Progressive central vision loss in both eyes

A 30-year-old woman presented for evaluation of vision loss in both eyes (OU) in the setting of a newly diagnosed transverse venous sinus thrombosis. Prior to the onset of her ocular symptoms, she had several weeks of sinus fullness and drainage and was prescribed montelukast (Singulair) and oral prednisone. Several hours after starting Montelukast, she experienced anaphylaxis with a diffuse urticarial rash, throat swelling, and difficulty breathing. She presented to her local emergency room and was given intravenous diphenhydramine and epinephrine. While receiving epinephrine, she developed a severe headache and 15 minutes later developed central vision changes OU, which progressed to complete central vision loss OU. She was sent to University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics (UIHC) the same day for further evaluation. A brain MRI was performed, which showed a left transverse venous sinus thrombosis (VST). Given the VST with headache and vision changes, there was concern for raised intracranial pressure. She was started on oral acetazolamide and admitted to the neurology service.

Recent fevers, otherwise negative except for what is detailed in the history of present illness

|

|

Figure 1. Pseudocolor fundus photos OD (left image) and OS (right image) three days after initial presentation. There were central petalloid lesions with blunted foveal reflexes OU.

|

|

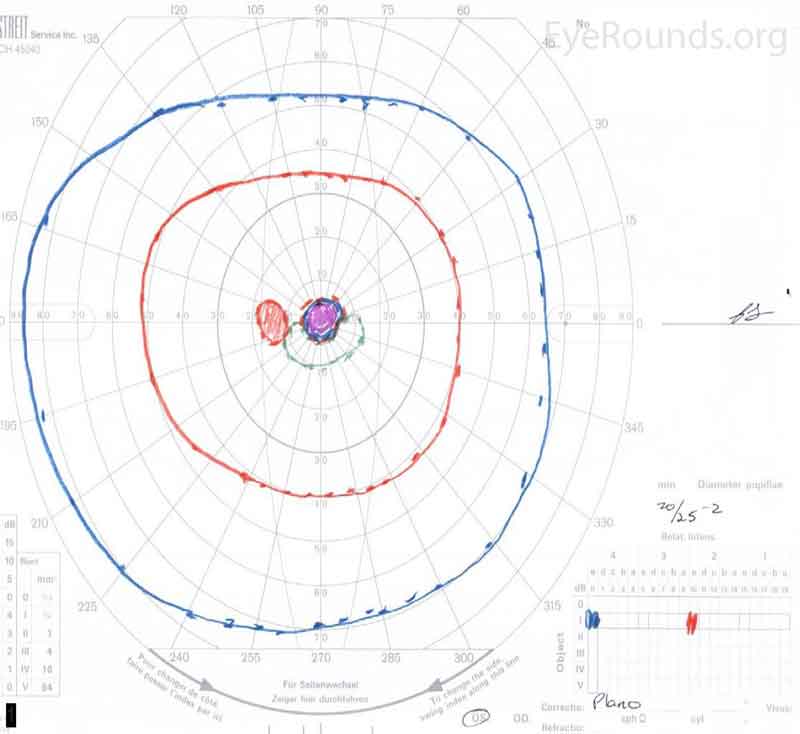

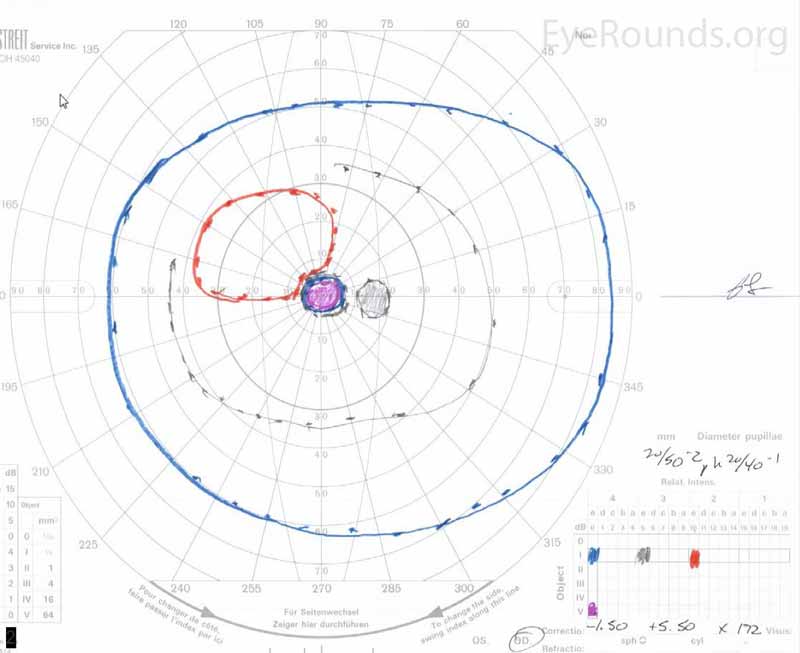

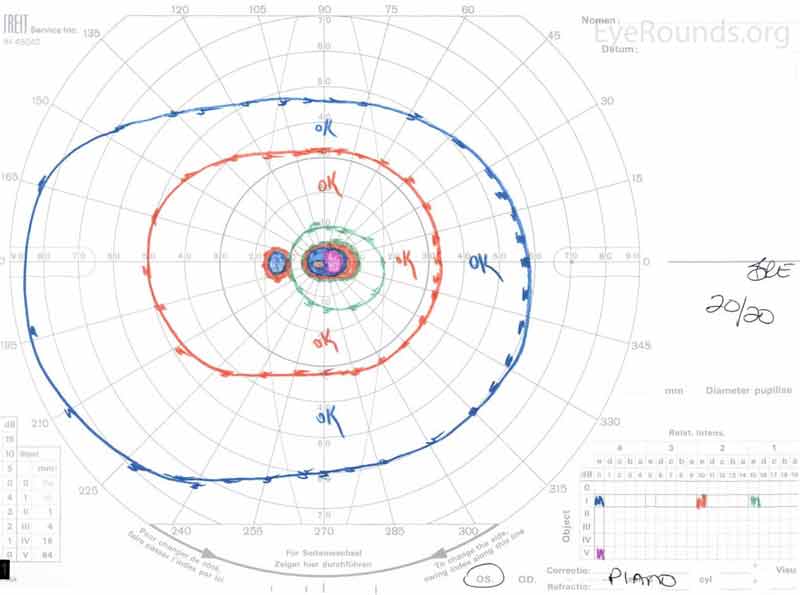

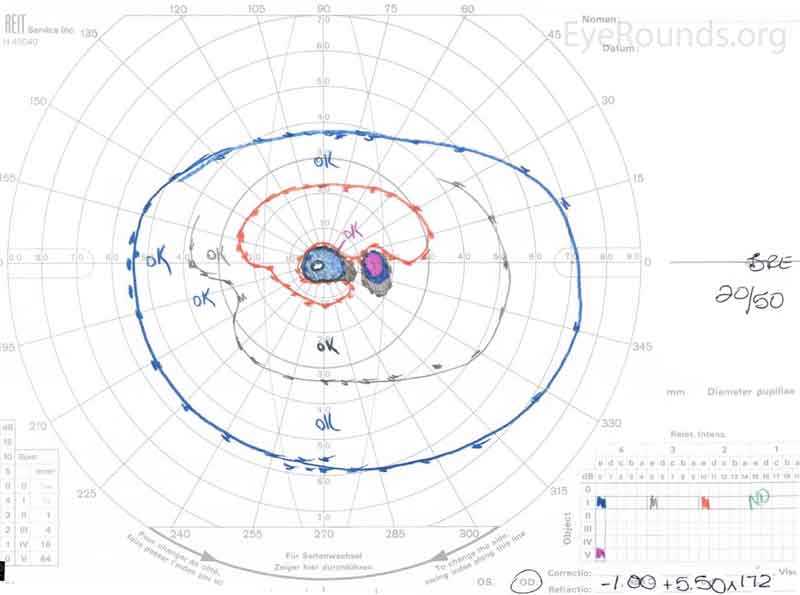

Figure 2. Goldmann Visual Fields (GVF) OU three days after initial presentation. There was a five-degree central scotoma to the V4e isopter OU. The I2e isopter was also constricted with complete loss of the I1e isopter OD (right image). There was superior constriction of the I1e isopter OS (left image).

|

|

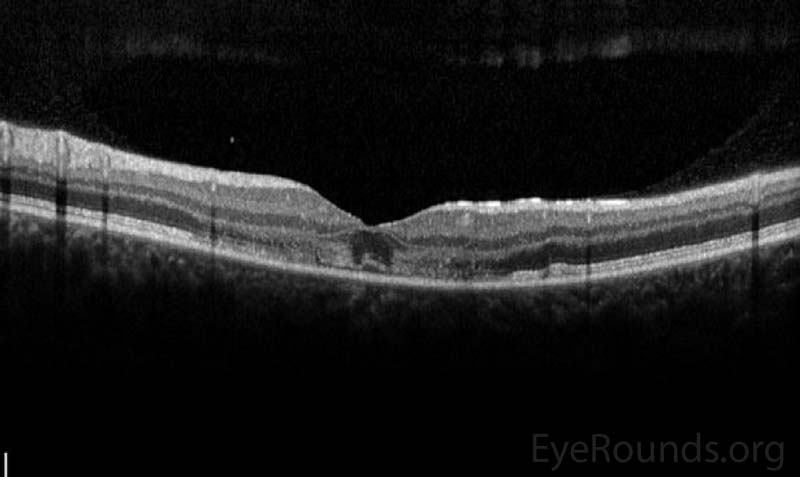

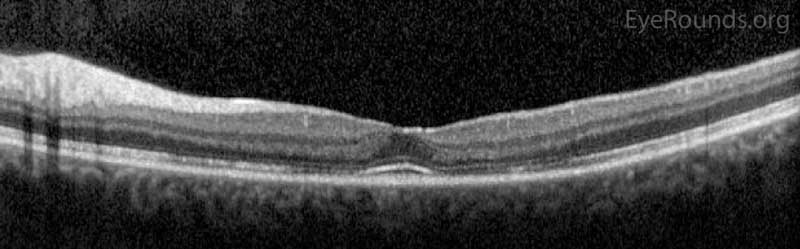

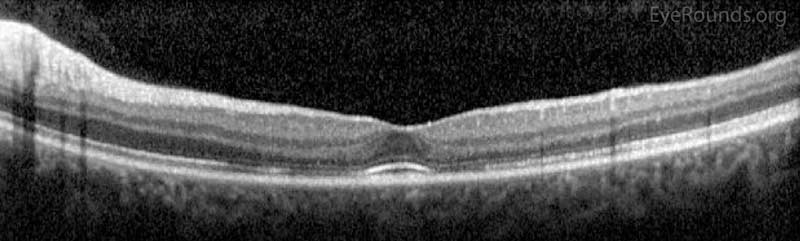

Figure 3. Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) of OD (upper image) and OS (lower image) three days after initial presentation. In both eyes, there was a parafoveal band of hyperintensity in the outer nuclear layer, outer plexiform layer and inner photoreceptor segments/outer photoreceptor segments junction. There was disruption of the inner segment/outer segment junction subfoveally OU.

|

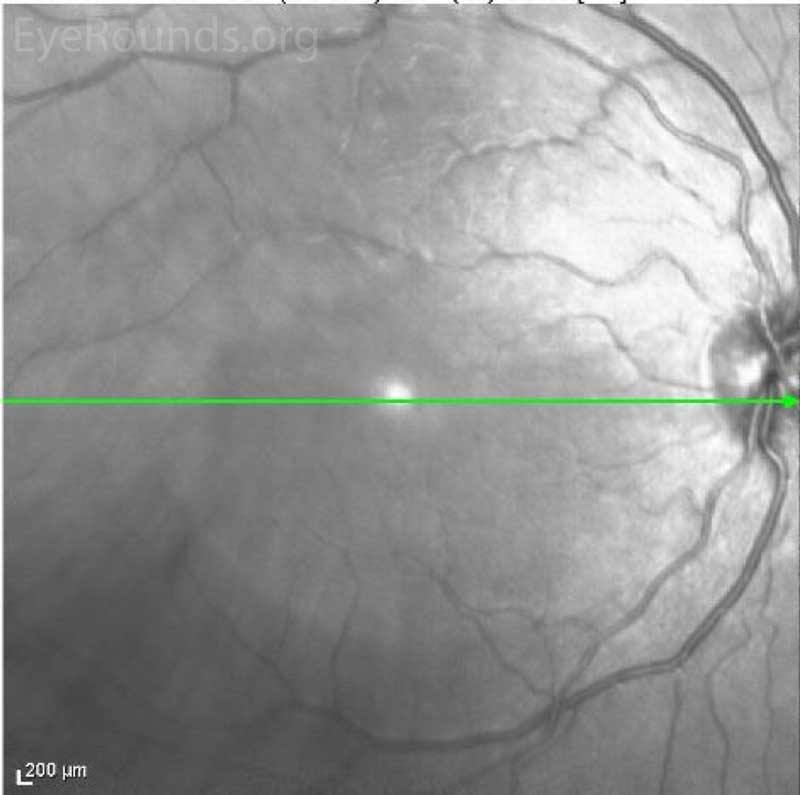

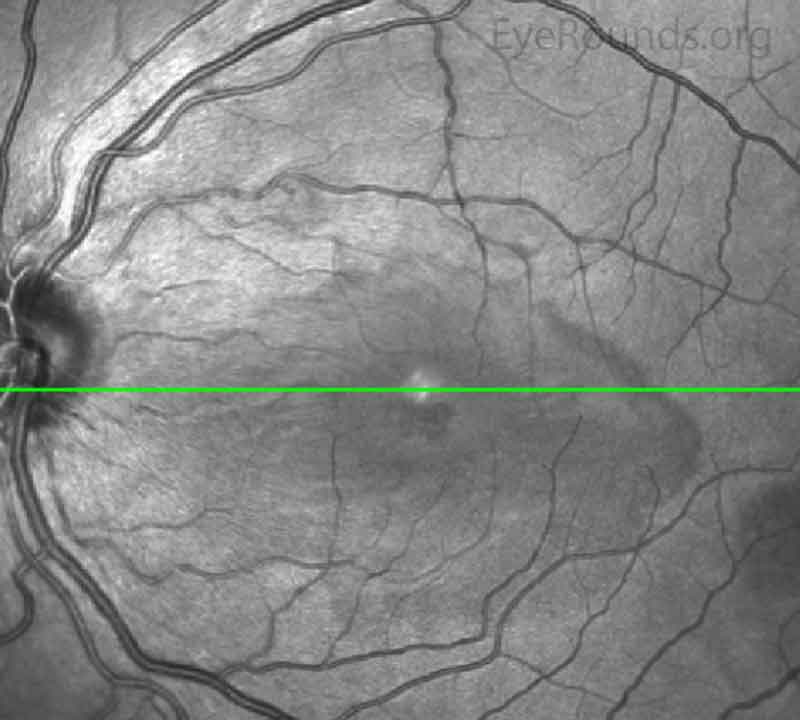

Figure 4. Near Infrared Image of OD (upper image) and OS (lower image) three days after initial presentation. In both eyes, there was a well demarcated hyporeflective petalloid lesion in the macula.

The patient was evaluated in the eye clinic three days after her initial onset of symptoms. Initially, given her symptoms of bilateral acute vision loss, there was concern for possible bilateral occipital stroke, toxic or infectious neuropathy, or possible chiasmal lesion. After an inpatient neurological evaluation with brain imaging, these etiologies were ruled out. As stated above, her imaging did show a venous sinus thrombosis. She also underwent a thorough ophthalmic evaluation that was consistent with the diagnosis of Acute Macular Neuroretinopathy (AMN). Given the lack of papilledema and other signs of raised intracranial pressure (ICP) in the setting of VST, acetazolamide was discontinued. She was observed without ophthalmic intervention. She was started on warfarin anticoagulation for the VST and had a work-up for hypercoagulable states, which was negative.

Her visual acuity improved rapidly to 20/50 OD and 20/20 OS without correction, which was her baseline acuity given her keratoconus. This remained stable for the next several months. GVF showed slight improvement of her bilateral paracentral scotomas (Figure 5), and OCT showed re-establishment of inner segment/outer segment junction in the subfoveal area OU (Figure 6).

|

|

Figure 5. Goldmann Visual Fields (GVF) OU two months after initial presentation. There was slight improvement of the patient's bilateral central scotomas.

|

|

Figure 6. Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) OD (upper image) and OS (lower image) two months after initial presentation. There was parafoveal thinning of the outer retina OU, but there was re-establishment of the inner segment/outer segment junction subfoveally OU.

Acute Macular Neuroretinopathy (AMN)

Acute Macular Neuroretinopathy (AMN) is a rare condition that was first described in 1975 by Bos and Duetman as a brownish-red wedge shaped petalloid macular lesion around the fovea with corresponding paracentral scotomas [1]. It can be somewhat variable in presentation, and given its rarity, it may be misdiagnosed as an infectious or inflammatory retinopathy. In AMN, however, the retinal vessels and optic nerve are unaffected, and AMN lesions typically resolve over several weeks to months with corresponding visual recovery [2]. Additionally, these macular lesions are often associated with recent viral-like illness, oral contraceptive use, or exposure to sympathomimetics [3]. The patient in this case report represents a classic history of AMN with multiple risk factors, including recent febrile illness, oral contraceptive use, and the use of epinephrine.

While the exact mechanism and etiology of AMN is unknown, microvascular ischemia of the choriocapillaris is a leading theory [4]. The choriocapillaris is a rich vascular bed in a honeycomb configuration with a central arteriole and surrounding draining venules [4]. The characteristic findings on retinal imaging (see Imaging below) correspond well to the distributions of the choriocapillaris. Multilobular AMN lesions suggest involvement of multiple, adjacent choroidal lobules [4]. A leading theory for the cause of ischemia is vasoconstriction provoked by catecholamine release following trauma or sympathomimetic use [3]. The choriocapillaris is thought to be susceptible to transient ischemic insult due to its relative lack of autoregulation and the presence of α-adrenergic receptors that may make this vascular bed susceptible to sympathetic stimuli [4]. It is hypothesized that the decreased flow in choriocapillaris is followed by hypoxic insult to the middle retina and then the outer retina [4]. AMN lesions often occur between the outer nuclear layer (ONL) and outer plexiform layer (OPL) and frequently involve the inner segment/outer segment junction and interdigitation zone [3]. Other mechanisms of ischemia include hyperviscosity from leukocytosis, increased capillary permeability, endothelial dysfunction and coagulopathy, platelet destruction, immune complex deposition, and consumptive coagulopathy [3].

AMN has been linked closely with another disease entity known as Paracentral Acute Middle Maculopathy (PAMM). These two conditions share some similarities; both AMN and PAMM present with paracentral scotomas and paracentral macular lesions with plaque or band-like hyperintense lesions on OCT, and both are thought to be due to ischemic events [3, 5, 6]. PAMM, however, is thought to be an occlusive disease of the superficial capillary plexus and/or deep capillary plexus resulting in ischemia of the INL and OPL [4]. Therefore, in PAMM, there is a hyper-intense band in the INL and OPL initially, followed by atrophy of the INL. These two entities also have demographic differences; PAMM most often occurs in older men with vasculopathic risk factors, while AMN more often occurs in younger women [5]. Further research is needed to better understand these disease entities and to develop therapeutics.

A comprehensive review of 101 AMN cases across 13 countries demonstrated that a majority of these patients were women with a M:F ratio of 0.16:1; the initial presentation most often occurred around the third decade of life [3]. Race was only documented in 35 of the 101 cases with 80% being non-Latino Caucasian [3]. Common exposures or risk factors have been identified, including oral contraceptive use, caffeine, and vasoconstrictive substances, such as epinephrine [2, 3, 7].

AMN typically presents with an acute central or paracentral scotoma, decreased vision, and/or blurred vision [3]. The central scotomas correspond with the petalloid macular lesions. These lesions often develop rapidly but occasionally can take up to several weeks to present [8]. The lesions and vision changes can be unilateral or bilateral [3, 7]. Visual acuity in most of these patients is generally preserved with over 80% of patients presenting with greater than 20/40 vision [3]. The most common finding on fundoscopy is the bilateral parafoveal wedge shaped reddish brown or orange color lesions, but it may also be petalloid, teardrop, or horseshoe shaped [3, 8].

En face near infrared (NIR) imaging shows characteristic teardrop, multilobular, or confluent multilobular lesions and is a sensitive imaging technique for AMN [3, 4, 7]. Spectral-domain structural OCT shows OPL, ONL, and Henle's layer hyperintensity, in addition to disruption of the interdigitation zone, inner segment/outer segment junction, and external limiting membrane [7, 9]. A study by Lee, et al. showed that OCT angiography (OCTA) identifies an inner choroidal flow void that corresponds to the regions of abnormal hyperreflectance of the outer retinal layers on OCT and the areas of hyporeflectance on NIR [4]. Although the deep capillary plexus perfuses the vulnerable watershed zone between the retinal and choroidal circulations, AMN patients do not have visible flow abnormalities within the deep capillary plexus by OCTA [4]. The areas of choroidal flow void on OCTA have been shown to persist, whereas the retinal hyperreflectance on spectral-domain OCT usually improve [4]. Multifocal electroretinography (mfERG) may also show reduced amplitudes corresponding to the retinal lesions [9]. Later signs may show thinning of the ONL and OPL [7]. Fluorescein angiogram is normal in this condition and can be useful to assist with ruling out other diagnoses like the white dot syndromes.

Currently, there are no agreed upon interventions or treatments for patients with AMN. There is a case report of visual and anatomical improvement of the scotomas with systemic corticosteroids; however, most patients are simply observed with gradual improved, but persistent, scotomas [3, 10].

EPIDEMIOLOGY OR ETIOLOGY (3)

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS (3)

|

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

|

Frisbie RA, Warren AK, Risma TBS, Abramoff MD. Acute Macular Neuroretinopathy. EyeRounds.org. April 1, 2019. Available from https://eyerounds.org/cases/285-Acute-Macular-Neuroretinopathy.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.