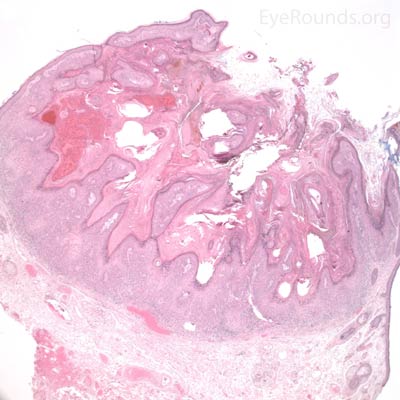

Classically presents as a flesh colored to erythematous elevated nodule with a central keratin plug on the lower eyelid. These lesions grow quickly, up to 2.5 cm over 2-4 weeks, followed by a slower involutional phase taking several months. During involution, a keratin-filled crater may form and if left alone, a permanent, depressed scar remains.

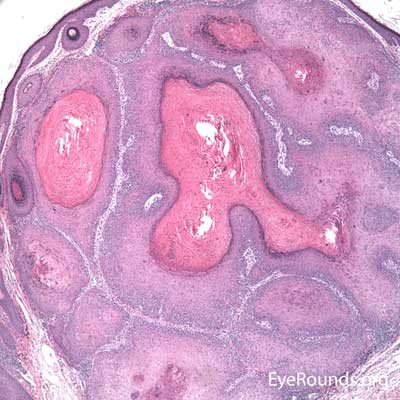

Typical pathologic specimens show a lymphocytic infiltrate at the base of the lesion and eosinophilic epithelium. The epidermis is acanthotic and often shows some nuclear atypia, dyskeratosis, squamous eddies and an increased mitotic rate. The proliferating epithelial cells will frequently undermine the adjacent normal epidermis, leading to a sharp transition between normal and thickened epithelium known as shoulder formation

Cutaneous horns erupting from keratocanomas indicate a higher likelihood of underlying squamous cell carcinoma.

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common human malignancy and by far the most common eyelid malignancy, accounting for about 90% of malignant lesions on the eyelid. It most frequently affects fair-skinned, elderly patients with peak incidence at age 70. Risk factors include ultraviolet light exposure, age, chronic inflammation, immunosuppression, and exposure to arsenic and coal tar derivatives. [2].

Basal cell carcinoma usually presents as a flesh colored to pearly, raised nodule with rolled edges. Some ulcerate or have telangiectatic vessels on the surface. From most to least common location, BCCs arise on the lower eyelid, medial canthus, upper eyelid, and lateral canthus. Many variants of BCC exist including nodular (>50% of cases), pigmented, superficial, cystic, and morpheaform. While they can invade locally and extensively, BCC grows slowly and has a very low rate of metastasis.

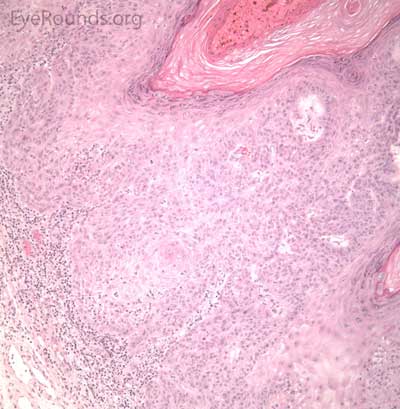

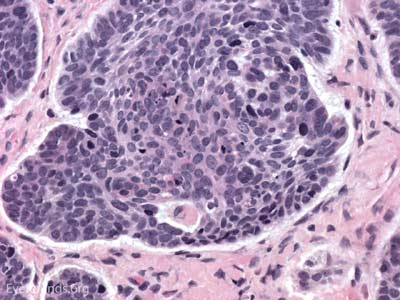

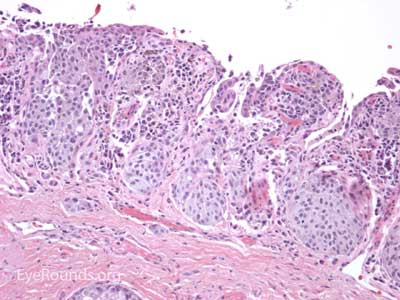

BCC arises from the epidermis and invades into the dermis forming basophilic islands of tumor that typically have a palisading "picket fence" border that mimics the hair matrix. Tumor cells are characterized by relatively bland, monomorphous nuclei with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. Single cell necrosis is common within the islands. The islands are often separated from the surrounding dermis by an artifactitious clear space (retraction artifact).

BCCs of greatest concern are those arising near the medial canthus where they can more easily invade the orbit and sinuses. These are the most difficult to manage and carry a high risk of recurrence.

Actinic keratosis is a precancerous dysplastic squamous lesion that results from proliferation of atypical epidermal keratinocytes which have the ability to transform into squamous cell carcinoma. Major risk factors for AK include UV light exposure and fair skin. Although easily managed, the occurrence of AKs should increase clinical suspicion for other skin malignancies. [3]

AKs typically present as erythematous, scaly macules or papules. Lesions usually are < 1cm in diameter and rough to the touch. The most frequently affected areas include the face, exposed scalp, and dorsum of forearms and hands. Several clinical variants exist including classic/common, hypertrophic, atrophic, AK with cutaneous horn, and pigmented.

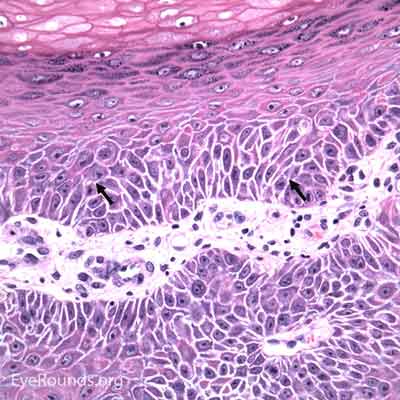

The pathology depends on the clinical variant, but classically demonstrates focal surface parakeratosis and loss of the stratum granulosum in the epidermis. There may be acanthosis with club-like extensions of the rete ridges into the dermis. Some degree of epidermal nuclear atypia is present, usually in the deeper layers of the epidermis. The superficial dermis may have a lymphocytic infiltrate at the base of the lesion. The underlying dermis usually has solar elastosis.

The risk of developing frank malignancy from actinic keratosis is grossly estimated from multiple studies. Generally accepted statistics: individuals with AKs have a 10-25% chance of developing SCC; 25% of AKs resolve spontaneously; total risk of transformation for an individual lesion is estimated at 1%. Although the risk of death from AKs is low, they should be promptly treated; prevention of future SCC is more effective than treating after one develops.

SCC is the second most common cutaneous malignancy, second only to BCC worldwide. However in dark skinned individuals, SCC is the most common skin cancer. They account for 5-10% of eyelid malignancies and may spread perineurally to invade the orbit or paranasal sinuses. The overall risk of metastasis is less than 5%, but the risk increases to 20-30% when present on lips, ears, or eyelids. Risks include UV exposure, fair skin, childhood sunburns, age, family or personal history, immunosuppression, smoking, arsenic exposure, and genetic predisposition. [4]

There is a wide variety of SCC clinical presentations ranging from papules, plaques, or nodules with smooth, hyperkeratotic, or ulcerative secondary characteristics. Most are erythematous to pink nodules with overlying scale or crust with or without ulceration. SCC is most commonly found on the head and neck (55%), but can develop on any cutaneous surface. Squamous cell carcinomas have a predilection for the lower eyelid and lid margin.

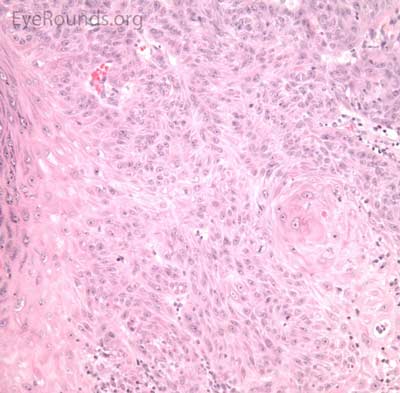

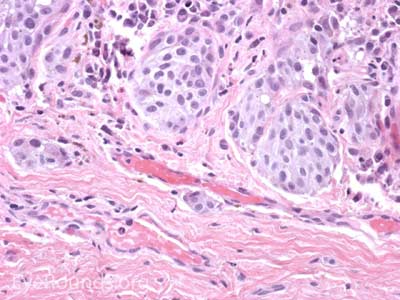

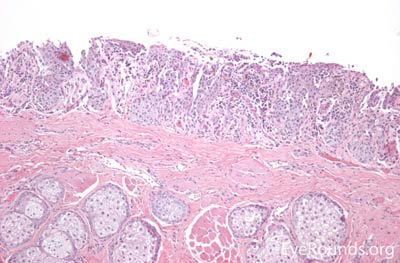

SCCs can vary from well differentiated to poorly differentiated on the eyelid. Atypical squamous cells form islands and strands extending deep to the epidermal basement membrane, infiltrating the dermis, and inciting a fibrotic dermal reaction. Prominent intercellular bridges (desmosomes) can be seen between cells. Dyskeratosis is often present in the form of horn cysts or keratin pearls. In contrast to BCC, cells are typically eosinophilic and may form whorls known as squamous eddies. SCC in situ is commonly referred to as Bowen disease

Unfortunately, SCC is at times downplayed as melanoma's less dangerous counterpart. However, among African Americans, SCC is the leading cause of mortality by skin malignancy. All suspected SCCs should be investigated further by biopsy.

The incidence of cutaneous melanoma is rising faster than any other cancer in the United States. Although rarely occurring on the eyelids, melanoma can be associated with a high mortality rate. Pigmentation remains a hallmark of this lesion, but half of eyelid melanomas are non-pigmented and may lead to misdiagnosis. Lentigo maligna is a subtype of melanoma in situ that usually occurs on the face or neck of older individuals. It is the most common melanoma subtype that affects the eyelids and has the ability to spread onto the conjunctiva. When atypical melanocytes of lentigo maligna invade the dermis, the lesion is referred to as lentigo maligna melanoma (invasive melanoma). Risk factors include UV exposure, fair skin, childhood sunburns, presence of many dysplastic nevi, and a family or personal history of melanoma. [5]

Histologic appearance of cutaneous melanoma depends on the subtype. Lentigo maligna typically presents as an irregularly pigmented, patchy, slowly expanding macule. Nodular thickening of the lesion is suggestive of an invasive component. Superficial spreading melanomas are variably pigmented macules or plaques with irregular borders and multiple color hues ranging from black to blue to brown. Nodular melanomas are usually darkly pigmented pedunculated or polypoid nodules; they can be amelanotic. In contrast to the long horizontal growth phase of lentigo maligna and superficial spreading melanoma, nodular melanomas are more worrisome because of their propensity for rapid vertical growth into dermis.

Melanoma can have several different cell types histologically (epithelioid, spindle, and balloon cells) and may be subtle, especially if lacking pigment. They exhibit two forms of atypia: Architectural atypia is described as nests of atypical, pleomorphic melanocytes proliferating in the epidermis and dermis without pattern or symmetry (lentiginous pattern). Cytologic atypia is described as high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, prominent nucleoli, and increased mitotic rate. The single most important prognostic factor for cutaneous melanoma is depth of invasion measured in hundredths of a millimeter (Breslow depth).

The physical diagnostic guidelines of melanoma apply to the periocular tissues as they do to other skin surfaces. They follow the ABCDEs of melanoma – asymmetry, border irregularities, color heterogeneity with black and blue hues, diameter >6mm, and evolution or changing of lesion over time. Both patients and ophthalmologists should follow this mantra when screening for cutaneous melanomas to ensure prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Sebaceous adenocarcinoma is an uncommon, slow-growing but potentially aggressive malignancy often affecting the elderly with a predilection for female patients. It can arise from the meibomian glands, glands of Zeis, or caruncular sebaceous glands. Approximately 80% present on the head or neck with 40% involving the eyelid. Unlike BCC and SCC, sebaceous (adeno)carcinomas occur more commonly on the upper eyelid which has more numerous meibomian glands compared with the lower eyelid. [6 ,7]

Sebaceous adenocarcinomas are notorious for masquerading as other conditions, such chalazion or ulcerative blepharoconjunctivitis. It may present as a small, rubbery, firm nodule on the upper eyelid. It may be papillomatous or present as diffuse tarsal thickening with eyelid misdirection. Madarosis (loss of eyelashes) is not uncommon. Caruncular lesions are may be multi-lobulated, grey-yellow subconjunctival masses. When arising from the glands of Zeis, the lesions form small yellow nodules in front of the grey line which can cause eyelid malposition. The yellowish appearance associated with the tumor is due to sebum and one must be suspicious of this.

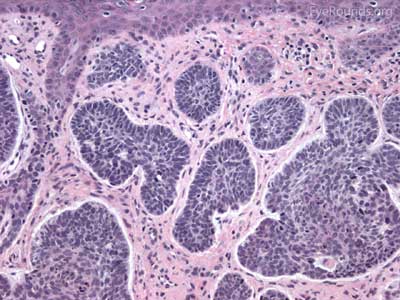

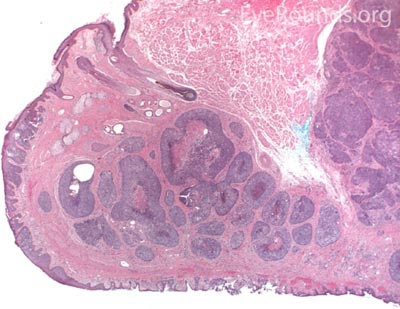

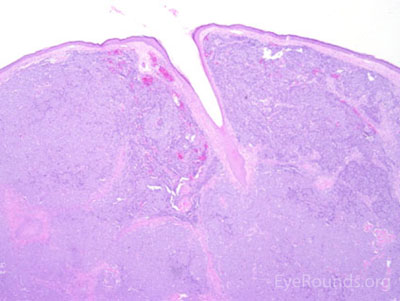

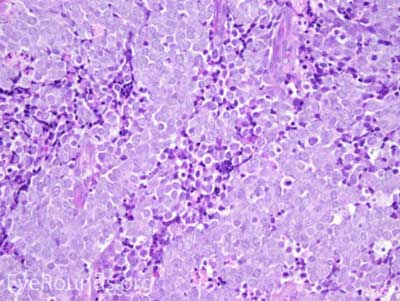

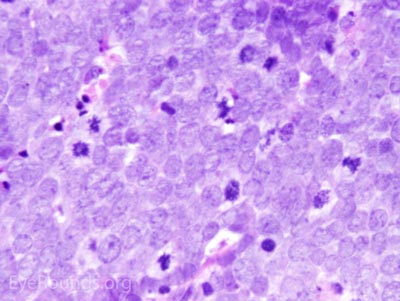

Sebaceous adenocarcinoma consists of pleomorphic, atypical epithelial cells ranging from moderately differentiated to poorly differentiated. They may demonstrate foamy cytoplasm or a vesicular nucleus due to the presence of lipid. Other tumors may demonstrate cells with hyperchromatic nuclei. In order to stain for intracellular lipid, tissue that has not been processed into paraffin is necessary. Frozen sections can then be prepared with Oil red O or Sudan black stains to identify lipid. Also typical of sebaceous adenocarcinoma is pagetoid spread (clusters of tumor cells within the epidermis that have no apparent connection to the main portion of the tumor). Tumors may also spread in an in situ fashion, replacing normal epidermis and without dermal invasion.

Muir Torre syndrome (a subset of Lynch syndrome) is a rare autosomal dominant condition that predisposes to keratoacanthoma, basal cell carcinoma, sebaceous gland carcinoma and internal malignancies such as colon and genitourinary malignancies [8]

MCC is a rare but aggressive malignancy that typically affects older individuals with significant UV light exposure. Early histological studies suggest that MCC arises from Merkel cells, mechanoreceptor cells responsible for tactile sensation, located in the basal epidermis. Alternatively, it is also hypothesized that these tumors originate from immature totipotent stem cells of the skin. Risk factors for MCC include UV exposure, fair skin, age, immunosuppression, and infection with Merkel cell polyomavirus. [9]

The typical presentation of MCC is a pink to blue-red, rapidly growing, painless, firm, shiny nodule with intact overlying skin. It is most frequently located on the upper eyelid, head, or neck and is often misdiagnosed as a cyst, lipoma, or other benign lesion. Because of their subtle yet aggressive nature, up to 30% of patients have regional lymph node involvement at presentation. [10 ,11]

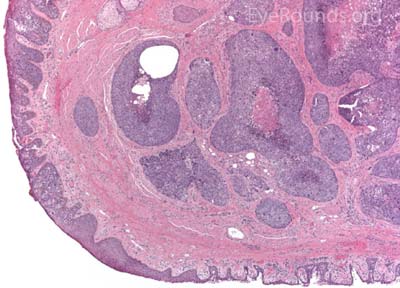

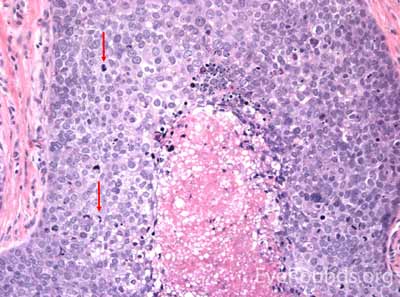

This neuroendocrine carcinoma is composed of deeply basophilic uniform cells with a high nucleus to cytoplasmic ratio, finely dispersed nuclear chromatin, and an inconspicuous nucleolus. Cells are crowded and often mold together. Single-cell necrosis, numerous mitotic figures, and lymphovascular, perineural, or epidermal invasion may also be seen. Merkel cells have features of both epithelial and neuroendocrine cells and express many markers that can be analyzed with immunohistochemistry such as synaptophysin, chromogranin and neurofilament.

The risk of MCC is higher in patients with other malignancies and those who are immunosuppressed. The diagnosis of MCC alone should raise suspicion for the presence of underlying multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, or malignant melanoma. Local recurrence and lymph node metastases are common; the 5 year survival is poor at 38%. [12]

Kanski JJ, Nischal KK, Bowling B. Clinical ophthalmology : a systematic approach. 7th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier/Saunders, 2011.

Lenci LT, Sciegienka S, Kirkpatrick CA, Clark TJ, Syed NA, Shriver EM. Malignant Lesions of the External Periocular Tissues Tutorial. EyeRounds.org. posted May 10, 2017; Available from: https://eyerounds.org/tutorials/malignant-lesions-of-ext-periocular-tissues/index.htm